Analysis: Rising Canadian patriotism is a chance to rethink who gets to belong here

Blueberry Grunt performs at the Elbows up rally at Alderney Landing in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia on April 6, 2025. (Riley Smith, The Canadian Press)

BY Alpha Abebe

April 21, 2025

![]() Alpha Abebe is an associate professor in the Faculty of Humanities. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Alpha Abebe is an associate professor in the Faculty of Humanities. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Some Canadians are pushing back against recent threats from the United States government to Canada’s sovereignty and economic stability with the rallying cry “Elbows up!”

Borrowed from hockey, the phrase charges Canadians to raise one’s elbows in preparation to fight back.

In another gesture towards Canadian national solidarity, the iconic 2000 “I am Canadian” beer ad was recently revived by the ad’s original actor, Jeff Douglas.

The video, We Are Canadian,, includes familiar Canadian symbols, from hockey games to peacekeeping missions and Canadian flags. As others have observed, these trends are emblematic of a dramatic spike in Canadian patriotism.

The desire to rally behind symbols of unity is understandable in precarious times. However, it is also a good time to consider who and what is being obscured behind this version of Canadian patriotism.

As the U.S. institutes increasingly racist, xenophobic and authoritarian policies, this moment may be just the warning Canadians need to imagine a more just, grounded country. Which direction we walk will depend on some important considerations.

Canada is constantly changing

As a scholar of migration and diasporas, I take note of changes to the Canadian population.

It’s grown significantly more diverse in recent years. But dominant discourse about Canadian nationalism often flattens these realities, invoking multiculturalism while failing to engage with deeper histories and contemporary realities.

