Analysis: Why can’t we die at home? Expanding home care could reduce the financial and environmental cost of dying in hospital

Most patients would rather spend their final days at home, but there aren’t enough community care resources to care for them at home. (Shutterstock)

BY Myles David Sergeant

November 19, 2024

![]() This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Where would you like to be when you die? Seven out of eight people in Canada would choose to pass away at home where they and their loved ones would be more comfortable.

And yet 56 per cent of people in Canada actually die in hospitals.

If dying at home could be made more feasible and well resourced, both the dying and the living would benefit.

First and foremost, it would be more peaceful and consistent with what we value. A community-based palliative approach keeps our values, goals and dignity at the core of care.

Secondly, whether you’re in an early, middle or late stage of life, staying in hospital is extremely expensive. A single bed in a Canadian hospital costs about $1 million a year to operate, so we have to use each one judiciously.

Finally, we could help reduce health care’s massive environmental impact. If health care were a country, it would be the fifth-largest producer of carbon emissions in the world, responsible for 4.4 per cent of the global total.

The high cost of hospitals

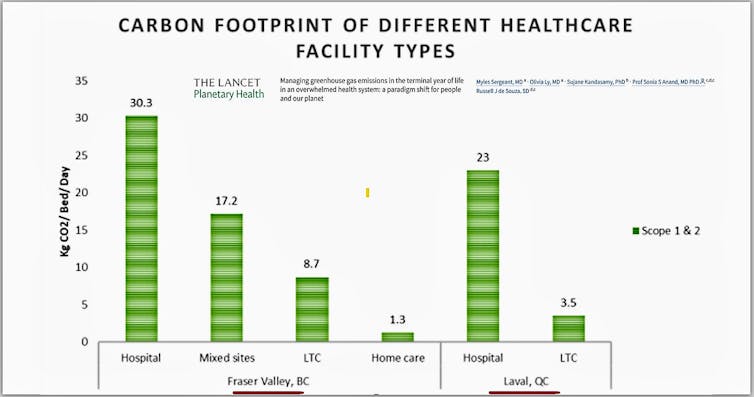

An article my colleagues and I wrote for The Lancet points out that providing end-of-life care in a community setting, such as home care, uses much less greenhouse gas. Hospitals draw disproportionate amounts of energy for ventilation, heating and equipment, and they use more disposable supplies.

One patient’s day of hospital care generates an estimated 30 kilograms of greenhouse gas, compared to eight kilograms for long-term care and just two kilograms for home care.

Almost all of us need to spend some time in a hospital at some point in life, whether it’s when we’re born, giving birth or being treated for an injury or illness. By far, though, the greatest amount of time most of us spend in hospital is in the last year of our lives, whether that time comes in our 40s or our 90s.

The medicalization of death

A typical person’s use of the medical system rises very gradually with age, but in the final few months, it increases rapidly as we turn to the hospital system and the resources that come with it.

This reflects what some refer to as the “medicalization of death.” A palliative medicine physician in the United Kingdom, Dr. Libby Sallnow, has summarized this succinctly:

“How people die has changed dramatically over the past 60 years, from a family event with occasional medical support, to a medical event with limited family support.”

Certainly, those who need complex pain management or other special care should receive it in the setting that best suits their needs, which is often a hospital.

But of all the people in a typical Canadian hospital — and we are not alone in this situation — about one in six are not even benefiting from being there.

In my own practice, which includes working in a complex care facility in Hamilton, Ont., there are typically many patients who have been medically approved for an alternative level of care, or ALC, meaning they could return home or be placed in a long-term care facility.

And yet, even though most patients would rather spend their final days at home, we have difficulty sending them there, because there aren’t enough community care resources to care for them at home.

Care at home

We need dedicated home-care teams that can provide care in line with patient wishes. Important components of home care include: an integrated team, proactive care, management of physical symptoms and caring and compassionate providers.

Primary-care teams can act as informal managers of home care through facilitating the medical, social and comfort components of care. All of this would still add up to far less than the financial and environmental cost of hospitalization.

At a time when we’re pressured to cut costs and reduce harm to the environment, and when we know dying patients would rather be at home, why can’t we help?

Places like Germany make it easier by paying family caregivers to look after patients at home, reducing the financial barrier that keeps many people in hospital.

The experts in gerontology and epidemiology who direct the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging advocate for planning communities with home-based and neighbourhood-based care in mind, making care both more humane and efficient.

A family medicine colleague, Dr. Henry Siu, is investigating ways to reduce the number of long-term care patients who are mistakenly transferred to hospital because of misunderstandings related to consent.

These and other ideas are available if we want to take advantage of them.

Meanwhile, though, we keep building or expanding hospitals, following the same puzzling and counter-productive logic that causes us to widen roads and highways instead of finding better ways to get around.

This month, I will be representing McMaster University Planetary Health in the COP29 climate conference in Azerbaijan. Within the sustainable health sector at COP, the end of life is a topic that is rarely discussed, but it needs to be.

Myles David Sergeant, Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Family Medicine, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.