Do truth and reconciliation commissions heal divided nations?

In this October 1998 photo, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu dance after Tutu handed over the final report of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Pretoria. (AP Photo/Zoe Selsky)

BY Bonny Ibhawoh

January 24, 2019

Bonny Ibhawoh, McMaster University

As long as unresolved historic injustices continue to fester in the world, there will be a demand for truth commissions.

Unfortunately, there is no end to the need.

The goal of a truth commission — in some forms also called a truth and reconciliation commission, as it is in Canada — is to hold public hearings to establish the scale and impact of a past injustice, typically involving wide-scale human rights abuses, and make it part of the permanent, unassailable public record. Truth commissions also officially recognize victims and perpetrators in an effort to move beyond the painful past.

Over the past three decades, more than 40 countries have, like Canada, established truth commissions, including Chile, Ecuador, Ghana, Guatemala, Kenya, Liberia, Morocco, Philippines, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa and South Korea. The hope has been that restorative justice would provide greater healing than the retributive justice modelled most memorably by the Nuremberg Trials after the Second World War.

There has been a range in the effectiveness of commissions designed to resolve injustices in African and Latin American countries, typically held as those countries made transitions from civil war, colonialism or authoritarian rule.

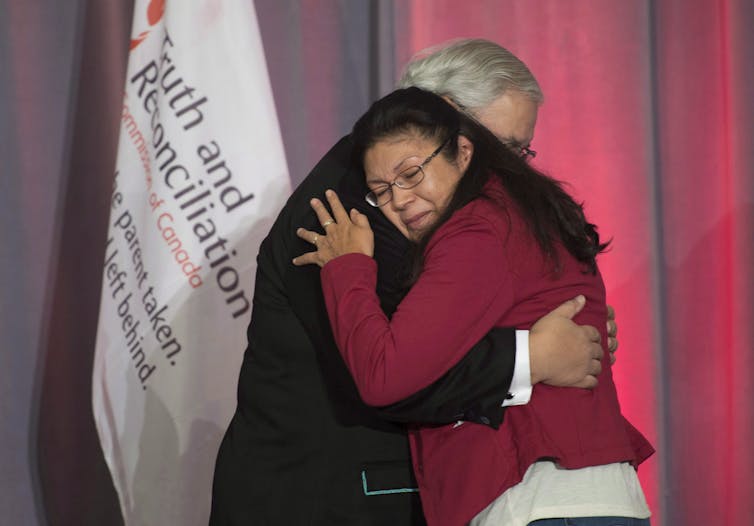

Most recently, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission addressed historic injustices perpetrated against Canada’s Indigenous peoples through forced assimilation and other abuses.

Its effectiveness is still being measured, with a list of 94 calls to action waiting to be fully implemented. But Canada’s experience appears to have been at least productive enough to inspire Australia and New Zealand to come to terms with their own treatment of Indigenous peoples by exploring similar processes.

Although both countries have a long history to trying to reconcile with native peoples, recent discussions have leaned toward a Canadian-style TRC model.

South Africa set the standard

There had been other truth commissions in the 1980s and early 1990s, including Chilé’s post-Pinochet reckoning.

But the most recognizable standard became South Africa’s, when President Nelson Mandela mandated a painful and necessary Truth and Reconciliation Commission to resolve the scornful legacy of apartheid, the racist and repressive policy that had driven the African National Congress, including Mandela, to fight for reform. Their efforts resulted in widespread violence and Mandela’s own 27-year imprisonment.

Through South Africa’s publicly televised TRC proceedings, white perpetrators were required to come face-to-face with the Black families they had victimized physically, socially and economically.

Source: Facing History and Ourselves.

There were critics, to be sure, on both sides. Some called it the “Kleenex Commission” for the emotional hearings they saw as going easy on some perpetrators who were granted amnesty after demonstrating public contrition.

Others felt it fell short of its promise — benefiting the new government by legitimizing Mandela’s ANC and letting perpetrators off the hook by allowing so many go without punishment, and failing victims who never saw adequate compensation or true justice.

These criticisms were valid, yet the process did succeed in its most fundamental responsibility — it pulled the country safely into a modern, democratic era.

Saving humanity from ‘hell’

Dag Hammarskjöld, the secretary general of the United Nations through most of the 1950s who faced criticism about the limitations of the UN, once said the UN was “not created to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell.”

Similarly, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission was not designed to take South Africa to some idyllic utopia. After a century of colonialism and apartheid, that would not have been realistic. It was designed to save South Africa, then a nuclear power, from an implosion — one that many feared would trigger a wider international war.

To the extent that the commission saved South Africa from hell, I think it was successful. Is it a low benchmark? Perhaps, but it did its work.

Since then, other truth commissions, whether they have included reconciliation or reparation mandates, have generated varying results.

Some have been used cynically as tools for governments to legitimize themselves by pretending they have dealt with painful history when they have only kicked the can down the road.

In Liberia, where I worked with a team of researchers last summer, the records of that country’s truth and reconciliation commission are not even readily available to the public. That secrecy robs Liberia of what should be the most essential benefit of confronting past injustices: permanent, public memorialization that inoculates the future against the mistakes of the past.

U.S. needs truth commission

On balance, the truth commission stands as an important tool that can and should be used around the world.

It’s painfully apparent that the United States needs a national truth commission of some kind to address hundreds of years of injustice suffered by Black Americans. There, centuries of enslavement, state-sponsored racism, denial of civil rights and ongoing economic and social disparity have yet to be addressed.Like many, I don’t hold out hope that a U.S. commission will be established any time soon – especially not under the current administration. But I do think one is inevitable at some point, better sooner than later.

Wherever there is an ugly, unresolved injustice pulling at the fabric of a society, there is an opportunity to haul it out in public and deal with it through a truth commission.

Still, there is not yet any central body or facility that researchers, political leaders or other advocates can turn to for guidance, information and evidence. Such an entity would help them understand and compare how past commissions have worked — or failed to work — and create better outcomes for future commissions.

As the movement to expose, understand and resolve historical injustices grows, it would seem that Canada, a stable democracy with its own sorrowed history and its interest in global human rights, would make an excellent place to establish such a centre.![]()

Bonny Ibhawoh, Professor of History and Global Human Rights, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.