Analysis: The protests in Iran are part of a long history of women’s resistance

A placard with a picture of Mahsa Amini, whose death while being detained by Iran’s morality police has ignited a wave of protests across the country. (AP Photo/Markus Schreiber)

BY Niloofar Hooman

October 24, 2022

On Sept. 16, Mahsa (Zhina) Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman, died in Tehran while in the custody of Iran’s morality police. Her death set off a massive wave of demonstrations that have spread across the country.

While the protests started with anger over the enforcement of the hijab, they represent a much wider movement that now poses the greatest threat the theocratic regime has faced since the 1979 revolution.

Controlling women’s bodies

As initial news of Amini’s hospitalization spread, angry citizens began demonstrating against the morality police. This coercive force has compelled women to comply with the mandatory hijab law through physical and verbal violence and humiliation — all part of a systematic effort to suppress and control their bodies.

The first spark of the growing protest movement came when Kurdish women attending Amini’s funeral in her hometown of Saqqez bravely took off their headscarves and chanted the slogan “death to the dictator” at great risk to their own safety.

After Amini’s death, the outrage and desperation of women came roaring through, targeting the dictatorial and patriarchal regime by demanding the liberation of female bodies.

History of resistance

On Oct. 16 an Iranian sport climber, Elnaz Rekabi, competed without a hijab at a competition in South Korea while representing Iran. Rekabi later said her hijab had “inadvertently” fallen off. However, many remained skeptical of her explanation, believing Iranian officials had pressured her to make the statement. Large crowds cheered Rekabi when she arrived back in Tehran days later.

While the current uprising may seem new, it follows decades of women’s resistance. Feminist activism in Iran goes back to women participating in the Constitutional Revolution in 1906. Women played a critical role and engaged in political actions by establishing women’s associations, joining protests and supporting strikes.

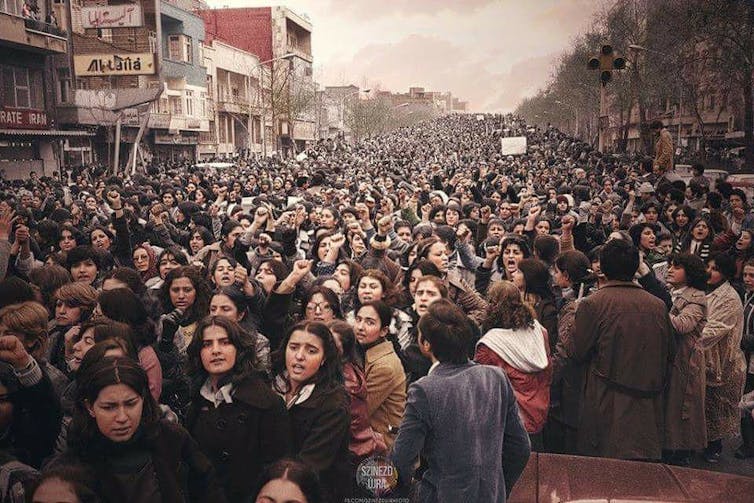

One month after the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iranian women launched massive demonstrations after hearing whispers about a hijab mandate. Although those protests were able to postpone the mandate, it was eventually instated in 1983.

Iranian women never stopped fighting. They turned their bodies into arenas of resistance against the ideology and intervention of the state. Acts of civil disobedience and campaigns like My Stealthy Freedom, White Wednesdays, The Girls of Revolution Street and the Iranian #MeToo movement were designed to sustain momentum in the fight against oppressive bodily regulation.

In Iran, women’s bodies have always been at the forefront of the political agenda. Mandatory dress codes are a central feature of the regime’s policy towards women. They function as a policing apparatus to control women’s sexuality and regulate their bodies.

While women face aggression on a daily basis for not following the state’s gender and sexual proscriptions, stubborn forms of female bodily presence on social media are an important part of the way women are able to fight the regime’s hegemonic narratives.

Under Iran’s authoritarian governments, collective action organized under strong leadership with effective networks of solidarity has been challenging, especially in the post-Islamic revolution era.

However, digital spaces and social media is providing more room for Iranian women and sexual minorities to keep up their resistance and pose critical challenges to the restrictive gender politics of the regime.

Alliance of marginalized groups

The long struggle for women’s rights has taken more radical forms since Amini’s death. The protests against the mandatory hijab law have expanded and targeted the very foundations of the regime and its ideological taboos. By linking the protests to broader discussions of gender, ethnic, social, economic and political protests, demonstrators have elevated it to a protest against the Islamic regime itself.

Amini’s identity as a Kurdish woman has made gender and ethnicity integral facets of the recent uprisings. It has created an inclusive alliance among religious, sexual and gender minorities, as well as suppressed ethnicities such as Kurds, Arabs, Turks, Balochs, Lors and others.

It is as if this intersection of oppressed identities has targeted the position of the Persian, Shia and heterosexual man as the hegemonic representative of the nation. Amini’s death has become the rallying cry for all the other subaltern counterpublics against the socio-political ideologies of the clerical regime.

Iranian women are de-ideologizing their bodies with anger (cutting off their hair and burning their hijabs) and joy (dancing). The female body, having been an object and symbol of a theocratic ideology, is now emerging as the most serious threat to the legitimacy of the regime. The ongoing uprising makes it clearer than ever that the liberated female body is the regime’s Achilles heel.![]()

Niloofar Hooman, PhD candidate, Communication Studies and Media Arts, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.