A Peruvian Andean adventure

July 14, 2017

From May 25 to June 11, the Glacial Sedimentology Lab, led by Dr. Carolyn Eyles, worked with Peruvian scientists from the National Institute for Research in Glaciers and Mountain Ecosystems (INAIGEM) to understand the glacial systems and water issues in the region of the Santa River Basin, Perú. Eyles is the Director of the Integrated Sciences program and a professor in the School of Geography and Earth Sciences.

The trip to Peru, part of a 2016 Memorandum of Understanding between McMaster and INAIGEM to foster research, education and community service in areas of glacial and ecosystem change and development, was partially funded through a grant from the Office of International Affairs’ International Initiatives Micro Fund.

During the three months they spent in Peru, the McMaster team journeyed into the Andean glacial mountains to collect field data, delivered a two-day courseto INAIGEM staff and local university students, and visited the Embassy of Canada to Perú to discuss McMaster’s initiatives in Peru and how to explore potential educational exchanges between McMaster and Peruvian universities. The following chronicles the team’s experiences and the insights they gained on this unique trip:

Hello! We are the Glacial Sedimentology Lab: Chimira Andres, David Bowman, and Rodrigo Narro Perez. We are supervised by Dr. Eyles. This summer we travelled to Huaraz, Perú to conduct research, tackle some field work, and collaborate with other Peruvian field teams in order to study a natural disaster called Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOF) in the Cordillera Blanca, Andes.

From left to right: Oscar Vilca (INAIGEM), Chimira Andres (McMaster), David Bowman (McMaster), Marco Zapata (INAIGEM), Dr. Carolyn Eyles (McMaster), Rodrigo Narro Perez (McMaster), Harrison Jara (INAIGEM).

From left to right: Oscar Vilca (INAIGEM), Chimira Andres (McMaster), David Bowman (McMaster), Marco Zapata (INAIGEM), Dr. Carolyn Eyles (McMaster), Rodrigo Narro Perez (McMaster), Harrison Jara (INAIGEM).

WHAT DO WE DO IN THE GLACIAL SEDIMENTOLOGY LAB?

The Glacial Sedimentology Lab is interested in the study of sediments – bits of rock and debris – that are deposited by glacial processes. The size, location, and the structures of these sediment can give unique insight into what processes deposited them, and when it occurred. We use this information to help understand past environments, how a glacier has advanced and retreated over time and to help predict what may occur in the future.

The study of sediments is also important for water issues, as the manner in which water flows on the surface and through the ground is dependent on the nature of these sediments.

Chimira is standing at the bottom of one of the sediment profiles that we measured in the Cojup Valley. By analyzing these sediments we can understand the past environmental processes of this valley, especially after the 1941 Lake Palcacocha GLOF.

Chimira is standing at the bottom of one of the sediment profiles that we measured in the Cojup Valley. By analyzing these sediments we can understand the past environmental processes of this valley, especially after the 1941 Lake Palcacocha GLOF.  Lake Paron is one of the many glacial lakes found throughout the Cordillera Blanca. Field work in this site involved looking at outcrops and sediments to understand the evolution of the lake.

Lake Paron is one of the many glacial lakes found throughout the Cordillera Blanca. Field work in this site involved looking at outcrops and sediments to understand the evolution of the lake.  McMaster at INAIGEM as part of the 4-part Glacial Sedimentology Workshop Series taught by Dr. Eyles

McMaster at INAIGEM as part of the 4-part Glacial Sedimentology Workshop Series taught by Dr. Eyles

FAVOURITE PART:

