Analysis: Canada could use thermal infrastructure to turn wasted heat emissions into energy

Buildings are the third-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. (Yianni Mathioudakis/Unsplash)

BY James Cotton and Caleb Duffield

July 31, 2025

![]() James (Jim) S. Cotton, McMaster University and Caleb Duffield, McMaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

James (Jim) S. Cotton, McMaster University and Caleb Duffield, McMaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

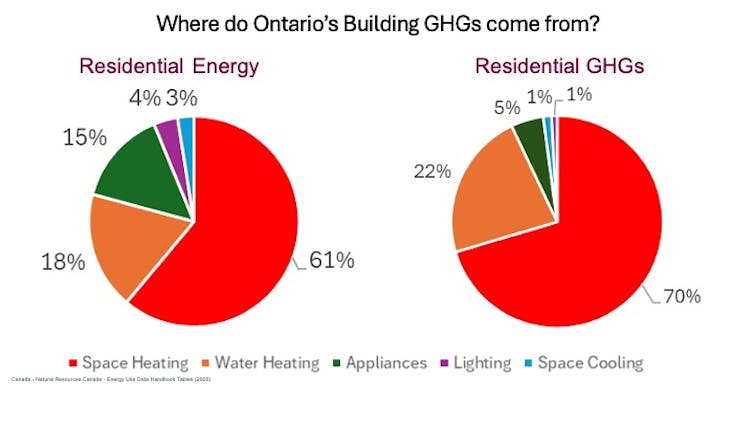

Buildings are the third-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. In many cities, including Vancouver, Toronto and Calgary, buildings are the single highest source of emissions.

The recently launched Infrastructure for Good barometer, released by consulting firm Deloitte, suggests that Canada’s infrastructure investments already top the global list in terms of positive societal, economic and environmental benefits.

In fact, over the past 150 years, Canada has built railways, roads, clean water systems, electrical grids, pipelines and communication networks to connect and serve people across the country.

Now, there’s an opportunity to build on Canada’s impressive tradition by creating a new form of infrastructure: capturing, storing and sharing the massive amounts of heat lost from industry, electricity generation and communities, even in summer.

Natural gas precedent

Indoor heating often comes from burning fossil fuels — three-quarters of Ontario homes, for example, are heated by natural gas. Until about 1966, homes across Canada were primarily heated by wood stoves, coal boilers, oil furnaces or heaters using electricity from coal-fired power plants.

After the oil crisis of the 1970s, many of those fuels were replaced by natural gas, delivered directly to individual homes. The cost of the natural gas infrastructure, including a national network of pipelines, was amortized over more than 50 years to make the cost more practical.

Now, as the need to decarbonize becomes more pressing, recent studies not only emphasize the often-overstated emissions reductions benefits from using natural gas; they also indicate that burning this fuel source is still far from net-zero.

However, there’s no reason why Canadian governments can’t invest in new infrastructure-based alternative heating solutions. This time, they could replace natural gas with an alternative, net-zero source: the wasted heat already emitted by other energy uses.

Heat capture and storage

Depending on the source temperature, technology used and system design, heat can be captured throughout the year, stored and distributed as needed. A type of infrastructure called thermal networks could capture leftover heat from factories and nuclear and gas-fired power plants.

In essence, thermal networks take excess thermal energy from industrial processes (though thermal energy can theoretically be captured from a variety of different sources), and use it as a centralized heating source for a series of insulated underground pipelines connected to multiple other buildings. These pipelines, in turn, are used to heat or cool these connected buildings.

A substantial potential to capture heat similarly exists in every neighbourhood. Heat is produced by data centres, grocery stores, laundromats, restaurants, sewage systems and even hockey arenas.

In Ontario, the amount of energy we dump in the form of heat is greater than all the natural gas we use to heat our homes.

A restaurant, for example, can produce enough heat for seven family homes. To take advantage of the wasted heat, Canada needs to build thermal networks, corridors and storage to capture and distribute heat directly to consumers.

The effort demands substantial leadership from all levels of government. Creating these systems would be expensive, but the technology does exist, and the one-time cost would pay for itself many times over.

Such systems are already working in other cold countries. Thermal networks heat half the homes in Sweden and two-thirds of homes in Denmark.

These were offered to utility companies looking to expand district energy operations, and to consumers by incentivizing connections to such systems. Additionally, in Denmark, controlled consumer prices served a similar function.

At least seven American states have established thermal energy networks, with New York being the first. The state’s Utility Thermal Energy Network and Jobs Act allows public utilities to own, operate and manage thermal networks.

They can supply thermal energy, but so can private producers such as data centres, all with public oversight. Such a strategy avoids monopolies and allows gas and electric utilities to deliver services through central networks.

An opportunity for Canada

Canada has a real opportunity to learn from the experiences of Sweden, Denmark and New York. In doing so, Canada can create a beneficial and truly national heating system in the process. Beginning with federal government leadership, thermal networks could be built across Canada, tailored to the unique and individual needs, strengths and opportunities of municipalities and provinces.

Such a shift would reduce emissions and generate greater energy sovereignty for Canada. It could drive a just energy strategy that could provide employment opportunities for those displaced by the transition away from fossil fuels, while simultaneously increasing Canada’s economic independence in the process.

Thermal networks could be built using pipelines made from Canadian steel. Oil-well drillers from Alberta could dig borehole heat-storage systems. A new market for heat-recovery pumps would create good advanced-manufacturing jobs in Canada.

Funding for the infrastructure could come through public-private partnerships, with major investments from public banks and pension funds, earning a solid and secure rate of return. A regulated approach and process could permit this infrastructure cost to be amortized over decades, similar to the way past governments have financed gas, electrical and water networks.

As researchers studying the engineering and policy potential of such an opportunity, we view such actions as essential if net-zero is to be achieved in the Canadian building sector. They are also a win-win solution for incumbent industry, various levels of government and citizens across Canada alike.

Yet efforts to install robust thermal networks remain stalled by institutional inertia, the strong influence of the oil industry, limited citizen awareness of the technology’s potential and a tendency for government to view the electrification of heating as the primary solution to building decarbonization.

In this time of environmental crisis and international uncertainty, pushing past these barriers, drawing on Canada’s lengthy history of constructing infrastructure and creating this new form thermal energy infrastructure would be a safe, beneficial and conscientious way to move Canada into a more climate-friendly future.![]()

James (Jim) S. Cotton, Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, McMaster University and Caleb Duffield, PhD Candidate in Political Science, McMaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.