Analysis: It’s time to abolish Canadian law that allows adults to spank and hit children

Strategies that may help reduce support for corporal punishment — as well as reduce its use and intentions to use it — include individual and group-based programs to develop positive parenting skills. (Shutterstock)

BY Tracie O. Afifi, University of Manitoba; and Andrea Gonzalez, McMaster University

April 19, 2023

Corporal punishment (e.g., spanking) is allowed in Canada according to Section 43 of the Criminal Code of Canada. Some Canadians are not aware of this and are surprised to learn that such a law exists, whereas others want to hold onto this archaic act.

A growing number of Canadians, however, are aware of the law and understand the need to have Section 43 abolished. The real question is why hasn’t our country already removed permission to hit children from the Criminal Code of Canada?

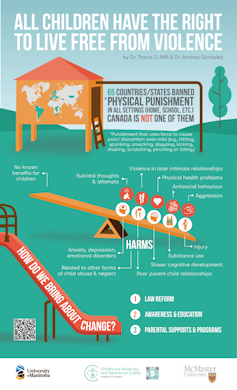

Globally, efforts to end violence against children, including corporal punishment, have been underway for half a century. To date, 65 countries and states worldwide have banned corporal punishment. Unfortunately, Canada is not one of them.

Currently, Bill S-251, which would ban corporal punishment in Canada, is being debated in the Senate. Now is the time to provide evidence to Canadians to inform the debate.

Why corporal punishment should never be used

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child defines corporal punishment (also referred to as physical punishment) as punishment that uses physical force that is intended to cause pain or discomfort even if it is very mild or light. Corporal punishment can include hitting, spanking, smacking, slapping, kicking, shaking, scratching, pinching or biting, among other physical acts.

Canadian estimates within the last 10 years suggest that between 18 per cent and 43 per cent of families use spanking to discipline children.

Evidence collected over the past two decades and published in hundreds of peer-reviewed studies, has demonstrated that corporal punishment is harmful to children and has no known benefits.

This research has consistently shown corporal punishment to be a significant risk factor for injury, poor parent-child relationships and poor outcomes in children and youth. These include aggression, antisocial behaviour, slower cognitive development, emotional disorders including anxiety and depression, physical health problems, substance use, suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts and violence in intimate relationships later in life.

Because of serious concerns about the significant negative outcomes associated with corporal punishment, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a statement in 2018 clearly recommending against any physical punishment, including spanking, hitting and slapping. A similar statement was published in 2019 by the Canadian Paediatric Society:

“At no time should parents use physical punishment — spanking, slapping, hitting — or behaviour that shames children.”

Barriers to repealing Section 43

Extensive evidence highlights the harms of spanking, and no studies have found any benefits of spanking for the child. Sixty-five other countries or states worldwide have already instituted spanking bans. The question remains: Why hasn’t Canada already repealed Section 43 of the Criminal Code?

A common argument for spanking is, “I was spanked, and I turned out OK.” While that may be true for some people, it often isn’t the case.

Many children, youth and adults experience numerous poor outcomes across their lifespan related to being spanked in childhood. Physical punishment in childhood is associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect and/or exposure to intimate partner violence.

It’s clear that spanking is a parenting strategy that comes with significant and unnecessary risks.

A common misconception related to the repeal of Section 43 is that laws banning corporal punishment will mean criminalization and incarceration of parents. This is simply not true and not the purpose of a ban.

In 1979, Sweden became the first country to ban corporal punishment in all settings; the aim was to educate the public — not prosecute parents. Prosecution rates of parents remained unchanged after the ban was in place.

The overall purpose of such bans is to reduce the use of corporal punishment, increase early identification of at-risk children and youth and to support families through preventive interventions.

Evidence of changing public attitudes

Several strategies have shown promise in reducing support for corporal punishment, as well as in reducing the intention to use, and the actual act of using it. These include individual and group-based programs to develop positive parenting skills, home visitation programs and media-based interventions.

Some studies have also demonstrated that providing research summaries about harms related to corporal punishment and information about children’s rights can help parents to decide to stop spanking.

Importantly, research from several countries indicates that legislation prohibiting corporal punishment may be the most effective method of reducing public support for the use of corporal punishment. Bans alone may not be sufficient; they should be enacted in combination with public awareness and education campaigns.

It is essential that Canada complies with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child that prohibits spanking. It is our duty to protect our children from unnecessary harm and give them the best chance to live happy and healthy lives that are free from violence. This starts with the Repeal of Section 43.![]()

Tracie O. Afifi, Professor and Canada Research Chair in Childhood Adversity and Resilience, University of Manitoba and Andrea Gonzalez, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.