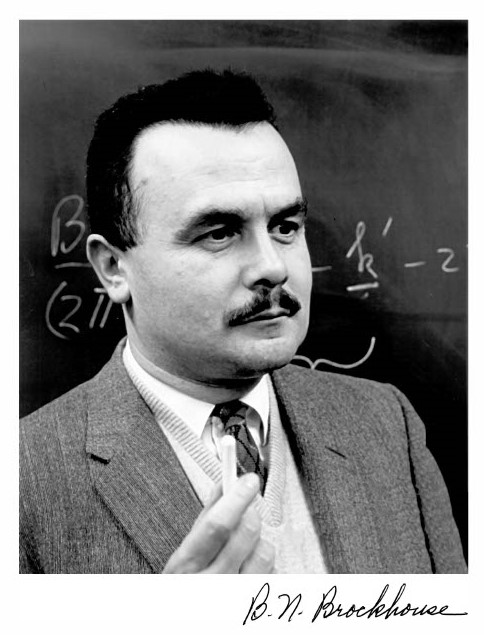

Remembering Bertram Brockhouse: McMaster professor emeritus and Nobel Prize laureate

Nobel Prize winner Bertram Brockhouse at Chalk River Laboratories with the first version of his triple-axis spectrometer in the late 1950s. The 1994 Nobel Prize in Physics awarded to Brockhouse and MIT professor Clifford Shull demonstrated the importance of neutron beams as scientific tools.

BY Jay Robb, Faculty of Science

September 10, 2025

Bertram Neville Brockhouse had big news to share with family and friends in his annual Christmas letter back in 1994.

“If anyone cares, we got a new car in the summer – a Chrysler Neon.”

Later that fall, Brockhouse got one half of the Nobel Prize in Physics. The McMaster professor emeritus was recognized for his development of neutron spectroscopy while the other half of the prize went to MIT professor Clifford G. Shull for his development of the neutron diffraction technique.

In a media release announcing the award, the Royal Swedish Academy of Science wrote, “ in simple terms, Clifford G. Shull has helped answer the question of where atoms ‘are’ and Bertram N. Brockhouse the question of what atoms ‘do’”.

Brockhouse’s path to the world’s most prestigious prize began when his parents quit farming in Southern Alberta to try their hand at running a rooming house and a grocery store in Vancouver. When he wasn’t in school or slinging newspapers to help his family make ends meet, Brockhouse hung out in radio repair shops and built his own sets.

It was clearly time well spent. Decades later, Brockhouse was asked to give one piece of career advice to aspiring scientists. “Learn to tune your mind like a radio, filtering out all the noise and other channels, focusing on one thing.”

In 1939, he put his aptitude for electronics to work in service of Canada’s war effort by enlisting as an electronics technician with the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve. “I was profoundly anti-totalitarian and hence anti-communist so that when World War II erupted, I was motivated from many sides to join the military.”

He spent six months at sea, and the next six years on shore, working on anti-submarine detection equipment. In the final year of the war, Brockhouse was a newly-minted electrical sub-lieutenant assigned to the National Research Council’s test facilities in Ottawa where he met Doris Miller, a film cutter with the National Film Board, and his future wife.

When the war ended in 1945, Brockhouse returned to Vancouver. The Department of Veterans Affairs gave more than a million ex-servicemen and women the opportunity to get a university education. Brockhouse opted for an bachelor’s degree in physics and mathematics at the University of British Columbia.

The next summer, Brockhouse drove his motorcycle back to Ottawa. “This was probably a decisive step in my life because I took up with Dorie again.”

He returned to Vancouver one last time, completed his bachelor’s degree with first class honours, then returned to Ottawa, where he landed a summer job with the National Research Council and proposed to Miller. They married in 1948.

After earning his PhD in physics at the University of Toronto, Brockhouse joined the National Research Council’s Atomic Energy Project. In 1950, Brockhouse joined the neutron physics group at Chalk River Laboratories as a research officer. The newlyweds and first-time parents bought a house in neighbouring Deep River and soon after had their second child.

“One wonders if the Brockhouses appreciated how cold Chalk River could be in the winter or how isolated it must have been in 1950,” wrote Roger Cowley for the Royal Society.

The plan was to stay at Chalk River for only few years and then join academia. “We stayed for 12 years and four more children,” said Brockhouse.

It was in a faded blue-shingled wartime hut at Chalk River that Brockhouse began mulling over and working through the equations that would drive his Nobel Prize-winning work on the inelastic scattering of neutrons. “Using beams of neutrons the same way as a microscope uses light, he was able to reveal the movement of atoms in condensed matter and thus probe into the mysteries of crystal structures and other solids such as metals, minerals, gems and rocks,” wrote the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada in announcing the Brockhouse Canada Prize for Interdisciplinary Research in Science and Engineering.

