Mapping of carbon stores by McMaster researchers helping guide national restoration priorities

A study involving McMaster researchers highlights priority areas across Canada, that if converted back to their natural state, would help curb biodiversity loss and climate change.

BY Maureen Lawlor

April 17, 2023

Restoring up to 39,000 square kilometres of land in Canada (an area a little larger than Vancouver Island), would help curb biodiversity loss and climate change, according to a new study involving McMaster researchers.

The study, which was led by the World Wildlife Fund Canada (WWF-Canada), has identified the human-dominated areas, that, if converted back to their natural state, would yield the most benefit both in terms of carbon storage, and protection for species at risk.

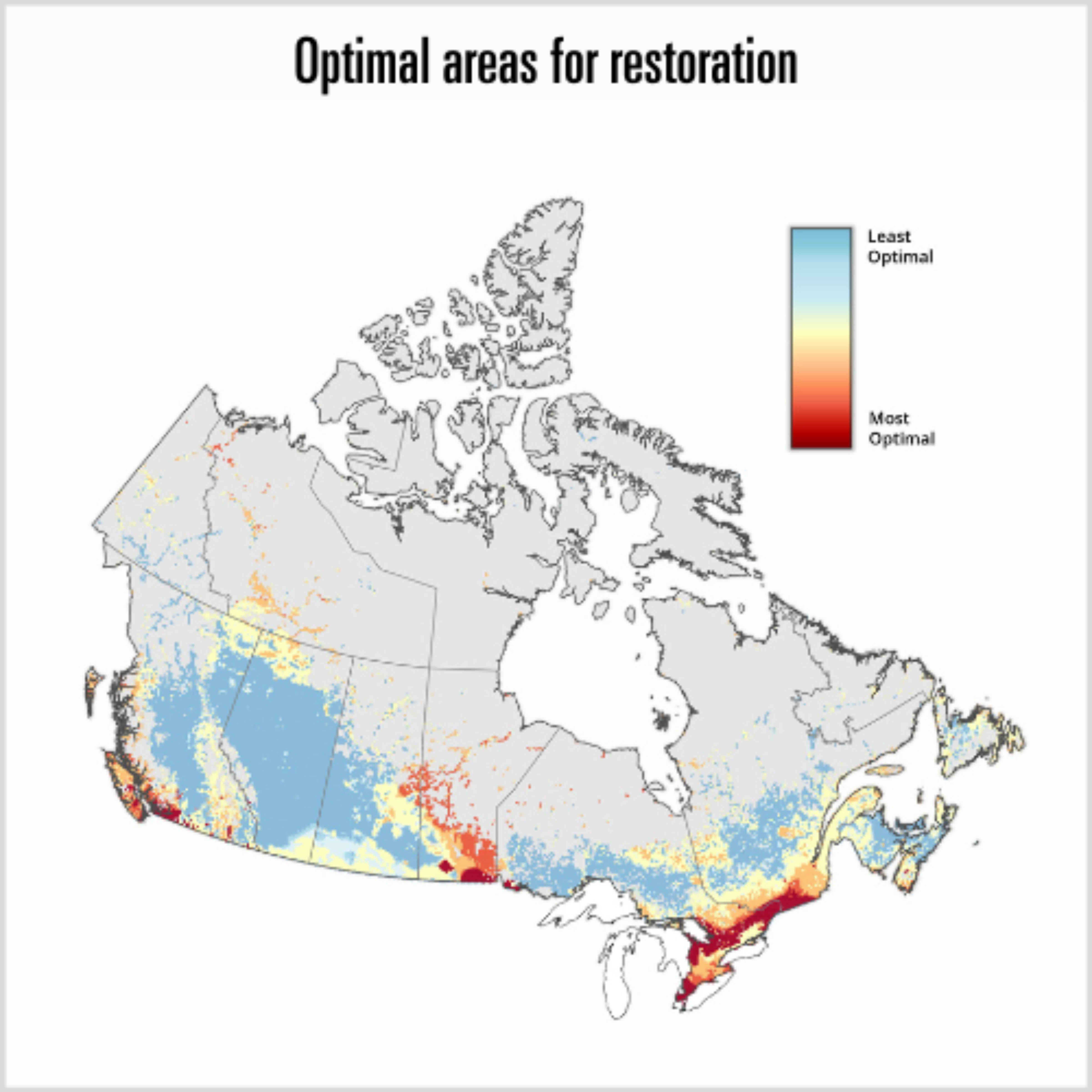

Areas for high-impact restoration were identified across the country, though priority areas were most commonly found in southern Ontario and Quebec, and southern Manitoba.

The study can serve as a guide to policymakers trying to help Canada meet its national and international goals around land protection and restoration, says Alemu Gonsamo, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Science and Canada Research Chair in Remote Sensing of Terrestrial Ecosystems.

The Canadian government has committed to 2030 restoration targets under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, and to restoring 19,000 square kilometres of degraded and deforested land by 2030 under the Bonn Challenge.

“This kind of scenario study — highlighting areas that are highly optimal, most optimal and optimal — is very useful for making decisions,” says Gonsamo. “So, this this is one of the tools that governments or policymakers at the national, local or municipal scale can consider.”

The study used and built upon the mapping of Canada’s carbon stores previously developed by Gonsamo and former McMaster postdoctoral researcher Camile Söthe at McMaster’s Remote Sensing Laboratory.

Those findings, which Gonsamo presented at COP26 in 2021, showed there is 327 billion tonnes of carbon stored in land ecosystems across Canada, including in soils up to one metre deep. If disturbed, it could have a massive global impact and would accelerate climate change.

In the News

Read more about McMaster’s Remote Sensing Laboratory and the mapping of Canada’s carbon reservoirs in The Globe and Mail, the CBC and Global News.

“Dr. Söthe and Gonsamo’s national carbon map served as a building block for the carbon component of our analysis,” says Jessica Currie, a senior specialist at WWF-Canada and lead author of the study. “We used their assessment of current carbon stocks to estimate the potential carbon benefits of restoring converted lands in Canada.”

The restoration of the land identified in this latest study would sequester up to 836 million tonnes of carbon — the equivalent of nearly five years of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Söthe says she is glad to see protection of high carbon storage areas and other nature-based climate solutions feature more prominently in discussions around the fight against climate change.

“Reducing carbon emissions and also protecting the current carbon stock is something that can really help us to limit climate change and global temperature rise,” says Söthe. “I can only see this growing as a solution for the environment long term.”

Gonsamo and his research team continue to build upon and refine their carbon mapping data, including spending last summer doing fieldwork and exploring the vast carbon-rich peatlands in the Hudson Bay Lowlands. The work, done in collaboration with WWF-Canada, includes working in partnership with Indigenous communities and training community members to gather more data from the region.

Gearing up for fieldwork season in Hudson Bay lowlands to map peat depth and carbon content at high spatial resolution and in southern Ontario to study forest management options to increase carbon stocks in soils and live biomass with @NSERC_CRSNG @WWFCanada @Mushkegowuk pic.twitter.com/VuDRMJDFtn

— Alemu Gonsamo (@AlemuGonsamo) June 14, 2022

Söthe says they are contacted regularly by other researchers and government officials looking to use their carbon mapping for other analyses.

“It’s a feeling of accomplishment because we always want our research to be useful,” says Söthe. “It’s amazing being a part of this and knowing it can help the environment and help in making decisions that direct conservation efforts.”