McMaster researchers use friendly viruses to make a gel that can heal itself – and you

Photo by JD Howell.

BY Wade Hemsworth

July 25, 2019

McMaster researchers have developed a novel new gel made entirely from bacteria-killing viruses.

The anti-bacterial gel, which can be targeted to attack specific forms of bacteria, holds promise for numerous beneficial applications in medicine and environmental protection.

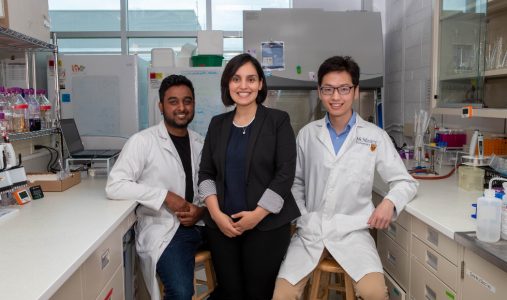

Among many possibilities, it could be used as an antibacterial coating for implants and artificial joints, as a sterile growth scaffold for human tissue, or in environmental cleanup operations, says chemical engineer Zeinab Hosseini-Doust.

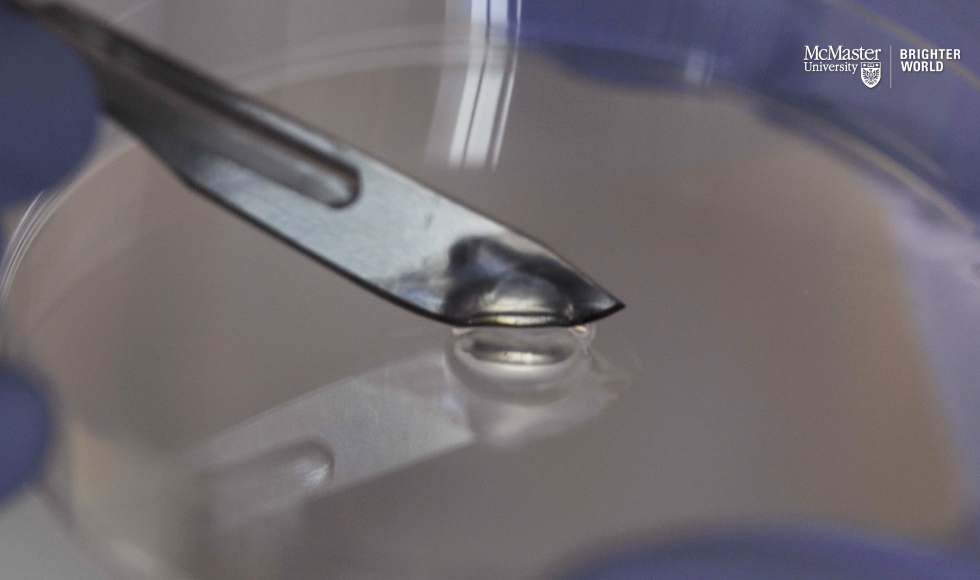

Her lab, which specializes in developing engineering solutions for infectious disease, grew, extracted and packed together so many of the viruses – called bacteriophages, or simply phages – that they assembled themselves spontaneously into liquid crystals and, with the help of a chemical binder, formed into a gelatin-like substance that can heal itself when cut.

Yellow in colour and resembling Jell-O, a single millilitre of the antibacterial gel contains 300 trillion phages, which are the most numerous organisms on Earth, outnumbering all other organisms combined, including bacteria.

“Phages are all around us, including inside our bodies,” explains Hosseini-Doust. “Phages are bacteria’s natural predators. Wherever there are bacteria, there are phages. What is unique here is the concentration we were able to achieve in the lab, to create a solid material.”

The field of phage research is growing rapidly, especially as the threat of antimicrobial resistance grows.

“We need new ways to kill bacteria, and bacteriophages are one of the promising alternatives,” says Lei Tian, a PhD student in Hosseini-Doust’s lab and a co-author on the paper describing the research, published today in the journal Chemistry of Materials. “Phages can kill bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics.”

Hosseini-Doust says the DNA of phages can readily be modified to target specific cells, including cancer cells. Through a Nobel Prize-winning technology called phage display, it’s even possible to find phages that target plastics or environmental pollutants.

Being able to shape phages into solid form opens new vistas of possibility, just as their utility in fighting diseases is being realized, she says.

Recently, the story was highlighted in stories on CTV and CBC.