It was in a faded blue-shingled wartime hut at Chalk River that Brockhouse began mulling over and working through the equations that would drive his Nobel Prize-winning work on the inelastic scattering of neutrons. “Using beams of neutrons the same way as a microscope uses light, he was able to reveal the movement of atoms in condensed matter and thus probe into the mysteries of crystal structures and other solids such as metals, minerals, gems and rocks,” wrote the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada in announcing the Brockhouse Canada Prize for Interdisciplinary Research in Science and Engineering.

By 1958, Brockhouse had designed and built the first triple-axis neutron spectrometer to accurately measure inelastic neutron scattering. Scientists from around the world made pilgrimages to Chalk River to learn Brockhouse’s pioneering new methods for neutron spectrometry and his spectrometer was used as a training ground for more than 20 years at Chalk River.

“Today, triple-axis neutron spectrometers are used by physicists in laboratories worldwide to study the structure of condensed matter in areas ranging from chemistry and medicine to metallurgy and nuclear power,” wrote NSERC in their Brockhouse biography.

Brockhouse was appointed head of the newly formed Neutron Physics Branch at Chalk River in 1960.

Two years later, Brockhouse made his long-delayed moved to academia, joining McMaster as a physics professor. “I preferred not to join a mega-university or live in a mega-city, partly because I thought that it would be better for our family of six children.”

Awards and accolades soon followed. During his first decade at McMaster, Brockhouse was appointed a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the Royal Society of London and received the Oliver S. Buckley Prize of the American Physical Society, the Duddell Medal and Prize of the Institute of Physics, the Medal for Achievement in Physics from the Canadian Association of Physics, the Centennial Medal of Canada and the Royal Society of Canada’s Tory Medal.

While his research using neutron scattering techniques stopped in 1973, Brockhouse earned a reputation as a conscientious supervisor who was quick to share his four rules for becoming a successful research student:

- An experimentalist has to ensure that his data are correct.

- He should use his intuition, especially if it is good.

- Work takes precedence over coffee breaks and reading newspapers.

- A research student does not have a nine-to-five job.

In a biography published to commemorate Brockhouse’s retirement in 1984, scientist John Copley credited his former professor and McMaster colleague with demonstrating an honesty, thoroughness and scientific passion throughout his career. “The ‘absent-minded professor’ stories are plentiful, and amusing, but the stories of his insistence on good experimental technique, and of his concern that time and money be efficiently used, are perhaps more to the point. His intuition, his dedication to research, and his kindness and concern for his fellow workers, are frequently mentioned by those who have had the pleasure to work with him.”

Ten years after retiring – and nearly four decades after his pioneering work at Chalk River – Brockhouse was awarded one half of the 1994 Nobel Prize for Physics. He woke up on the morning of Oct. 12, at home in Ancaster, to find a message waiting on his answering machine.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences had called to say that “B. N. Brockhouse and C. G. Shull have been selected as recipients of the 1994 Nobel Prize for physics.” He replayed the message for his wife, who was the first to learn that her husband was now a Nobel Laureate. And then their phone started ringing and never stopped for the rest of the day.

“My greatest debt is to my wife of 46 years and my family, whose support and encouragement were indispensable and total,” Brockhouse wrote in his Nobel Prize biographical.

“Brockhouse was simply beamed out of quiet retirement,” wrote the American Crystallographic Association in their profile of the Nobel Laureate. “The next year was one of travel, awards, banquets and lectures.”

Brockhouse, who’d been made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1982, was promoted to Companion in 1995. McMaster’s Institute for Materials Research – the university’s oldest and largest research institute and one that Brockhouse had served on as a founding member – was renamed the Brockhouse Institute for Materials Research. Two streets – one at McMaster and another at Deep River – were renamed in his honour. The Canadian Association of Physicists and the Division of Condensed Matter and Materials Physics created the Brockhouse Medal to recognize outstanding experimental or theoretical contributions to condensed matter and materials physics. And NSERC’s first Brockhouse Canada Prize for Interdisciplinary Research in Science and Engineering was awarded in 2004.

Brockhouse, who’d been made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1982, was promoted to Companion in 1995. McMaster’s Institute for Materials Research – the university’s oldest and largest research institute and one that Brockhouse had served on as a founding member – was renamed the Brockhouse Institute for Materials Research. Two streets – one at McMaster and another at Deep River – were renamed in his honour. The Canadian Association of Physicists and the Division of Condensed Matter and Materials Physics created the Brockhouse Medal to recognize outstanding experimental or theoretical contributions to condensed matter and materials physics. And NSERC’s first Brockhouse Canada Prize for Interdisciplinary Research in Science and Engineering was awarded in 2004.

Brockhouse passed away on Oct. 13, 2003.