Analysis: Bones and teeth help reveal whether teenagers have always been a source of worry for their parents

Today, teens are often seen as troublesome and difficult. Ancient Roman writers also described adolescence as a period of “hooliganism and debauchery.” (Shutterstock)

BY Creighton Avery, PhD Candidate, Department of Anthropology

January 11, 2022

They were promiscuous, rarely home and thought they knew everything. They were teenagers from centuries ago, and by studying their bones and teeth, bioarcheologists can confirm that teens have always been a source of worry for their parents.

Today, adolescence is a tumultuous period of change and distress, with clinical research suggesting it is a key phase of development, responsible for long-term mental and physical well-being.

Yet even as we worry about teenagers’ well-being, the question remains: What does “normal” adolescence look like? Or what makes a “good” adolescence?

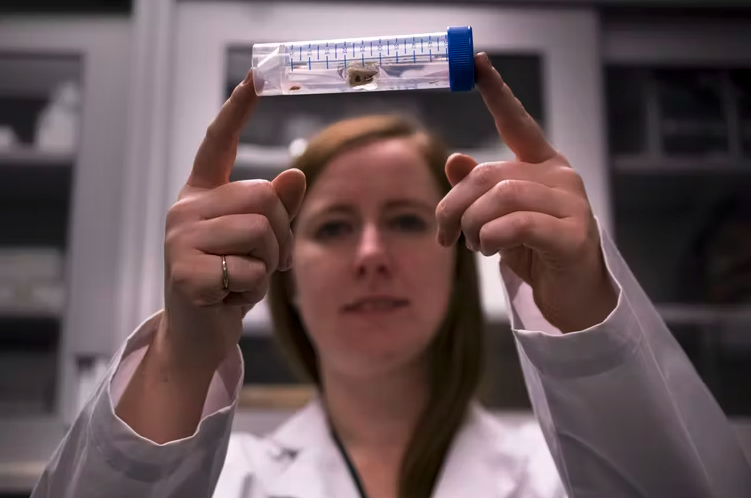

Bioarcheologists — people who study human remains from archeological sites — are trying to answer those questions. As a bioarcheologist, I examine bones and teeth to better understand when kids started to look like and act like adults in the Roman Empire (first to fifth centuries CE).

By examining bones and teeth, and incorporating archeological data, burial patterns, written sources and other lines of evidence, bioarcheologists are finding that teens today have a lot in common with teens of the past, but there’s one key difference.

(Creighton Avery), Author provided

Teenagers were innovative

In the Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 12,000 years ago) and Neolithic (around 12,000 to 6,500 years ago), teenagers were innovative and played an important role in the origin and spread of new ideas. They were highly mobile, creative and felt driven to meet and interact with new groups.

Similarly, teens today are creating more words, TikTok dances and social trends than any other age group. They’re also developing new ways to detect cancers and assess wounds, demonstrating that age is not a requirement for innovation.

Being “wired for innovation” may be due to the unique plasticity of the adolescent brain, which makes teens more open to learning new skills and taking on new opportunities.

So, rather than belittling adolescents for moving too fast or talking differently, we may need to put their innovative thinking to good use. That, and continue to have comedian Seth Meyers explain teen slang.

Teenagers tried on adult roles

For teens today, having a part-time job has short- and long-term benefits, including higher incomes and better networking skills later in life. However, there are some risks, particularly for those who work too much. Studying teens of the past shows us that this is not new.

Thousands of years ago, in the Neolithic, teens were practising to be adults, learning how to throw spears and hunt big game, joining adults in providing for their communities.

Similarly, in the Roman Empire 2,000 years ago, bioarcheological and ancient literary sources indicate young men began apprenticeships or joined the military under semi-protected status as teens, although this didn’t happen overnight and was a gradual process.

When these changes happened quickly, like in 18th-century Canada, teens faced poor health and well-being, mirroring patterns we see today. Those who take on full adult roles too quickly can face consequences, but a gradual transition has benefits.

Teenagers didn’t have an identity crisis

Today, teens are often seen as troublesome and difficult. Ancient Roman writers, too, described adolescence as a period of “hooliganism and debauchery,” when young men were encouraged to drink heavily and visit brothels (although recent bioarcheological research may suggest this is only true of wealthy families).

In the Upper Paleolithic, there was no “teenage rebellion,” likely because Paleolithic teens had a strong sense of self and belonging, as well as a sense of individual autonomy.

When moving from small, open-air communities to large, fortified communities in 13th-century Arizona, older children and teens found many of the activities that had helped create a sense of autonomy were gone. They no longer fetched water or worked with clay, making them less capable as farmers, hunters and foragers as they became adults.

And we may be seeing similar patterns today — teens are losing their autonomy by not having the opportunity to participate in adult roles. However, not all changes in 13th-century Arizona were negative. The move to larger communities also meant that these teens had greater opportunities to meet people, leading to new social skills and opportunities.

So because teens today aren’t given the same opportunities to participate in adult roles, they may be rebelling in an attempt to exert some form of autonomy and control over their lives.

Evolutionary basis for behaviour?

As bioarcheologists continue to explore adolescence, and what it was like to be a teen in the past, studies are showing that many of the behaviours we see today are not new.

Teens across millennia have yearned to explore, try new things and participate in risky behaviours. The key difference, however, seems to be the experience of a rebellion or restlessness, which does not appear to be a part of adolescence in the past: teens weren’t always wild.

Which raises the question — does a rebellious phase have to be part of adolescence today?![]()

Creighton Avery, PhD Candidate, Department of Anthropology, McMaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.