Dear Bertie: Letters to Bertrand Russell

An online exhibit is showcasing some the letters written to peace advocate, philosopher and Nobel laureate Bertrand Russell by some of the most recognizable figures of the 20th century. Russell’s archives – the largest collection of Russell materials in the world – contains more that 130,000 letters, 250,000 original documents written by Russell, 3400 books from his personal library, 3900 volumes of his published works and other scholarly materials, as well as many photos and artifacts including his 1950 Nobel Medal in Literature.

BY Erica Balch

September 11, 2020

On April 11, 1955, philosopher, peace advocate and Nobel laureate Bertrand Russell – one of the greatest intellectuals of the 20th century – received a letter from his longtime acquaintance, Albert Einstein, who was near death.

Weeks earlier, Russell had authored a statement warning of the dangers of atomic weapons and urging world leaders to seek peaceful solutions to international conflict. Hoping to unite the world’s greatest scientific minds behind what would later become known as the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, Russell had written to Einstein asking for his endorsement.

In a short, three-sentence reply, Einstein, a fierce opponent of nuclear proliferation wrote, “I am gladly willing to sign your excellent statement.”

Einstein died just seven days later. His letter in support of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto was his last public act.

This letter, and many others written to Russell by some of the most recognizable figures of the 20th century, are part of a special online exhibit curated by McMaster University Library librarian, Rick Stapleton.

Dear Bertie: a selection of letters to Bertrand Russell contains forty letters from McMaster University Library’s extensive Bertrand Russell Archives which help shed light on key periods in Russell’s remarkable life.

Learn more about Bertrand Russell’s life and work

The exhibit includes letters written by political leaders such as John F. Kennedy and Indian Prime Minster Jawaharlal Nehru and civil rights leader James Baldwin, as well as letters written by literary figures like Aldous Huxley, George Bernard Shaw and peace activist Vera Brittain. The collection also includes letters written by those who knew Russell best like his lover Constance Malleston and even his grandmother, Frances Russell.

“Even through the Bertrand Russell Archives and Research Centre isn’t currently open to the public, students and scholars can still explore some of its fascinating materials through these letters,” says Stapleton. “I hope the exhibit will not only provide a sense of who Bertrand Russell was and what’s in his archive, but also leave people curious to learn more.”

Below, Stapleton shares some of the letters highlighted in the exhibit and explains what makes them so significant:

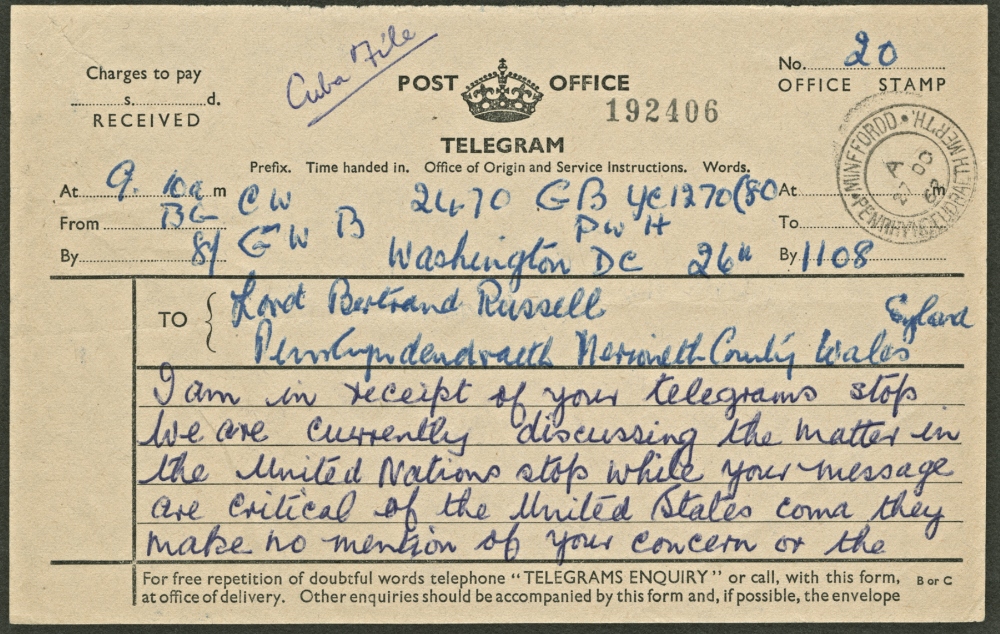

“Your attention might well be directed to the burglars rather than to those who have caught the burglars”

