Canada’s investments in health and training are too valuable to treat like paper clips

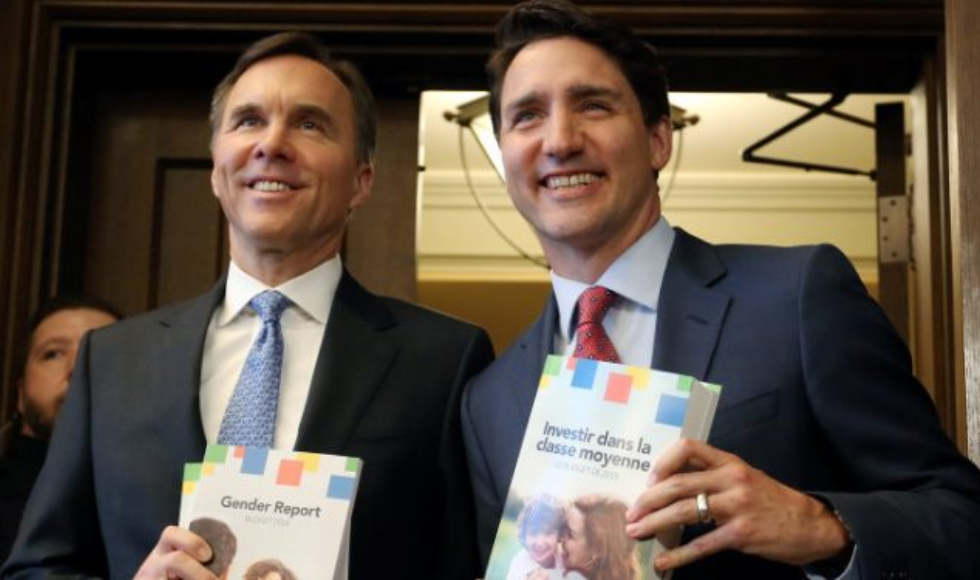

Finance Minister Bill Morneau and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, pictured with the 2019 federal budget last March. A lack of reporting around government investments in intangible assets can cloud the decision-making process and distort values and priorities, potentially leading to inefficiencies and missed opportunities, writes Jeremiah Hurley. Photo by Andrew Meade, The Hill Times.

BY Jeremiah Hurley, Dean Faculty of Social Sciences

November 7, 2019

This article originally appeared in The Hill Times.

Imagine you have to decide whether it’s worthwhile to fund a government program to provide early intervention for psychosis

The program is expensive. Setting it up requires establishing treatment protocols, organizing special teams and services, and a myriad of other costs. And the hospital-based treatment itself is costly. But consider the benefits: aside from saving lives and improving health, effective early treatment saves on health care, social, community, and criminal justice costs down the road, and recipients are able to work more and more productively.

Taking the whole picture into account, the early treatment program, though expensive, may actually be a bargain for society.

Investing in a program like this creates intangible assets for government and society: the capacity for government to deliver a valuable service, and “human capital” for the recipients—better health, improved skills, and enhanced social functioning.

The way that current rules account for public spending on such a program makes it difficult to compare its long-lasting social benefits to the benefits of spending on other needs.

Setting an entire tax-funded budget is already freighted with the push and pull of competing priorities, limited resources, and political realities. Finding the best balance is challenging, and it helps to make an accounting demarcation between capital and operating expenses.

When a government invests in a tangible asset, such as a highway or building, for example, the funding comes from a capital budget and the government is permitted to amortize the costs over the life of the asset and recognize the value of the new asset on its balance sheet.

By contrast, when a government invests in intangible assets, such as early psychosis treatment that generates benefits to society over many years, the costs are funded through the operating budget and the government is not allowed to recognize the intangible asset created, or to amortize its costs.

From an accounting, budgeting, and reporting perspective, such investments bear little distinction from spending on paper clips.

This different treatment can make investing in tangible assets seem more attractive than investing in health, social, and educational programs that produce intangible, but real assets for government and society.

This can cloud the decision-making process and distort values and priorities, potentially leading to inefficiencies and missed opportunities.

It doesn’t have to be this way, and in some places, it is already changing. In New Zealand, for example, the government already has a “well-being” budget process that identifies, prioritizes, and reports on investments in human capital.

Even the private sector is acting: publicly traded companies in the U.K. are now required to report on human capital, including investments in diversity, human resource development, and social and community issues.

In the U.S., the Securities and Exchange Commission is considering replacing the existing requirement that publicly traded companies disclose the number of employees with a requirement to disclose a description of the registrant’s human capital resources, including measures or objectives related to managing the business.

What can we do in Canada?

Here, the value created by such expenditures would never show up on a government balance sheet or be recognized through any formal reporting process, even though enhanced health, better performance, and higher capacity generate lasting benefits for Canadian individuals and society. And this, of course, is a primary purpose of government.

Some of this would be easy, such as changing requirements for key budget documents so they lay out, with supporting evidence, the long-term economic and social costs and benefits of such investments.

The harder part will be building institutional capacity to gather and present such evidence systematically, so it becomes a permanent and ongoing part of the budgeting, decision-making, and reporting processes of government.

Currently, the most important assets created by these investments—the enhanced human, health, and social capital created in Canadians and their communities—are not reported anywhere.

It’s time we got started.