Analysis: The Electric City is a better way to make cars

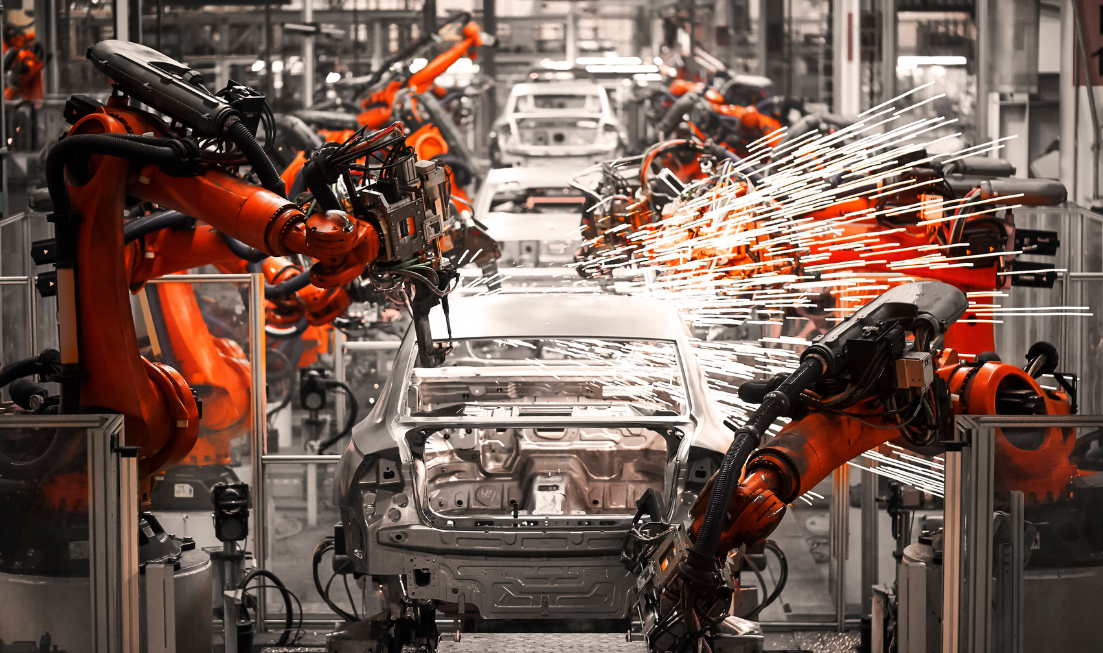

There's no reason we can’t reinvent the way we make cars, writes professor Ali Emadi. The Electric City project — a nod to Hamilton's industrial past and exciting future — will bring together industry, government and academic partners to build cars with a simpler, more localized process. (Adobe image)

BY Ali Emadi

May 28, 2025

Creating a new product and moving it through manufacturing to the marketplace is a massive and daunting undertaking.

In the case of a car — the most expensive, complex manufactured item most consumers will ever buy — it typically takes an automaker as long as three years and close to $1 billion to get a new model ready to manufacture.

Every car on the road is the product of a cycle that includes design, development, integration, prototyping, testing, calibration and, finally, mass manufacturing.

The design and development process involves hundreds, even thousands of engineers and other qualified personnel. All their work is aimed at making that new car in a factory built specifically for that purpose.

The expense is so huge that the only way to recoup the investment is by making huge quantities of that new vehicle and selling them in multiple markets, typically over several years, with only minor annual updates before it’s time for a makeover of the model and the plant where it’s built.

That’s the way the industry has been doing it for the last century, but if the automobile were to be invented today, it’s not how we would do it.

We’d rely heavily on digitization techniques and use a combination of digital technology and physical testing to reach the point of manufacturing much more quickly.

We’d incorporate human feedback into the virtual development of a component, system or vehicle prior to prototyping, in a concept we call drive-before-build.

Ultimately, we’d make smaller batches of cars and the components that go into them by designing flexible manufacturing platforms, and we would sell them closer to the points where they’re made.

A thoroughly modern, far less expensive design and development process would not require hundreds of thousands of copies of a single model to be made before a manufacturer could recover its costs.

As automotive technologies such as electric motors, power semiconductors and converters, batteries, controls, and lighter-weight materials evolve, manufacturing technology and processes should be changing in tandem to shrink the long timeline between concept and market, and to create modern factories that can move nimbly between makes and models, saving manufacturers and consumers money in the process.

There is no reason we can’t reinvent the way we make cars, and we’ve already started engineering the change in Hamilton. We call our project the Electric City, reviving an old nickname for Hamilton from the days before it was called Steel City or the Hammer.

At the turn of the 19th century, when electric streetlights, interior lighting and power to run factories were novel, Hamilton, being an industrial centre close to the new hydroelectric facilities at Niagara Falls, became an attraction that drew outsiders to see what an “Electric City” would look like.

The availability of low-cost electric power drew manufacturers and prosperity. George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla — who had collaborated on the Niagara Falls power project — set up their first Canadian factory operation on Longwood Road South in Hamilton’s west end.

The same site is now home to the McMaster Automotive Resource Centre (MARC), where researchers invent and test new technology for cars, both independently and in direct partnership with major auto makers, whose experts are embedded with university and government researchers and students.

While we continue with that work, we’re also planning a major makeover for the whole process of making new cars.

The major hurdle is resolving the design bottleneck that chews up so much time and so many resources, and which ultimately impedes innovation by loading huge economic risk into any single model.

We know there’s strong appetite for change across the industry, and we’re delivering it through a model that will benefit manufacturers and consumers alike, with a non-profit Electric City corporation featuring a for-profit, public-private arm that can create new jobs and better, more affordable vehicles.

The new Electric City — the word “electric” here is used to mean “exciting” — would harmonize some key pre-manufacturing processes among major manufacturers.

They’d still be competing against one another and still independently produce distinct vehicles, but they could all prepare them for production by following a common process and a common manufacturing platform.

Doing such work in Canada makes economic sense, where a lower dollar and the availability of public health care make engineering costs lower than they are in the U.S., and — so far, at least — there are no tariffs on design and development work.

At MARC, we have much of the very sophisticated equipment manufacturers use for testing cars and their components, which is why major automotive companies are already using the facilities at MARC.

That gives us a big head start for taking the next steps to become an international design and development hub, possibly with major new construction and additional equipment that automakers would no longer need to buy.

Soon we’ll be able to move much of the physical testing that happens today to the digital domain, where in-house engineers specializing in every aspect of auto manufacturing can test, refine, and optimize versions of components and whole vehicles without ever having to build anything physically until it’s time to roll out next-to-final prototypes.

Much of the design and development work that’s performed sequentially today could be done simultaneously, collapsing the timeline from years to months.

Today, everyone in the industry is understandably worried about a trade war. We can turn uncertainty to advantage by creating new opportunities in the automotive industry and expanding them as conditions improve.

We can design vehicles for today and tomorrow and make our corner of the world more attractive than ever as a place to build them, using a simpler, more localized process.

Bringing together industry, government and academic partners, we can re-invent the way cars are made, right where the market is.

Professor Ali Emadi is the Canada Excellence Research Chair (CERC) Laureate and holds the NSERC/Stellantis Industrial Research Chair in Electrified Powertrains and Tier I Canada Research Chair in Transportation Electrification and Smart Mobility. He is the founding president and CEO of Enedym Inc. and founder of MenloLab Inc.