Rethinking the penalties for rape

Activists protest in Barcelona, Spain on June 21, 2018. A Spanish court triggered a new wave of outrage by granting bail to five men acquitted of gang rape and convicted instead on a lesser felony of sexual abuse, a case that has shocked Spain. (AP photo/Emilio Morinatti)

BY Lucia Lorenzi

July 12, 2018

The past few years have seen intense bouts of media coverage of high profile sexual assault and harassment cases. However, the #MeToo movement has achieved the kind of momentum and longevity that has rarely been seen.

In addition to survivors telling their stories, there are discussions and debates that are often extremely heated. Two big questions seem to come up time and again. What exactly does sexual assault and harassment look like? What are the appropriate punishments for acts of sexual violence and who gets to decide what they will be?

Germaine Greer weighs in

(Germaine Greer.

Shutterstock)

Recently, feminist writer and scholar Germaine Greer weighed in on how we should deal with sexual assault. In a speech at the Hay Festival, an annual literary festival in Wales, Greer argued that rape is not a “spectacularly violent crime.” She said that most rapes are just “lazy, careless and insensitive” incidents of “bad sex.” Greer’s full argument on rape will be published in a new book, coming out in Australia in September.

Greer, who is a survivor of a violent rape, argued that the statistics on post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and sexual violence are likely grossly inflated. In her view, society seems to condition women to believe that sexual assault is capable of destroying their lives.

Greer advocated for punishments for rape to be reduced. She suggested that sentencing might include 200 hours of community service, or a large tattoo of the letter R (for rapist) on the offender’s hand, arm or cheek.

Understandably, Greer’s comments provoked a swift backlash.

Laura Bates, a former actor who founded the #EverydaySexism project in 2012, argued that further diminishing the severity of rape is dangerous at a moment when the impact of sexual violence is finally being discussed. She said we should not abandon trying rape cases simply because they are difficult to prosecute.

PTSD and trauma from rape

Greer’s commentary is dangerous because it denies the evidence regarding PTSD related to sexual violence. A 2017 study published in the European Journal of Psychotraumatology examined data from the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Surveys.

It showed that interpersonal trauma was linked to the highest risk of developing PTSD. Those who experienced traumatic experiences within the broad category of intimate partner sexual violence accounted for the highest population burden of PTSD.

PTSD is a clinical diagnosis of trauma, and not the only way that we measure how survivors are impacted by assault. Unfortunately, our cultural understanding of trauma often aligns with the strict diagnostic criteria of PTSD. There are certain key features of the clinical diagnosis that we might popularly associate with “real” trauma: trouble remembering details, hypervigilance, an avoidance of triggers.

However, as researchers point out in a 2018 review of the diagnostic criteria of PTSD, “exposure to trauma is not tantamount to a diagnosis of PTSD, as most trauma exposures do not result in PTSD.” The absence of PTSD after a rape, however, is not the absence of trauma. It does not mean that an individual’s life might not be profoundly impacted by an experience of sexual violence.

When Greer doubts that rape can destroy someone’s life, she denies others’ experiences rather than providing a helpful observation that rape doesn’t affect everyone in the same way. She fails to address that trauma and PTSD are not the same thing, and shows we desperately need a robust understanding of trauma and how it encompasses a wide variety of experiences.

A long history of restorative justice

Because she claims to have had minimal trauma from her own rape — and that most rapes are the result of inconsiderateness rather than violence — Greer infers that punishments need not be so severe. What Greer seems to forget is that feminist activists and legal scholars alike have long been rethinking how to best address sexual violence.

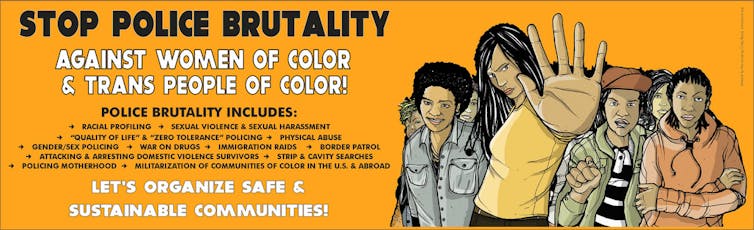

Racialized activists, such as those with INCITE!, a network of feminists working to end violence against women, gender non-conforming and trans people of colour,, have long histories of seeking alternative solutions to the criminal justice system, particularly because of how people of colour are disproportionately impacted by incarceration.

Artwork by Cristy C. Road/INCITE)

Criminal justice provides a blanket solution: Jail time. The primary variable one has to consider is how much time is to be served: none, a lot or something in between.

If we are to consider other solutions, including those found in restorative justice programs, then it is possible that 200 hours of community service could be an appropriate punishment for a particular incident of sexual assault. Indigenous communities especially have been at the forefront of this work, as can be seen in initiatives such as the Vancouver Aboriginal Transformative Justice Service Program.

Better conversations needed

It will take time for us to respond differently to violence. It takes a willingness to recognize that sexual assault has a wide range of impacts on victims, and that it is impossible to universalise the experience. As professor Anita Hill told Daphne Branham of the Vancouver Sun, “It is a long time coming and not going to happen overnight… But we are at a moment where there is resolve on the part of many people. If ever it could be possible, now is that time.”

We often make broad statements or claims about sexual violence to be strategic; to raise awareness, to show solidarity or to demonstrate the scope of the problem. #MeToo owes a great deal of its success to its wide reach and broad scope. It is also easy for individual personal experience, like Greer’s to become the basis of larger claims to truth, especially at the expense of others.

![]() Greer’s comments have added troubling fuel to the fire of debate. Hopefully, they can also reignite more productive, respectful and evidence-based conversations about the complexities of violence.

Greer’s comments have added troubling fuel to the fire of debate. Hopefully, they can also reignite more productive, respectful and evidence-based conversations about the complexities of violence.

Lucia Lorenzi, SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow in English and Cultural Studies, McMaster University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.