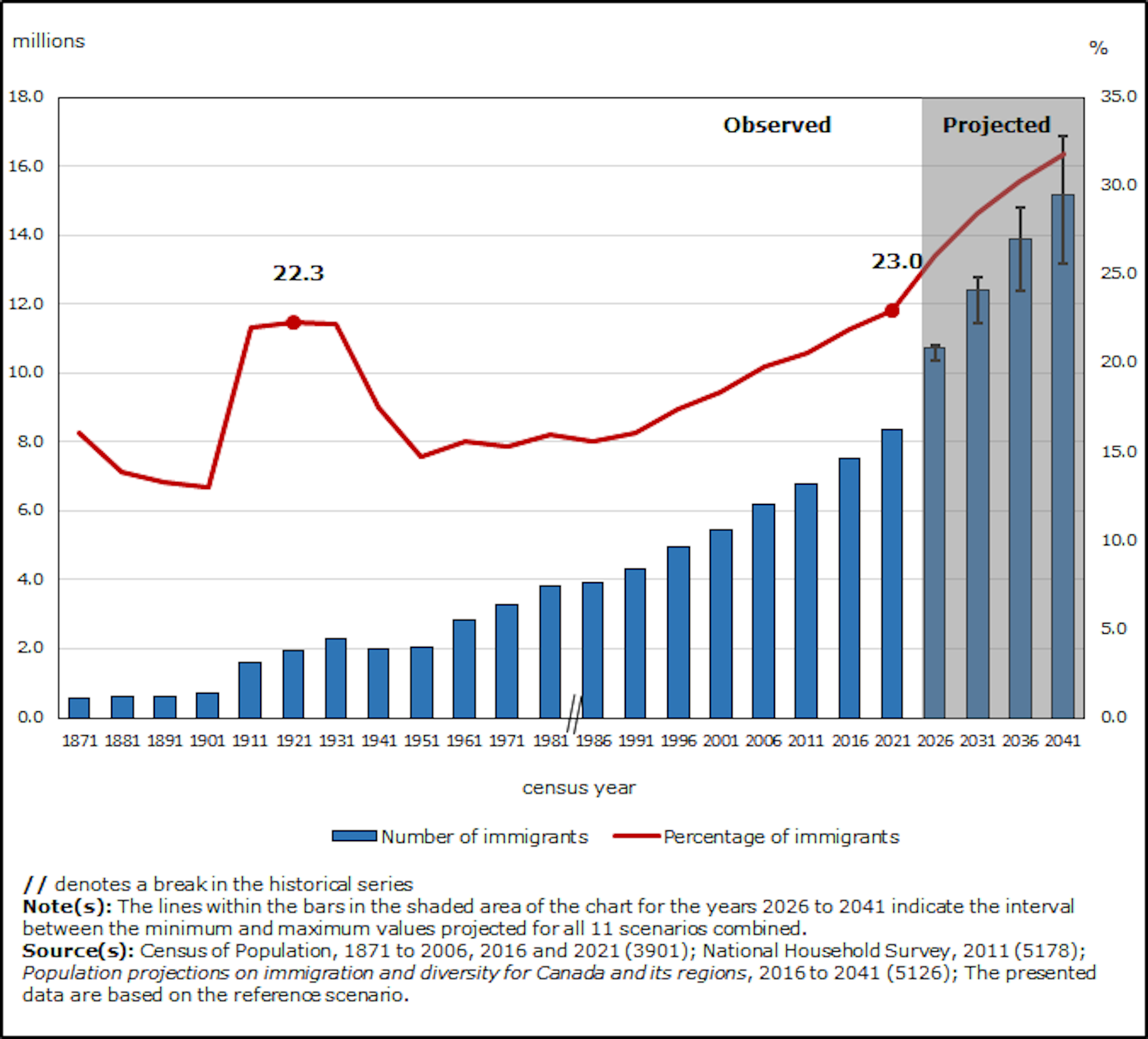

For example, Black diasporas are one of the fastest-growing segments in Canada. And almost 25 per cent of people in Canada are immigrants.

The racialized population in Canada accounts for about 26 per cent of residents, about double the number recorded in 2001. According to most projections, half the Canadian population will be made up of immigrants and their Canadian-born children by 2041.

These shifts reflect long-term immigration reforms, especially those beginning in the 1960s, when the federal government moved away from “White Canada” policies that explicitly excluded non-European immigrants.

Today, many people in Canada — Indigenous, immigrant, Canadian-born — maintain complex relationships to settler colonialism, as well as multiple homelands, cultures and histories.

Yet popular narratives of “Canadianness” can be narrow and out of step with the experiences of diverse segments of the population. Scholars Lloyd L. Wong and Martine Dennie point out that the idea of Canada as a “hockey nation” is sometimes contested by communities marginalized by the sport’s ties to anglo male dominance.

In their book Unsettling the Great White North: Black Canadian History, historians Michelle A. Johnson and Funké Aladejebi argue that the Canadian narrative reflects a historical and ongoing systematic erasure of Blackness.

Youth discomfort with nationalism

In my teaching and academic leadership roles, I engage with young people and aim to centre their voices in reimagining our institutions and communities. Through this work, I have the privilege of listening as young people reflect on their perceptions of Canada and desires for its future.

Many of my students express discomfort with unabashed nationalism, identifying instead with their local and regional cultures, and gravitating towards abolitionist ideals such as demilitarized borders and migrant solidarity.

The ongoing work of truth and reconciliation

There is also a growing desire among the young people I teach to reconcile their profound lack of formal education in Indigenous histories, ideas and issues.

Even in our resistance to external threats, we must remain committed to addressing the internal legacies of colonial violence, as outlined by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and its framework for healing.

The TRC provides a road map for the critical work of bridging gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, as led by Indigenous leaders and organizations.

The recently published book Deyohahá:ge: Sharing the River of Life features chapters written by members of Six Nations as well as non-Indigenous neighbours, indicating a need for dialogue. The book reflects on the Two Row Wampum Agreement and how these agreements might restore good relations today.

In another example, Black Canadian artist Jully Black altered the Canadian national anthem to acknowledge our colonial history, singing “our home on native land,” instead of our home and native land during the 2023 NBA All-Star Game. Her performance generated critical conversations about Canada’s national narrative.

Scapegoating

Part of the Canadian identity story is about being a welcoming nation. But Canadians have long scapegoated newcomers as being to blame for a host of issues.

We see this play out in immigration policy and political discourse. For example, the Liberal government’s recent cuts to immigration levels was framed as a response to housing and economic pressures.

The Conservative Party has also portrayed immigrants as burdens on housing and infrastructure while stoking fears about “criminal” and “bogus” migrants.

Similarly, in the final stretch of his 2015 campaign, Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government leaned into xenophobic rhetoric, most notably with the promise to establish a “barbaric cultural practices” hotline which was being positioned as a defence of “Canadian values.”

Fresh perspectives on Canadian identity

Canada is often criticized for having a weak or reactive national narrative defined more by what it is not (the United States) that by what it is.

But distancing ourselves from American crises doesn’t excuse us from confronting our own contradictions. This moment of heightened patriotism demands more than just symbolic unity.

My students increasingly challenge shallow notions of multiculturalism, pushing instead for structural change that is material, not just rhetorical.

Their critiques reflect wider public conversations: youth-led panels, academic research and lived experiences that question the limits of inclusion without equity. They are asking: Who benefits from these patriotic myths? Who gets erased?

To move forward, Canada must build a collective story rooted in truth — not just selective nostalgia. One that honours Indigenous sovereignty, confronts contemporary inequities and reflects the rich diversity of its people. Only then can we begin to imagine a future Canada worth rallying behind.![]()

Alpha Abebe is an associate professor in the Faculty of Humanities. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.