John F. Kennedy to Bertrand Russell, October 26, 1962

The Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 was perhaps the closest the world has come to nuclear war. On October 23, the day after the American blockade was announced, Russell dispatched telegrams to President Kennedy and Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev.

To Russell, the obvious solution was for “the United States not to invade Cuba” and for “the Soviet Union not to give armed support to Cuba.” To both leaders he pleaded for calm, but while his message to Kennedy pronounced that there was “no conceivable justification” for the blockade—which was in keeping with his earlier statement—his message to Khrushchev offered no criticism of Russia’s “armed support to Cuba.”

On October 24 Russian radio broadcast a letter from Khrushchev that was, in fact, a reply to Russell’s telegram of the previous day. Khrushchev’s reply to Russell did not acknowledge the installation of missiles in Cuba but did offer a commitment to “do everything in our power to prevent war from breaking out.”

Russell seized upon this statement and immediately issued a further telegram to Kennedy urging him to “make a conciliatory reply to Khrushchev’s vital offer.” Kennedy’s utter annoyance and disdain for Russell’s overture is evident in his reply telegram, in which he dismissively tells Russell: “your attention might well be directed to the burglars rather than to those who have caught the burglars.”

Russell was not yet finished, however, and further telegrams were sent to Kennedy, Khrushchev, Castro throughout the standoff. On October 28, the crisis ended. The resolution came about primarily because of direct communications between Kennedy and Khrushchev and not because of Russell’s involvement. Nevertheless, Russell’s role cannot be completely overlooked, at least in the popular imagination.

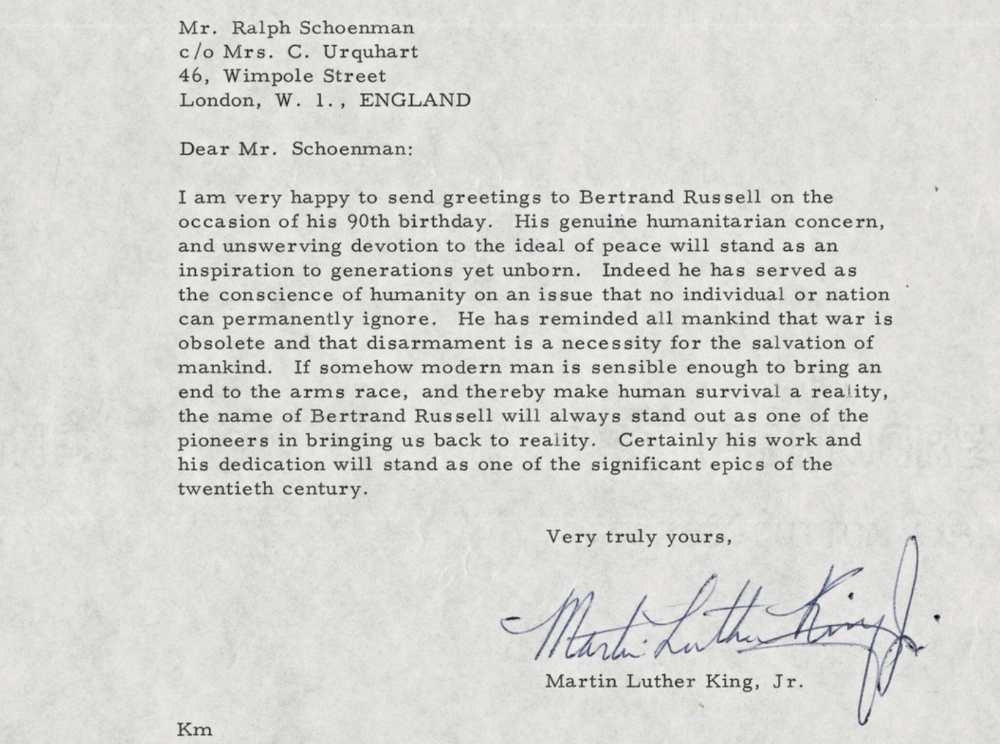

“he has served as the conscience of humanity”

