Canadians are rightly worried about invasion of privacy in smart cities

Smart planning of cities needs to include addressing citizens’ privacy concerns. (Photo by Shutterstock)

BY Sara Bannerman

February 7, 2019

In January 2019, Liberal MP Adam Vaughan argued that privacy concerns about the smart city proposed for Toronto’s waterfront should not be allowed to “reverse 25 years of good, solid work and 40 years of dreaming on the Toronto waterfront.”

But a recent survey suggests that Canadians have strong concerns about giving up on 50 years of struggle for privacy rights so that Google’s sister company, Sidewalk Labs, can establish a smart city in Toronto.

A national survey we conducted at McMaster University found that 88 per cent of Canadians are concerned about their privacy in smart cities, including almost a quarter (23 per cent of Canadians) who are extremely concerned.

Public data, private citizens

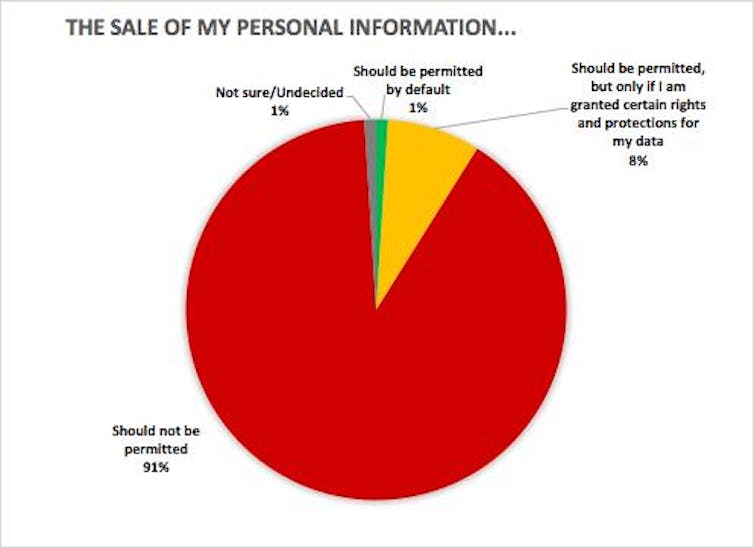

Some smart-city projects are led by municipalities, whereas others are led by businesses. We found that Canadians object more strongly to private and for-profit uses of their personal information. Our survey revealed that 91 per cent of Canadians think that the sale of their personal information should not be permitted. Sixty-nine per cent do not think the use of their personal information to target them with ads should be permitted.

Canadians are more open to public uses of their data. Many (71 per cent) were open to the use of their data for use in traffic, transit or city planning. Many (63 per cent) were open to the use of their personal data by police in crime prevention.

However, a quarter of Canadians do not think that the use of their personal information in traffic, transit or city planning should be permitted at all, and a third of Canadians do not think that the use of their personal information by police in crime prevention should be permitted. This sentiment is even stronger among visible minority and Indigenous participants.

Many current smart-city projects are far out of step with Canadians. The proposals for a smart city on Toronto’s waterfront are driven by Google’s for-profit sister company Sidewalk Labs.

While Sidewalk Labs has committed that the data collected through the project will not be sold nor used for targeted advertising by default, Google’s record on privacy is blemished by revelations that it tracked location data for individuals who had explicitly turned off location tracking. It was recently revealed that Sidewalk Labs now plans to sell location data to cities.

Consent as a sham

Many smart-city projects do not conform to Canadians’ wishes on control of their data. Although Canadians strongly object to the sale of their data, even if rights and protections are in place, the sale of data is currently legal if users give consent.

This consent is a sham, typically obtained through policies that users never read before they click “I Agree.”

Most Canadians who expressed openness to the use of their personal information for public uses did so on condition that they would have certain rights and protections — rights and protections that they often do not currently have, at least in practice.

Most of all, Canadians want their data to be used in aggregate so that they’re not personally identifiable. But many smart-city projects — especially those that make use of location data — may leave individuals exposed, because location data is highly individual and easily re-identifiable.

Many Canadians want the right to opt out, opt in, view, delete, download and correct their data. A large majority of Canadians strongly agreed that they should have the right to view the personal information that has been collected about them (80 per cent).

A majority of Canadians also strongly agreed that they should be able to delete that data (66 per cent), as well as download it (65 per cent). Many smart-city initiatives do not afford these options. Can you delete, download, or correct your transit use data? When a mall directory uses facial recognition technology, or a city purchases cellular location data, or your transit company passes your data to police, can you opt out?

The survey suggests that Canadians are not satisfied with the current model of notice and consent which often leaves only two options: agree with a privacy policy, or don’t use the service.

Canada needs to up its game on privacy and data control, given the growth of efforts to establish new, often privacy-invasive, technologies in Canadian cities and municipalities.

Sara Bannerman, Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in Communication Policy and Governance, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.