‘You build trust by showing up over a long period’ — Daniel Coleman on allyship and privilege

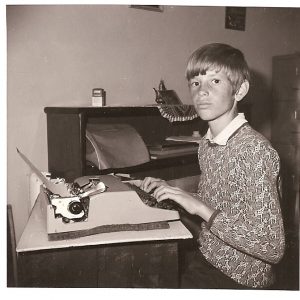

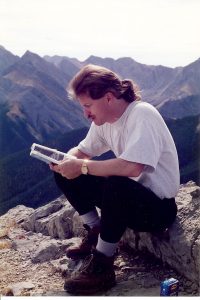

Daniel Coleman at Fall Convocation

BY Sara Laux, Faculty of Humanities

December 15, 2023

At the Fall 2023 convocation ceremony, Professor Daniel Coleman from English & Cultural Studies was named a Distinguished University Professor, one of three people to receive the honour this year.

This recognition is given to McMaster faculty who have demonstrated research that has achieved international impact and recognition, exceptional work in teaching and learning, and service that has made a difference to the community.

Coleman, who came to McMaster in 1997, is the author of several books, including Masculine Migrations: Reading the Postcolonial Male in “New Canadian” Narratives (1998), The Scent of Eucalyptus: A Missionary Childhood in Ethiopia (2003), White Civility (2006), which won the Raymond Klibansky Prize from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, In Bed With the Word (2009), and Yardwork: A Biography of an Urban Place (2017), which was a finalist for the RBC Taylor Prize.

Along with colleague and fellow ECS professor Lorraine York, Coleman is the co-director of the Centre for Community-Engaged Narrative Arts (CCENA), which, according to their website, supports “arts-based community listening, remembering and story-making,” connecting community members “with other communities, media and sources of expertise to support them in telling their stories.”

He has also been active in equity, diversity and inclusiveness efforts throughout his career.

Here, Daniel Coleman shares some thoughts about his time at McMaster, his childhood, the role of an ally, and his approach to writing.

How did your childhood in Ethiopia affect the work you’ve done as an adult?

I grew up in some of the classic categories of privilege: whiteness, masculinity, part of the dominant culture in Europe and North America – but because I was in Ethiopia, that was actually outside of the local norm.

I grew up knowing that the way I perceived the world was limited to my culture, and that there were ways people lived outside my perspective that had impressive coherence and power.

I was aware of moving between cultures – when I moved to Canada, I wasn’t exactly an immigrant, because I was a Canadian who grew up outside of Canada. I already had a passport and didn’t have any legal difficulties, but the cultural assumptions in Canada were just…not self-evident. It was very different from how I grew up.

When I went to go to university, it became intuitive to think that university ought to be a place where lots of kinds of knowledge meet each other, and have the equal capacity to influence each other.

If I were to give the way I grew up a name now, it would be an ecosystem of interrelating knowledges, multiple ways of seeing the world. I didn’t have that language when I was a kid.

As someone who does occupy many categories of privilege, how do you approach doing work in equity, diversity and inclusion?

I’ve had students ask why a white guy is teaching a class on critical race studies, and for good reasons – they’re distrustful. People like me who inhabit the social norms are often oblivious. For example, I don’t live in the everyday of having the police stop me because I’m in the wrong neighbourhood, for driving while Black or Indigenous – so the normality of everyday life is structured by my not knowing things, by structured obliviousness.

That’s why, to me, we need contact with people who live in different paradigms than ourselves, so we learn more about the world, and know that these experiences are in the world we inhabit. I need to be in those partnership/allyship kind of relationships to even see the world at all.

But there’s a long history of people from categories of privilege speaking on behalf of others – through the idea of humanitarianism, charity, or benevolence – doing things on other people’s behalf without being aware of our own privilege and replicating the relationships that created those inequities in the first place.

I have to remind myself that if people don’t trust me, there’s a good reason – I didn’t make that history myself, and it’s not just about me, but I’m the local representative of that long-term history.

