Analysis: Educated voters in Canada tend to vote for left-leaning parties while richer voters go right

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau shakes hands with New Democratic Party leader Jagmeet Singh as Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre looks on at a Tamil heritage month reception in January 2023. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

BY Simon Kiss, Matt Polacko and Peter Graefe

October 25, 2023

It is hard to miss the increasing attention dedicated to transgender rights in contemporary politics.

In 2015, Justin Trudeau made a quick reference to including discrimination on the grounds of gender identity in the Canadian Human Rights Act, implementing the change after the 2015 election.

There wasn’t a significant political reaction to the trend, however, until this summer when three Conservative provincial governments — in New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and Ontario — moved to adopt policies that restricted the independence of schools to recognize or affirm students’ gender identities and ensuring parental participation.

Clearly, an electoral divide is emerging on the issue.

Left vs. right voters

We argue this conflict results from a “diploma divide” in the Canadian electorate similar to what has been seen in other countries. Since the 1990s, parties of the left have increasingly been supported by educated voters, while parties of the right have increasingly been supported by richer voters and the less educated.

While political scientists initially noted this trend, it has been popularized more recently by noted French economist Thomas Piketty and his colleagues.

So why would educated voters turn to parties that traditionally support more working-class voters?

One answer is that higher education tends to push people to become both more socially liberal and more economically right wing.

Piketty and his colleagues argue that as parties of the left become dominated by educated voters, they adopt socially liberal positions that alienate their traditional working-class base. These less educated voters long supported leftist parties and their promises to redistribute income and wealth, but those promises have faded as leftist parties court the well-educated.

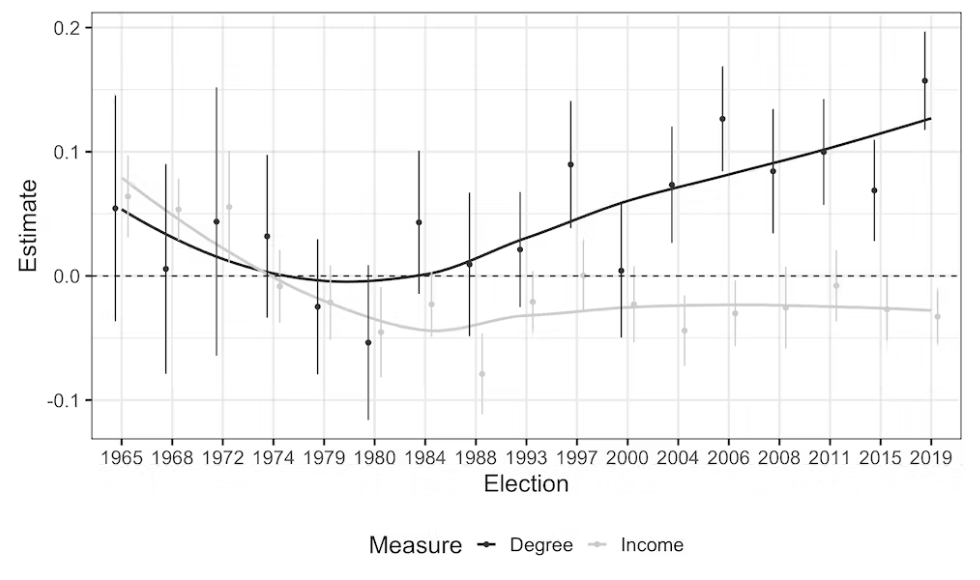

We extended Piketty’s research into the Canadian context in a recent article in Electoral Studies, using Canadian Election Study data from 1965 to 2019. The graph below compares the probability that voters with university degrees voted for the “left” — the NDP or Liberals — versus the “right,” including candidates running for the Conservatives, Progressive Conservatives, the Reform Party or the Canadian Alliance.

This is exactly the pattern Piketty and his colleagues identified. Educated voters are increasingly turning to the “left.” Meanwhile, less educated voters, along with richer voters, are turning to the right.