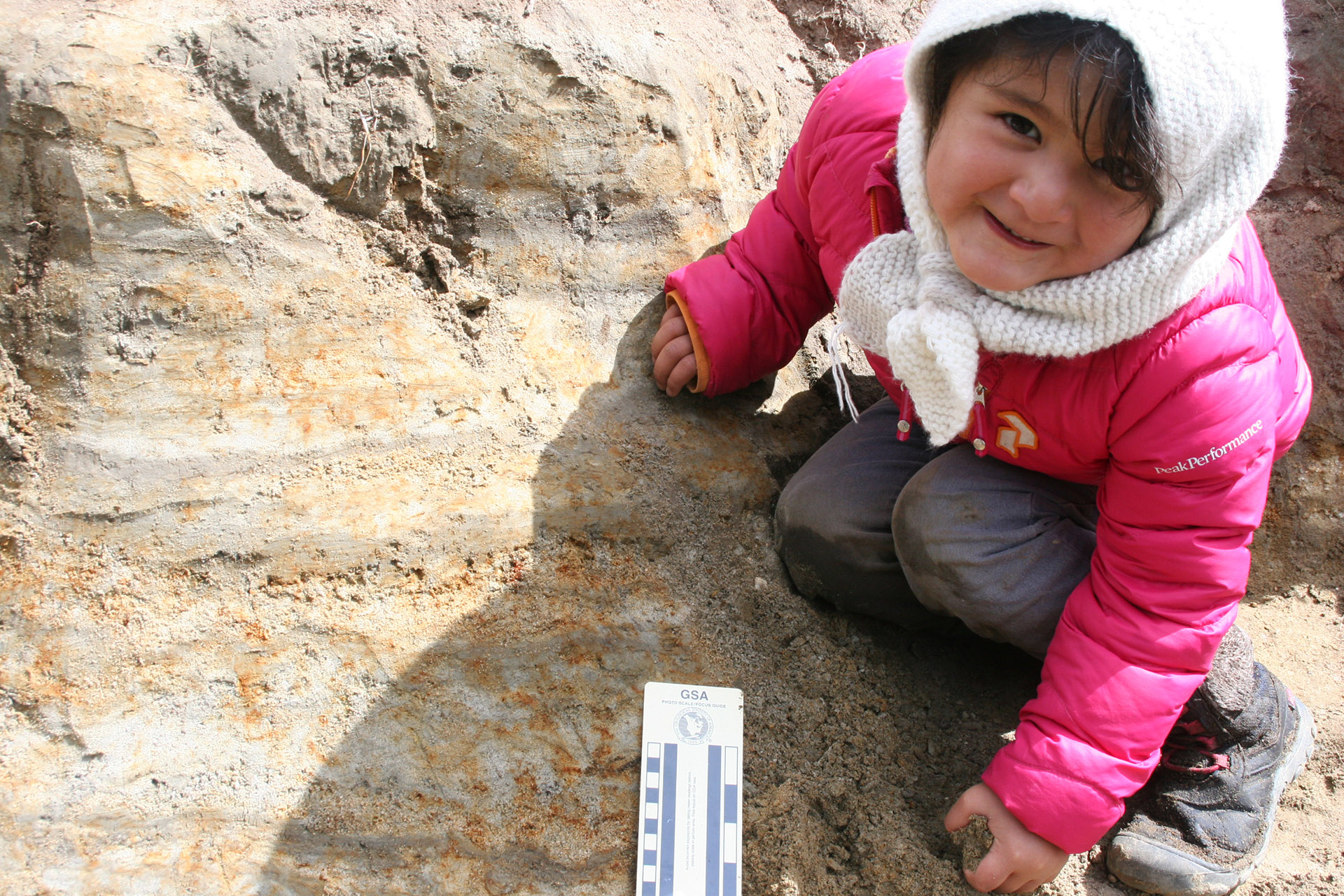

Chimira: One of my favourite parts of the trip was not only seeing the Andean landscapes but meeting different people and making friends. There were a few language barriers, Spanish to English, to be more specific, but that did not stop us from communicating to one another. Using Google Translate and hand gestures, we realized that there is always a way. One of our new friends was a three-year old girl named Mikaela and it is safe to say that she was the “crowd-favourite”. Mikaela is the daughter of one of the Environmental Geologists at INAIGEM, Luzmila Davila, who accompanied and guided us during our field work days. When we were struggling to hike through valley after valley, Mikaela would always have the brightest face on with an undying sense of positivity and energy. She would run up and down the river banks, uplifted geologic landscapes, and help out with the field work! She would gladly offer to do a sediment texture test, dig a sediment pit, and even take pictures with the landforms for scale. Her energy was contagious and the Spanish-English language barrier was suddenly non-existent! It was a joy having her there during some of our field days as she truly boosted the morale of the McMaster-INAIGEM team with her spirit. She was given the title, ‘Future Geologist/Glacial Sedimentologist’ for her sheer enthusiasm of the mountains and what they had to offer. By the end of the trip, you could tell everyone was sad to leave because we would miss our little geologist.

Mikaela alongside Chimira and INAIGEM scientists are measuring a river bank outcrop in the Rajaculta valley, one of the many sites we visited in our trip.

Mikaela alongside Chimira and INAIGEM scientists are measuring a river bank outcrop in the Rajaculta valley, one of the many sites we visited in our trip.

David: If I have to pick one thing in particular, my favourite part would be our first visit to the Palcaraju glacier, the glacier that occupies the slopes surrounding Lake Palcacocha. Our journey up to the lake through the Cojup Valley involved many stops to investigate key geologic or glacial features leading up to the valley’s terminus, and at each stop I paused to take in my surroundings. The skyward-stretching peaks were of a scale I had never seen before, and took my breath away as our two-truck convoy made its way to Lake Palcacocha. However, the view once we reached the lake was a totally different level. It was around this time that my camera died. Once I picked my jaw up off the ground, I took in the enormous lake with the glistening Palcaraju glacier hanging ominously above it. Not unlike the mountain peaks we had seen on our way up, the scale was like something out of this world. I had previously visited glacial lakes in Alberta, BC, and Iceland, but Palcacocha was unlike anything I had ever seen before. Shortly after asking, “Is an icefall or rockfall into the water a concern at this lake?”, a great rumbling echoed across the water as a small avalanche detached from the icy rock face, sending debris into the distal end of the lake. We witnessed another two of these occurrences within the next hour, underscoring just how dynamic the seemingly stable, unmoving glacier body could be. We made our way down-valley with a firm plan for observations during our return the following day; I couldn’t wait to make our way back.

