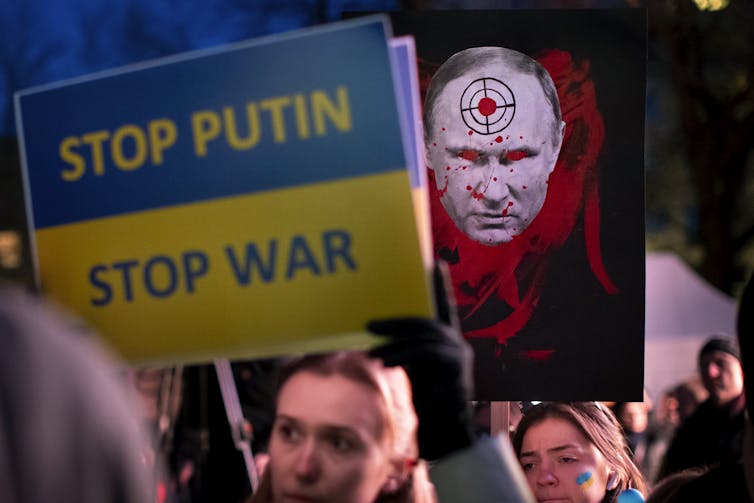

Analysis — Putin’s Ukraine invasion: Do declarations of war still exist?

A gym is in ruins following a shelling in Kyiv, Ukraine, on March 2, 2022. Russian forces have escalated their attacks on crowded cities in what Ukraine’s leader called a blatant campaign of terror. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky)

BY Rebekah K. Pullen and Catherine Frost

March 3, 2022

When Russian President Vladimir Putin announced in the early hours of Feb. 24, 2022, that Russia was beginning military action in Ukraine, he was echoing a tradition older than Russia itself. Throughout history, the practice of issuing statements announcing hostilities has marked the point where conventional politics ends and deadly conflict begins.

In ancient Rome, special priests were responsible for calling out at the enemy frontier that righteous war was imminent. Defeat meant their death.

In 1907, the Hague Convention on the laws of war formalized a long-standing practice when it specified that “hostilities should not commence” without prior warning and that “neutral powers” should be notified “without delay.”

The creation of the United Nations in 1945 was supposed to make the declaration of war obsolete and effectively outlaw war itself by creating the UN Security Council to address “use of force” questions between states. But it didn’t remove the right of states to independently initiate action under limited conditions of self-defence, set out in Sec. 7, Article 51 of the UN Charter.

War declarations are uncommon

While they are now exceedingly rare and few states have issued one since the Second World War — Canada, for example, first declared war on Germany in 1939 and last declared war on Japan in 1941 — such declarations weren’t entirely silenced.

Under international law, a declaration of war traditionally contained three ingredients: an announcement of the intention to take violent action, an explanation why and a proposal of what could prevent it.

As diplomatic instruments, declarations of war ensure a slender thread of communication continues between enemies, even under the worst conditions. And they prompt a final reflection on whether a state’s cause is just before events go too far.

Merely issuing a declaration is not sufficient to justify war, and some forms of warfare such as nuclear weapons or attacks on civilians cannot be justified. But used wisely, war declarations reflect an effort to reduce the likelihood, duration and intensity of violence. This may explain why the instinct to publicly justify lethal force has outlived empires.

Even when the reasons given are threadbare and unconvincing, the announcement alerts all who hear it to impending new danger.

‘Too late’ to avert the invasion

Putin’s Ukraine announcement came as the UN Security Council was holding a last-ditch meeting to avert conflict. Ukraine’s representative broke the news, calling the UN’s efforts “too late.” The Russian representative declined to wake the Russian foreign minister to confirm events.

Canadians with loved ones caught in the conflict woke to the news that events had turned dire. For those closer to the action in Kyiv, Putin’s announcement was quickly followed by explosions.

Putin’s warning included his belief that the security and values of Russia in the post-Cold War world order was under threat. It maintained that military action was necessary to protect the breakaway regions of Donetsk and Luhansk in eastern Ukraine from a Nazi-led “genocide.”

These claims are disputed by Canada, the United States and other western nations. Legal experts consider them a cynical sham.

False genocide claims

Ukraine has filed an urgent appeal with the International Court of Justice calling for an immediate halt to military operations on the grounds that false Russian genocide claims violate the Genocide Convention.

The International Criminal Court has also opened an investigation into war crimes resulting from the conflict.

In today’s international order, it’s no longer necessary to declare war for a war to exist. The 1949 Geneva Convention was designed to apply even without official declarations of war. But the long tradition of publicly airing grievances helped build an extensive record of international norms on how and why conflict might lawfully occur.

Understanding the origins of hostilities through these norms can help establish guardrails on a conflict, identify when it breaches global conventions and suggest how it might be resolved.

‘Special military operation’

Notably, Putin never formally declared war on Ukraine, calling the invasion a “special military operation.” He may have stopped short of a full declaration because under international law it’s a communique between sovereign states, a status he is keen to deny Ukraine.

But he did issue his statement in a public form and by citing Article 51 of the UN Charter and the right of self-determination under Article 1, he appealed to international law to justify Russia’s actions.

So long as the system of sovereign states continues, states will act of their own accord. With or without the UN, military action across national borders impacts states and individuals far beyond, making war everybody’s business.

A war doesn’t need a declaration to begin. And the practice has been misused throughout history, sometimes deliberately.

But the impulse to present a document or speech to the greater global community says something significant about how states regard the legitimacy of their sovereignty — and their place in the existing international order.![]()

Rebekah K. Pullen is a Phd candidate in international relations at McMaster University and Catherine Frost is a professor of political science at McMaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.