Exploring and understanding queer Caribbean worlds

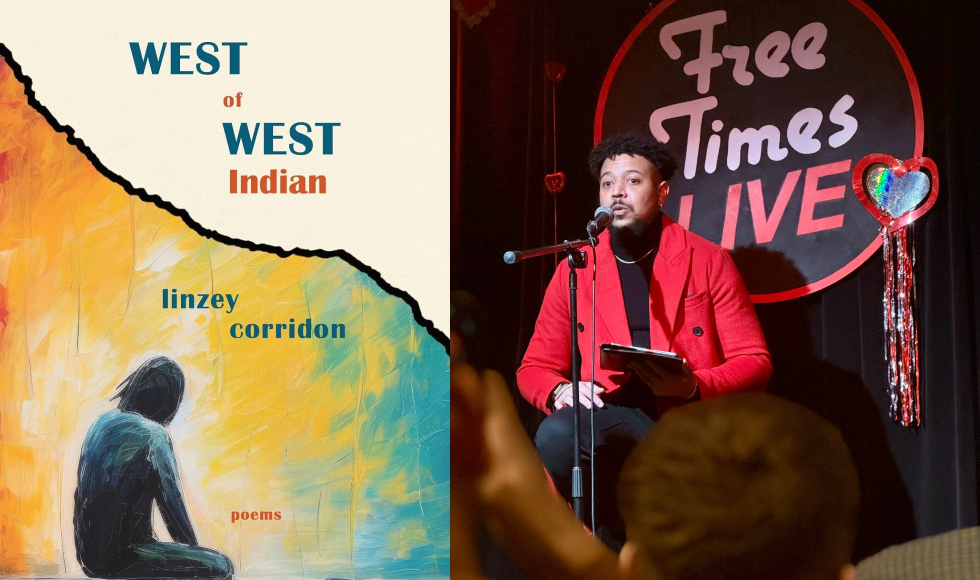

Graduate student Linzey Corridon’s recent poetry project, West of West Indian, and his PhD dissertation have a symbiotic relationship.

July 3, 2024

As he was working on his master’s degree, Linzey Corridon found himself drawn to works by queer Caribbean (Queeribbean) writers whose work reflected experiences that, for him, felt strangely familiar. And while he continued his academic work, eventually starting a PhD in McMaster’s Department of English & Cultural Studies, he found himself wanting to contribute his own creative work to the growing body of Queeribbean literature.

Now, the 2021 Vanier Scholar and PhD candidate, originally from St. Vincent and the Grenadines, has published his first book of poetry, West of West Indian, which was recently included on CBC’s list of poetry collections to watch for in Spring, as well as one of its 35 books for Pride month.

We spoke with Corridon about the inspiration for his book, and the relationship between his creative work and his PhD dissertation.

Can you talk a little about the genesis of the book?

When I was a master’s student in Montreal, I was completely enamored with Faizal Deen’s land without chocolate, a text charting some of the experiences shaping the sexually nonconforming Indo-Caribbean experience.

I remember coming across the poetry collection and thinking Why does this feel so familiar? Why am I haunted by the experiences of a figure who I knew nothing of prior to coming to the collection?

At the same time, I recognized that what felt familiar was the speaker’s attempts to chart their own wayward, often challenging, pathways to Caribbean desire and queer expression. The experience was familiar, but it was not my own.

I could identify with some of the psychic and material struggles, but I also recognized that our articulations of Caribbean desire and queer expression ultimately diverge away from those more common struggles towards the particularities that make the lives of Queeribbean people so diverse and meaningful beyond the more common narratives dictating public perceptions.

I knew two things were certain during the space of the MA. I wanted to keep tracing the maps I could see and feel that sustained the queer lifeworlds familiar to myself and others like me, but I also wanted to attempt a kind of mapping of my own beyond the space of the master’s and the major research project. I felt that this mapping work would best thrive in the space of my creative writing.

I felt a sense of urgency to add to the burgeoning body of Queeribbean literature sustaining lifeworlds beyond the more popular understandings of our experiences. I wanted to tease apart some of the complexities that tied my life to other lives around me, many of them queer and queered because of their Caribbean ontologies.

West of West Indian would then slowly come together as I attempted the work of mapping the ever-transforming space of living my iteration of a Queeribbean life. I take inspiration from the people who shaped my experiences of island and diaspora living — whether these individuals intended this is unclear to me — and I map one boy-turned-man’s coming to terms with muddied themes such as love, loss and longing.

What was it like to juggle the demands of a PhD program with a full-length book project?

I came into the PhD at McMaster not wanting to deliberately tie up my academic research with my creative writing praxis. I am not a trained creative writer like many of my colleagues, so there were several personal doubts as to whether I possessed the skills necessary to formally put this work together while sustaining the research practice necessary to succeed in the PhD.

Processes such as querying publishing houses, the politics of navigating the book contract, working with a seasoned editor to refine the manuscript, are all examples of skills I learned while doing my best to stick to the stipulated PhD timeline.

Now, in my fourth and final year of my PhD, I can say that my mindset has shifted drastically concerning the relationship between my creative practice and my academic pursuits. This realization is largely due to having an encouraging PhD committee who recognize and understand the symbiotic relationship between my creative and academic pursuits.

I realize now that much of the savvy and skills required for completing the PhD proved useful in securing the book contract. I can also say that my creative writing practice, particularly my preoccupation with the mundane, seemingly less spectacular aspects of Queeribbean life have further refined my thinking through of the dissertation project.

How do the two projects inform or influence each other?

I would say that the fundamentally shared quality between West of West Indian and my dissertation entitled Small-Island Intimacies: The Fluid Queeribbean Quotidian in Polymorphic Anglophone Caribbean Nation-States is the question of how we name and understand everyday queer Caribbean worlds.

They are both projects which attempt to transform conversations about how we create, deploy, and sustain identity categories. Both projects are interested in a theory of materialism and the quotidian which highlights how our simplest, often taken-at-face-value relationships to the material world inform micro and macro sociocultural and political structures governing queer life on a local, regional and global scale. Our understandings of a particular category like queer or Caribbean are usually tied to how we position ourselves within these political structures.

Both projects attempt to generate a space in which we might understand the usefulness of the language of categories and role that the individual continues to play in the (de)construction of frameworks governing Caribbean and diaspora living.

Who (or what) inspires or influences you?

There are many people, things, ideas that inspire me and my work. For the purposes of this interview, I will list a few of the inspirations that sustained the first book project. I harbour an unwavering love of poetry. I am indebted to the writings of poets including Dionne Brand, Kamau Brathwaite, Ishion Hutchinson, Richard Georges, Faizal Deen and more.

I am also indebted to the everyday sexually and gender nonconforming West Indians who, while I am defining my relationship to queerness and the Caribbean, continue to leave material and psychic traces of themselves for others to learn from and to live with.

I am here and this book is a reality because of the existence of one shopkeeper in Kingstown, because of an octogenarian whose home remains a safe space for younger generations, and because of a spiritual leader who decided that walking the unmapped path wouldn’t result in a life being squandered.

These humans are but a few examples of the traces vital to the continuation of Caribbean histories and Queeribbean literary genealogies. I suspect that the people will always show up in my work, be it creative or academic, because I am still mining the impacts of their traces to this day.