Lake Palcacocha created an outburst flood in 1941 that hit the city of Huaraz and killed over 5,000 people. Since then, this lake has been monitored consistently and many remediation tactics have been put in place – the tubing at the bottom of the picture is actively pumping water out of the lake to try and stabilize lake levels.

Lake Palcacocha created an outburst flood in 1941 that hit the city of Huaraz and killed over 5,000 people. Since then, this lake has been monitored consistently and many remediation tactics have been put in place – the tubing at the bottom of the picture is actively pumping water out of the lake to try and stabilize lake levels.

Rodrigo: This trip was incredibly meaningful to me. I was born in Lima, Peru and my family immigrated to Canada back in 2002 when I was 10. I would have never imagined that 15 years later, I would have played a big part in bringing a Canadian scientific team down to Peru to do collaborative research on glaciers and climate change. This research trip started as a small vision and hope that I had when I started my PhD with Dr. Eyles and without really noticing it, it spiralled into something bigger and more importantly, something more impactful. My favourite part of this trip was being witness to the countries that I hold so dear to my heart come together in this research trip. Whether it was simple conversations between the INAIGEM scientists and the rest of the Mac team or us doing field measurements together, I was able to see two groups of people working towards one common goal – how to better understand the environment, the glacial processes at play and the impact that these changes will have.

BIGGEST LESSONS LEARNED:

Rodrigo: One of the biggest lessons I learned was how important it is to engage the local communities and scientists whenever doing any type of international research. I had spent many months preparing for this trip by reading all the journal articles that I could find. But once I started talking to the INAIGEM staff (the local experts), I noticed that they had ample knowledge on the history and environment of the area that wasn’t present in my readings. Unfortunately, expert knowledge is not always present in our typical academic publications (even Spanish publications contained knowledge gaps). Too often, North American and European researchers will go to a place, do their research, leave and publish their findings in journals. This doesn’t really build partnerships with the local scientists of the area who would not only provide expert knowledge on the area but would also benefit from this partnership. The Cordillera Blanca is experiencing rapid glacier retreat, something that all of the people in the region are witnessing first hand. Unfortunately, as is the case with most communities where research occurs, the people of the Callejon de Huaylas (the name of the region where we did our research) are not always communicated the results of this research and how it impacts their daily life. One of the things that we are working with INAIGEM with is ensuring that all our research is communicated to the local people (in one form or another) and I’m extremely happy and honoured to be part of that.

Chimira: From my personal perspective, this field trip introduced me to a variety of surreal experiences that an undergrad researcher could only hope for. From the Pacific coast, to the Lima desert, to the Andean glacial mountains, and finally to to the Amazon, Perú really does have a lot of diversity to offer. It is the perfect place for an enthusiastic biophile, like me! But the part that I was most excited about was immersing myself in field work, research, and communicating this to other fellow scientists from across the globe. And speaking of communication, one of the biggest lessons that I learned is that even though language barriers do exist, nothing will come in between hard and fast science. I learned that although science can indefinitely be interpreted in many ways, in different parts of the world, and in various languages, at the end of the day, we all still work towards the same goal to accomplish the same tasks; Science comes in simply to back everything up.

David: For me, one of the most eye-opening parts of our journey to Perú was seeing the types of environmental issues that the country faces. We often read about projections of climate change and the adverse effects it will have on our planet in the near future, but for the communities of the Andean highlands, these consequences are happening now. Accelerated glacier retreat in the past several decades has given rise to a host of natural hazards – flooding and ice avalanches among them – but also to issues related to water policy and supply that affect the entire country, from the mountains to the coastal capital city of Lima. To hear the scientists at INAIGEM talk about these issues through a lens of practical resolution, rather than one of despair, was very inspiring. As we begin our work here at McMaster, I am personally tremendously excited to continue collaborating with INAIGEM and contributing to a solution for these efforts.

OUTCOMES:

The trip was filled with full days (and evenings!) as we tried to achieve all of our objectives. Here are some of the outcomes that we were able to achieved throughout our three weeks in Perú.

- Successfully delivered a 2-day short-course called “Introduction to Glacial Sedimentology” to 20 INAIGEM staff and local university students.

- Collected field data for four projects. Each project is composed of a team with McMaster staff and INAIGEM staff – we are ensuring that all projects are truly collaborative. Rodrigo is leading two of these projects and David and Chimira are leading one each.

- Visited the Embassy of Canada to Perú to discuss McMaster’s initiatives in Peru and how to explore potential educational exchanges between McMaster and Peruvian universities.

In terms of what comes next, we have lots to currently do (especially analyzing our data and publishing our results!) but we know that this is the start of a very fruitful and exciting partnership!

McMaster and INAIGEM teams looking at a geological map of the area. On the left of the image you can see the city of Huaraz which acted as our base of operations for the trip. On the top right of the picture, in the distance, you can see Mount Huascarán, the highest mountain in Peru with an elevation of 6768 masl.

McMaster and INAIGEM teams looking at a geological map of the area. On the left of the image you can see the city of Huaraz which acted as our base of operations for the trip. On the top right of the picture, in the distance, you can see Mount Huascarán, the highest mountain in Peru with an elevation of 6768 masl.