Renowned researcher offers insights on evolution at second Sparkuhl Lecture

Famed evolutionary biologist, Richard Lenski, was recently at McMaster to share insights from his groundbreaking long-term evolution experiment that followed populations of E.Coli bacteria as they evolved over 67,000 generations.

BY Erica Balch

September 29, 2017

When Charles Darwin first published On the Origin of Species in 1859, it was thought that the process of evolution occurred too slowly to be observed – that short of owning a time machine, it wouldn’t be possible to actually witness evolution, at least not in real time.

But for the past 30 years, renowned evolutionary biologist Richard Lenski has been watching evolution as it happens. In his groundbreaking E.coli Long-term Evolution Experiment project, Lenski has followed populations of E. coli bacteria as they evolved in the laboratory over 67,000 generations – four times more than the number of generations modern humans have existed.

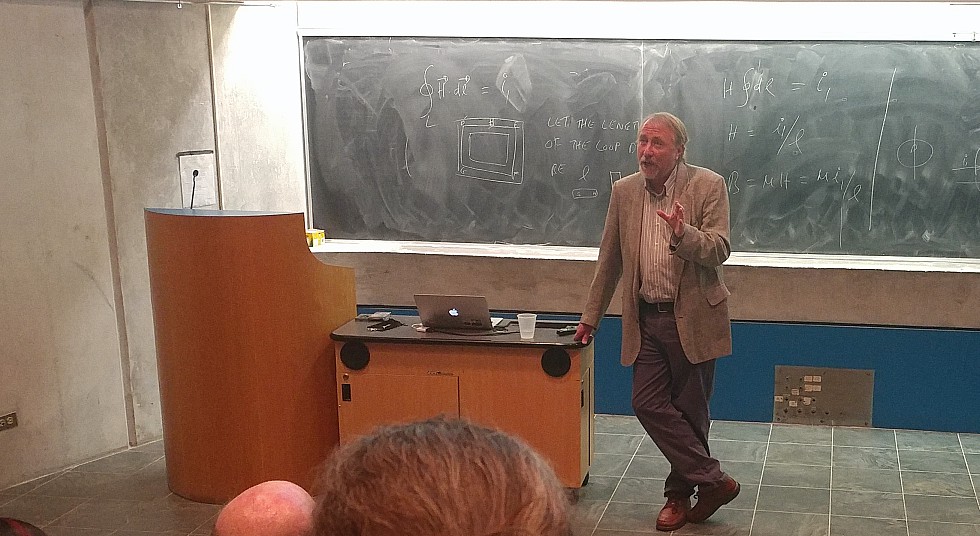

Lenski, the John Hannah Distinguished Professor of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics at the University of Michigan, was recently at McMaster to deliver the second Dr. Joachim Sparkuhl Lectureship in Biology in which Lenski shared insights from his landmark experiment.

“If we can see the process of evolution in action, we can see adaptation by natural selection, we can study and enjoy this tension between the predictability and repeatability of evolution and the divergence of forms of life,” says Lenski who spoke to more than 150 McMaster students, faculty and guests. “We can even see new functions emerging – not just organisms getting better at what they already do, but in some cases, developing unexpectedly new functions.”

Lenski began his experiment in 1988 with 12 populations of E. coli, all from the same strain and all living in the same mixture of glucose and citrate to study how similarly or differently each strain would evolve. He not only observed natural selection and the process of mutation at work, but found that after 30,000 generations of evolution, one of the strains developed the ability to eat citrate, something E.Coli aren’t supposed to be able to do.

As part of the experiment, which is ongoing, Lenski also freezes samples of the bacteria, creating a fossil record to understand how and why transitions may have ocurred. He can even bring frozen E.Coli back to life to compare and compete ancestral samples with newer generations to see if earlier samples evolve in the same way.

Ian Dworkin, an assistant professor in McMaster’s Department of Biology and organizer of the talk, gave introductory remarks and spoke about the rich contribution Lenski has made to expanding scientific understanding of evolution.

“Rich had a great idea – he asked, how much would things change if you really kept going? How much evolution would you see? What would you see?” says Dworkin. “Even though he’s looking at this really simple microbe, he – along with the students and post-docs he has worked with and mentored – has answered these questions and fundamentally changed the way we think about evolutionary biology.”

During the lecture, Lenski also spoke about two additional research projects; one on the co-evolution of bacteria and the viruses that infect bacteria, the other on the evolution of non-living systems – in this case, artificial life in the form of computer programs.

The Sparkuhl lecture series was established in memory of scientist, philosopher and teacher, Dr. Joachim Sparkuhl, a biologist who had a life-long passion for learning, and spent his life exploring the implications of science and the scientific method on human knowledge.

Along with the lecture, Dr. Sparkuhl’s fund also provides a summer research scholarship in biology – the Dr. Joachim Sparkuhl Undergraduate Research Award in Genomics, Genetics & other Biological Sciences – an endowment created to honour his commitment to research integrity, to advance the study of biology and to support original research.