How a “radically practical” Greek and Latin course helps future health-care workers

Greek and Roman Studies professor Stephen Russell is demystifying the languages of medical science, and creating “the McMaster Translations” to help students understand anatomical terms.

BY Sara Laux, Faculty of Humanities

February 23, 2024

Quick – you’re working in health care, and you encounter a patient with brachiokinetalgia.

Do they need a ventilator? A tourniquet? A painkiller? Are they doomed?

Students in the two Ancient Roots of Medical Terminology classes, taught in the department of Greek and Roman Studies, will recognize the Greek building blocks of the word right away: “-algia” means pain, “kinet” means movement, and “brachio-” means arm.

So brachiokinetalgia means pain in the arm when it moves, right?

Not quite. The order of those building blocks actually describes pain when the arms move — which means the pain could be in the arms, but it could also be in the back or the neck or the little toe.

This kind of mix-up, says course instructor Stephen Russell, is why it’s so important for his students — who come from programs like kinesiology, health sciences, nursing and rehab science — to learn a systematic way of translating the massive, specialized vocabularies they will encounter working in health care.

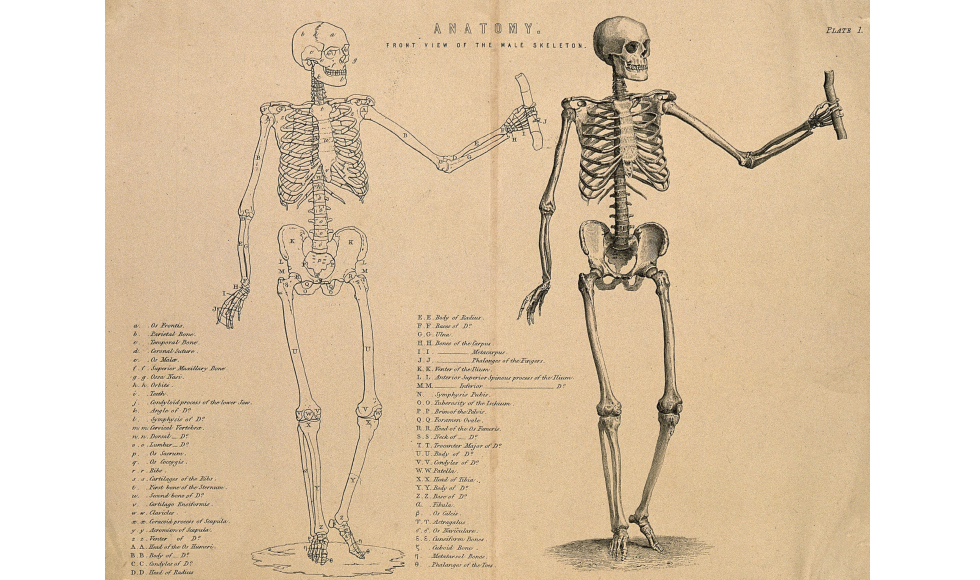

After all, most students don’t study Latin and Greek — but these are the languages of health care, especially when talking about anatomy (Latin) and describing clinical things like diseases, procedures, and symptoms (Greek, mostly).

Mandible, vertebrae and abdomen: Latin.

Hemorrhage, dermatitis and rhinoplasty: Greek.

“There are a lot of potential problems if people misunderstand anatomical language or medical language, and a lot of that may be because they don’t understand the terms they’re using,” Russell explains.

“We’re trying to help students learn the terminology without feeling like they have to memorize everything. There’s an inherent logic to the order that things come up.”

That means teaching students the common roots in the vocabulary of health care.

For example, the termination (or word ending) “-itis” comes up a lot, because it means inflammation. “-ectomy” is familiar to anyone who’s had their appendix or tonsils removed.

From there, students learn the predictable ways the roots combine. So even if they’re faced with an unfamiliar word, they can break the elements apart and figure out whether they’re dealing with someone with arm pain or someone who gets a pain in their neck when their arms move.

Anatomy for English speakers

“In this term alone, I used my knowledge from both medical terminology courses in three different classes,” says Sonia Chernov, a third-year kinesiology student.

“The emphasis on practicality was clear in the first course, where the focus was on the most important roots of medical vocabulary and foundational Latin grammar.”

The same strategy applies when learning the Latin that is used in anatomical terms — which includes the more than 7,100 Latin terms in the Terminologia Anatomica (TA2), the worldwide standard nomenclature for anatomy, most recently updated in 2019.

But the TA2 itself is hampered by many practitioners’ unfamiliarity with Latin. Available as a website and a searchable PDF, it provides the Latin names for anatomical structures in the human body, and also provides an English vernacular equivalent: Mandible = jaw.

Pretty straightforward, right?

Surprisingly not, says Russell. The problem lies in the English terms, which don’t always reflect a precise translation of the Latin. That leads to confusion and potential misuse, especially when colleagues of different nationalities need to interact.

Take the Latin term vena anterior, for instance.

While the vernacular equivalent is anterior vein, trouble arises when someone isn’t entirely sure what “anterior” actually means. That’s why a literal translation — substituting the word “front” for anterior — is so necessary.

The McMaster Translations

Russell and his colleagues are now working on a set of translations for the TA2 — literal renderings of the Latin terms in English that bridge the gap between the formal Latin and the commonly used English equivalents.

“The people who use the TA2 don’t know what these names in Latin mean, and how they connect to the vernacular versions that are used on a daily basis — they see these Latin names almost as bar codes, and they memorize them without understanding,” says Russell.

“Having this new column fitting into the Terminologia Anatomica will help people understand by showing the relationships between words.”

Related to those translations — which are known, for now, as the McMaster Translations — is the desire to work with those who make decisions about the nomenclature in the TA2 to come up with a consistent system for naming new anatomic structures, or what are known as “variant parts.”

“There are about 7,500 names for things in Latin that everyone uses throughout the world, but there are thousands and thousands of possible things coming up in variant anatomy that people don’t have a system to name,” Russell says.

“The naming system is in Latin and they don’t know how to use it.”

Radically practical

Although Russell’s own academic background is in Latin poetry — Ovid especially — he finds the work in medical terminology as exciting because it has so many practical applications.

“Teaching medical terminology is very different from anything else we do in Greek and Roman studies — I call it radically practical,” he says.

“It’s a service, and we do this service better than anyone else can, because we understand the theory behind the words, and can also place them in the context of the real world.”

Along with Ancient Roots of Medical Terminology (GKROMST 2MT3) and Advanced Ancient Roots of Medical Terminology (GKROMST 3MT3), the department of Greek and Roman Studies also offers a concurrent certificate in the Language of Medicine and Health. Find out more on the Greek and Roman Studies webpage.