Understanding the origins of celiac and irritable bowel diseases

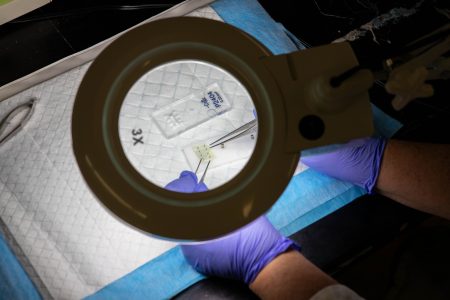

Elena Verdú in the Axenic Gnotobiotic Unit in the Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute. Photo by Georgia Kirkos.

BY Tina Depko, Health Sciences

October 17, 2019

Elena Verdú has numerous titles, publications, grants and honours to her name.

She holds the Canada Research Chair in Nutrition, Inflammation and Microbiota. She is a professor in the Department of Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at McMaster University. She is the director of the Axenic Gnotobiotic Unit in the Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute, and she oversees her own lab.

Verdú has publications in renowned journals, such as Nature Communications and Gastroenterology.

While a few of her achievements would make any researcher proud, Verdú says they are not what matter most to her.

“I always tell my students and postdocs that it is good to have ambitious goals, but don’t let those goals blind you from making the most of the present,” she said. “It is not about the destination. It’s about the process and the learning that takes place that matters.”

The Verdú lab at McMaster’s internationally renowned Farncombe Institute investigates host-microbial and dietary interactions in the gastrointestinal tract as it relates to the development of celiac disease and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Up to 40 per cent of global populations have a genetic predisposition to celiac disease, but only one per cent develops the autoimmune condition when exposed to dietary gluten. Verdú’s research focuses on how this could be influenced by the type of bacteria present in the gut.

“We’re very interested in celiac disease as roughly 350,000 Canadians suffer from celiac disease, but most are undiagnosed because it is an understudied disease and awareness is quite low,” said Verdú.

“To have celiac disease, you need to have certain genes, and we know which genes those are. You also need the main environmental trigger, gluten, which are proteins in wheat, rye and barley. We know exactly how gluten interacts with the genes that provide risk for the disease. Since not all people who have the risk genes and eat gluten have the disease, this tells us there are additional unknown factors, and that’s what we’re focused on.”

Verdú’s lab studies gnotobiotic mouse model colonization using bacteria isolated from both celiac disease and IBD patients to better understand the mechanisms underlying the link between bacterial communities and those diseases.

“As biomedical researchers we tend to have the goal – the cure, the cure, the cure. I think that this is a good long-term aim, but we should put realistic aims in there too,” Verdú said. “For me, the immediate goal is to discover new mechanisms of these diseases that can be targeted with new therapies, including drug development.”

David Armstrong, professor of medicine at McMaster and a consultant gastroenterologist at Hamilton Health Sciences, collaborates with Verdú on research initiatives. He says Verdú is recognized, nationally and internationally, as an expert in her field.

“Dr. Verdú and her team are producing groundbreaking research that is directly relevant to patients with digestive health issues, including celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease and functional bowel disorders,” he said. “She is one of those rare investigators who conducts outstanding basic research that is grounded in a very clear understanding of the clinical challenges faced by patients with gastrointestinal diseases.”

Verdú grew up in the bustling metropolis of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Her father was a rheumatologist and a professor of medicine at the university, while her mother was a nurse in a private practice. While Verdú was always drawn to the idea of research, she was motivated to approach this field armed with a medical degree.

“As a student in Argentina, I knew of several cases of medical doctors who had then gone on to perform Nobel Prize-winning research in basic science, and so I knew that a degree in medicine could be very useful to a later career in research,” she said.

Verdú received an MD degree and trained in internal medicine and gastroenterology at the University of Buenos Aires. She pursued clinical research training in gastroenterology at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland.

It was in Switzerland that she met a fellow gastroenterology trainee, Premysl Bercik. The two married and moved to Prague, where she completed a PhD in immunology and gnotobiology at the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague.

She and Bercik then undertook the daunting task of looking for an institution where they could both pursue their postdoctoral work.

“We started to think about where there was an all-star team in gastroenterology and that’s why we chose Dr. Stephen Collins’ lab in the Intestinal Diseases Research Program at McMaster, coming in 1998, before it became the Farncombe Institute,” she said. “We thought we would just come for our postdocs and return to Europe, but we stayed because of the learning and research environment.”

As Verdú’s career trajectory continues to rise, she strives to start others on the same arc. Trainees and postdoctoral fellows in her lab have gone on to research labs, medical schools and academic appointments around the world.

“We don’t do anything in isolation here, so everything is teamwork,” she said. “It is very important to me that each student or postdoc have their own projects, but that they also cross-pollinate between projects.”

Outside of the lab, Verdú and Bercik enjoy spending time with their two adult sons, Erik, an artist and video game designer, and Alex, who is pursuing a master’s/PhD degree in aerospace science and engineering.

While Verdú’s dad, Raúl, didn’t live long enough to see her career fully flourish, Verdú says he already knew in his heart where her journey would lead.

“My dad passed away before he saw me become a professor, but when I was a postdoc here, he was already telling everyone I was a professor at McMaster,” she said. “I’ll always remember that.”