Martin Luther King Jr. to Ralph Schoenman (Russell’s secretary)

In the months leading up to Russell’s 90th birthday on May 18, 1962, his secretary, Ralph Schoenman, solicited tributes from many well-known world figures including this letter from American civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr.

Russell was an admirer and supporter of King’s non-violent stance for racial equality in the United States, while King, as is obvious from this letter, was equally admiring of Russell’s stand for peace. He tells Schoenman that Russell’s “genuine humanitarian concern, and unswerving devotion to the ideal of peace will stand as an inspiration to generations yet unborn. Indeed he has served as the conscience of humanity…”.

Russell had long been sympathetic to black civil rights and, as the 1960s went on, would speak in support of such figures as Muhammad Ali, Dick Gregory, and Malcolm X. In 1965, Russell wrote in “The Negro Rising,” “The oppressed Negro nation is rising against its three hundred year subjection. Why should people not revolt against conditions wherein they are shot down or beaten to death in police cells?” Russell was largely condemned in the American media for such provocative statements.

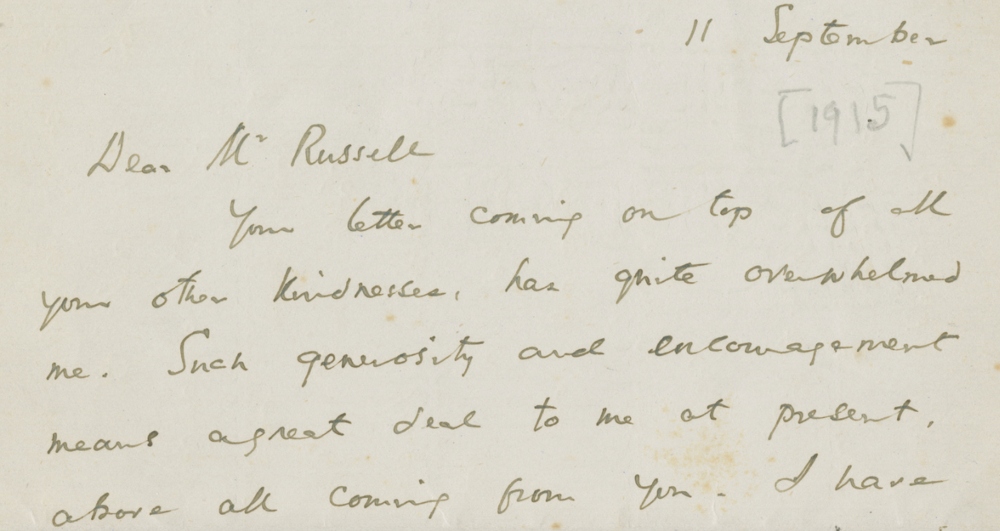

“Such generosity and encouragement mean a great deal to me at present”

T.S. Eliot to Bertrand Russell, September 11, 1915

In the spring of 1914 Russell was a visiting professor at Harvard. One of his students was T.S. Eliot (1888-1965) who was pursuing a graduate degree in philosophy. As Russell recalled in his Autobiography, “I had a post-graduate class of twelve, who used to come to tea with me once a week. One of them was T.S. Eliot, who subsequently wrote a poem about it, called ‘Mr Apollinax’.” The poem was first published in Poetry in 1916 and would appear in Eliot’s first book, Prufrock and other observations, in 1917.