I need to keep alert to that and understand that when there’s pushback, there’s a good reason for it, and try to learn from it. The only thing you can do is work to build trust, and trust takes time – people need to see that your actions support the proclamations you make.

How do you build that trust?

You need to commit to long-term relationships, not just the length of a project – you build trust by showing up over a long period.

Others have been patient and gracious with me as I’ve tried to follow their lead – like my Indigenous colleagues who, back in the day, were trying to see where a university life could take them and came to ask whether I would supervise their dissertation. That was an indication of a certain amount of trust, but I needed to live up to it.

That idea of following someone’s lead seems to be a common thread in a lot of the work you do.

Following the lead is key to all these kinds of relationships, I think, and it’s basic to learning – if you are going to learn anything, you have to have enough consciousness of need or emptiness in your mind to welcome something in. If it’s already full, and you think you’ve already got what you need to know, then why would you listen to anything?

You learn from the relationships that you’re in.

Back in 2010, I was asked to teach in the Discovery Program. Now, you could look at a program like that, which is a free class for people who had barriers to postsecondary education, as an act of benevolence by the university, dispensing its knowledge to people who have not had access to it.

But what I learned in the classroom was how resourceful people living close to the street could really be, and how much analysis they had to offer, and how many rich stories they had to share about life in Hamilton.

It made me feel like the university can be a place that sees the value of the kinds of knowledge people carry with them, and we can provide ways of respecting and amplifying and providing platforms for that.

You’ve done a lot of writing, both academic and for a more general audience. Tell me about that drive to share your work with a wider readership.

I’ve felt that if you’re learning and writing towards visions of what society could be, then it’s important to speak to society – not just other scholars who are thinking your same thoughts and only publishing in places that other scholars will read.

The public writing part seemed to me to be a way to take the privilege of learning and reading and thinking – because not everybody gets to do that – and say, “How can I make these topics relevant and useful to people who DON’T get to do that?” I think it taught me to be a much better writer, if nothing else.

The public writing part seemed to me to be a way to take the privilege of learning and reading and thinking – because not everybody gets to do that – and say, “How can I make these topics relevant and useful to people who DON’T get to do that?” I think it taught me to be a much better writer, if nothing else.

Indigenous relations, race relations, or ecological relations, all of which I’ve written about, are questions that are burning for so many people – so I feel like there’s a relevance to these public conversations that I am interested in and energized by.

What are you working on right now?

I’m finishing two book projects right now: one is a collection of essays I’ve edited with Haudenosaunee co-editors based at McMaster, Ki’en Debicki and Bonnie Freeman. It’s a gathering of essays by mostly Grand River writers on the Covenant Chain-Two Row Wampum tradition, from its history to its present application.

I can’t wait for that book to come out – it’s such a powerhouse of amazing thinking and interesting context!

I’m also writing my own book on the same topic. The essay collection is a way of showing the ferment of thinking and action, and the community of knowledge out of which my own writing comes – it comes from that kind of conversation and dialogue.

Can you share a little about your approach to teaching?

That too has been a learning experience.

When I started teaching, I had these models in my mind based on the ways I had been taught – they were good models, because they cared about helping students engage, whether it was with literary texts or cultural moments, and to learn how to think for themselves outside of just normative frameworks.

But from experiences like the Discovery Program, and, really, the lovely McMaster tradition of inquiry and problem-based learning, I’ve also learned to create courses that gave students ways of designing their own problems and write or create their own way into addressing them.

What does being named a Distinguished University Professor mean to you?

I keep hearing EXTINGUISHED University Professor in my head, to be honest!

There are lots of other folks who do good research and teach great classes. I’m reminded of the time when my friend and colleague Lorraine York was nominated to the Senator William McMaster chair, and she said she’d accept the role as long as they called it the Senator William McMaster COUCH – so everybody could sit on it together.

And I’m so honoured that my colleagues have seen something of value in the work I do – that’s a beautiful thing, and I’m deeply appreciative.