But Canada isn’t like other countries since we don’t have a standard left-right party system. Instead, the Liberals have dominated electoral politics as an amorphous party at the centre of the political spectrum — sometimes shifting to the left, sometimes to the right — that always builds a big tent in the middle.

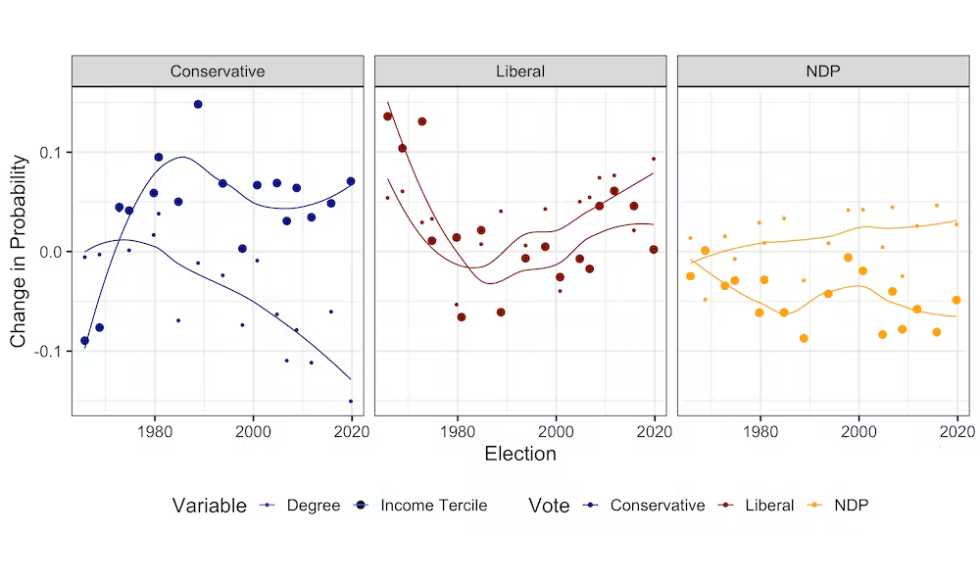

Analyzing these parties’ support separately shows that they have very different bases of support. The graph below shows the effects of the same variables (education and income) but broken out by party.

A different pattern emerges in this graph. While Liberal and Conservative support fits Piketty’s pattern, the NDP is increasingly attracting support from educated but also poorer voters.

Sources of division

What are we to make of all this?

With this long view, ongoing societal conflicts since the 1980s about abortion and same-sex rights take on an outsized significance.

Those issues were major sources of division among voters choosing between the Liberals and the Conservatives. The current divide over transgender rights is just the latest episode in the long trend of educated voters increasingly supporting the Liberals (and sometimes the NDP) with less educated voters increasingly supporting the Conservatives.

However, people concerned with economic redistribution should not despair. Redistributionist politics are not absent from this configuration, particularly in the form of the NDP. For all the talk about a new “woke” NDP, its base is increasingly dominated by poorer voters.

In the supply and confidence agreement the NDP signed with the Liberals, four of the seven policy points were explicitly about material gains for workers. This included a transformative dental benefits plan for all Canadians.

If culture war conflicts benefit Liberals and Conservatives in terms of the differences in education, the agreement shows how delivering redistribution is central to the NDP’s electoral ambitions, especially amid an ongoing cost-of-living crisis.

The so-called “diploma divide” we identified is going to ensure that cultural and social conflicts will persist indefinitely and will continue to cause political conflict in Canada.

But material and redistributionist concerns are in the mix as well, assisted by the NDP, a social democratic party that is very different from the other “left” party, the Liberals.![]()

Simon Kiss, Associate Professor Human Rights and Political Science, Wilfrid Laurier University; Matt Polacko, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Political Science, University of Toronto, and Peter Graefe, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.