Coronavirus ‘cures’ for $170 and other hoaxes: Why some people believe them

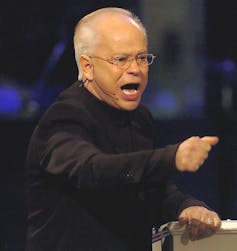

FOX News host Sean Hannity (pictured here in 2018) gave credibility to a tweet he read out lout on his popular syndicated radio show, which called COVID-19 a fraud “to spread panic in the populace, manipulate the economy and suppress dissent.” AP/Julie Jacobson

BY Jeremy Cohen

March 24, 2020

As the world continues to deal with the life-altering effects of the novel coronavirus, a small but not-insignificant number of individuals have been expressing their fears about COVID-19 through the language of government conspiracies and wild alternative health cures.

Last week, one online conspiracy network suggested that COVID-19 is an act of biological terrorism to attack Chinese trade. Last month, a popular online site said the virus was a hoax manufactured to induce global fear and would therefore be a boon to Big Pharma. A website based in Toronto claims COVID-19 is the result of 5G cellular networks plus the common cold.

Press TV, part of the state sponsored media in Iran, suggested “Zionists” were behind the spread. As recently as last week, some public officials in the United States government continued to underplay the seriousness of the virus.

As reported by the New York Times, popular conservative talk-radio host Rush Limbaugh called the virus a “plot by the Chinese,” and conservative commentator and FOX TV host Sean Hannity read and gave credibility to a tweet calling COVID-19 a fraud “to spread panic in the populace, manipulate the economy and suppress dissent.”

Why have conspiracy theories so readily circulated during the COVID-19 pandemic? What type of person believes medical conspiracy theories?

I research new religious movements. I decided to explore this question because of the ubiquity of conspiratorial thinking within some of these communities. What can belief in alternative theories tell us about ourselves?

What challenges might conspiratorial thinking, circulated online and in popular media, present to public health advocates in the coming year?

Conspiracy in the age of coronavirus

Conspiracy theories connecting the COVID-19 pandemic to the state of Israel are flourishing. One source, part of a large global conspiracy community, claims the novel coronavirus is an act of Israeli bioterrorism.

Jews have historically been blamed for global viral events, including the Black Death in the 1300s, which led to massive pogroms against European Jewry. The common narrative goes that people in the Middle Ages needed a scapegoat because they did not know about the germ theory of disease. However, 130 years after Russian microbiologist Dmitri Ivanovsky and Dutch scientist Martinus Willem Beijerinck (working independently) discovered the existence of viruses, Jews continue to take the brunt of conspiratorial blame.

Hoaxes in alternative medicine

Infowars’ Alex Jones claimed a product called DNA Force Plus could help fight off COVID-19: it is currently on sale for US$89.95 for one month supply. Another popular supplement advocate suggests a cocktail of over 11 different supplements to combat coronavirus, costing over US$170 a month. Other purported cures include vitamin C dosing, faith healing and homeopathic vaccines. There is no evidence that any of these work.

As demand for alternative medicine grows, Canadian researchers recently looking at internet health scams found, most of the alternative products marketed online “either severely misrepresented the efficacy for the given health concern and/or had no strong scientific evidence‐base to support their use as advertised.”

Since being declared a global pandemic, there is evidence that demand for alternative medicine has increased. Some alternative medicine has been shown to be effective, but many of the options being marketed today have not. As Timothy Caulfield professor of health law at the University of Alberta writes: trust in science is crucial right now.

Who believes in conspiracy theories?

Conspiratorial thinking can be founded on legitimate concerns and transcends socio-economic, racial, educational and gender boundaries. This complicates our tendency to view conspiracies as perpetuated by tinfoil-hat wearing people.

A number of theories have been proposed to account for conspiratorial thinking.

University of Chicago political scientists Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood explored medical conspiracy theories. They found approximately 50 per cent of Americans believe in at least one general conspiracy theory, and more than 18 per cent believe in three or more medical conspiracies.

Writing in the Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, Oliver and Wood wrote:

“Although it is common to disparage adherents of conspiracy theories as a delusional fringe of paranoid cranks, our data suggest that medical conspiracy theories are widely known, broadly endorsed and highly predictive of many common health behaviours.”

Perhaps the explanation for the broad appeal of such theories points to something more fundamental to the experience of being human? When people talk about quarantines, hoarding and conspiracies, they can ignore the elephant in the room: death.

Research suggests that we use different management techniques to deal with the terror of death. Where sickness can act as a reminder of our finitude, simple health-management solutions can offer a sense of autonomy over our bodies.

This may explain why some conspiracy websites are downplaying the danger of COVID-19 to adults by focusing on the older age of the victims. In other words, pandemics are scary, and they remind us that we are mortal.

Even if medical conspiracies are mostly confined to the fringe, the effects of conspiratorial beliefs on public health may end up exacerbating the spread of the virus. People may continue to ignore quarantine orders. A future vaccine for COVID-19 may come up against a growing anti-vaccine movement. Will people continue to be receptive to anti-vaccine conspiracy rhetoric in the age of COVID-19?

Conspiracy theorists, like all of us, are trying to make sense of a complicated world. Having a sense of control against an ineffable source of power — which describes the novel coronavirus in many ways — may speak to some of our collective fears and motivations in the face of mortality. After all, nothing offers direct evidence of human finitude and frailty like a viral pandemic.![]()

Jeremy Cohen, Doctoral Candidate, Religious Studies, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.