Russell took on a mentoring role in Eliot’s life which he believed he sorely needed. As Russell explained to Ottoline in a July 1915 letter, while he found Eliot “exquisite,” he also believed him to be “listless.” Russell used his connections to help Eliot receive writing commissions. He also lent the Eliot and his wife Vivien a room in his London flat. It is in response to Russell’s offer of his flat that we find Eliot writing this September 1915 letter. The letter reveals the esteem and gratitude Eliot felt for Russell at this time.

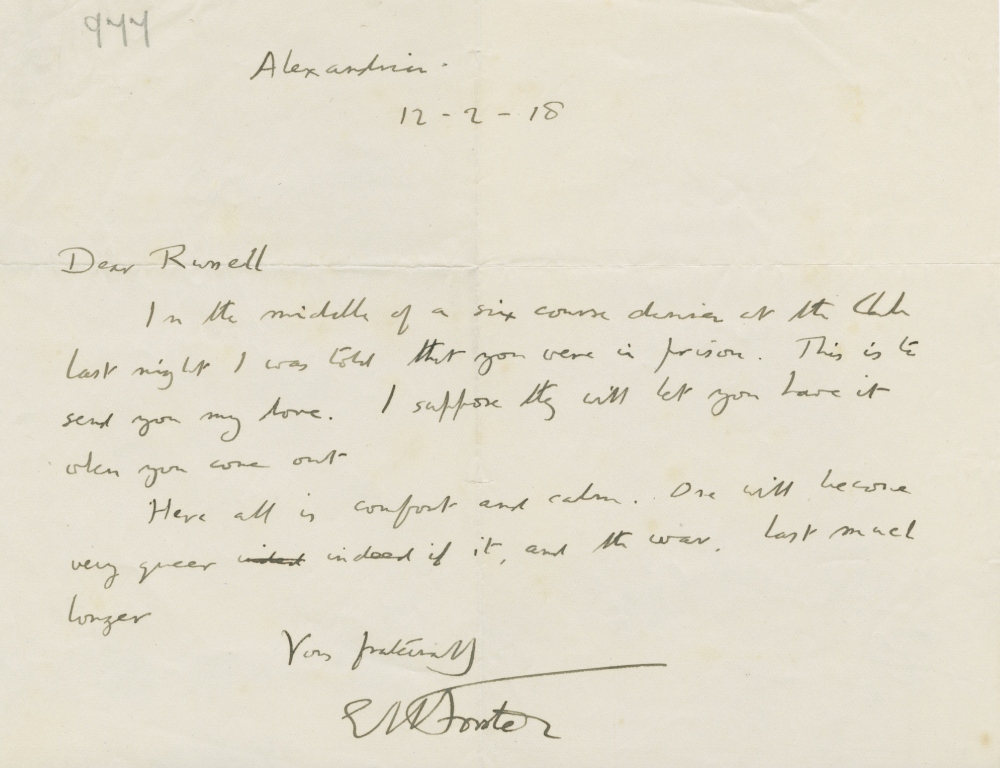

“I was told that you were in prison. This is to send you my love”

E.M. Forster to Bertrand Russell, February 12, 1918

By the time of this 1918 letter, E.M. Forster (1879-1970) was already the celebrated author of four published novels, including A Room with a View (1908) and Howards End (1910). He and Russell had become acquainted when Forster was an undergraduate at Cambridge from 1897 to 1901 while Russell held a fellowship there.

When the First World War broke out, Russell would see something of a kindred spirit in Forster and others of their mutual friends and acquaintances who opposed the war. Russell’s anti-war position caused him a great deal of personal difficulty, including a sentence to Brixton prison in 1918. It was upon hearing of Russell’s sentence that Forster was prompted to write.

There are only three other personal letters from Forster to Russell from the early 1900s in the Russell archives, and then a few exchanged between them in the 1960s. But despite this lack of documentation, they would remain friends for the rest of their lives. It was of great delight to Russell that Forster attended his 90th birthday celebration in 1962 and was one of the friends to make a speech on that occasion. Eight years later, in 1970, Russell and Forster would die within a few weeks of each other.

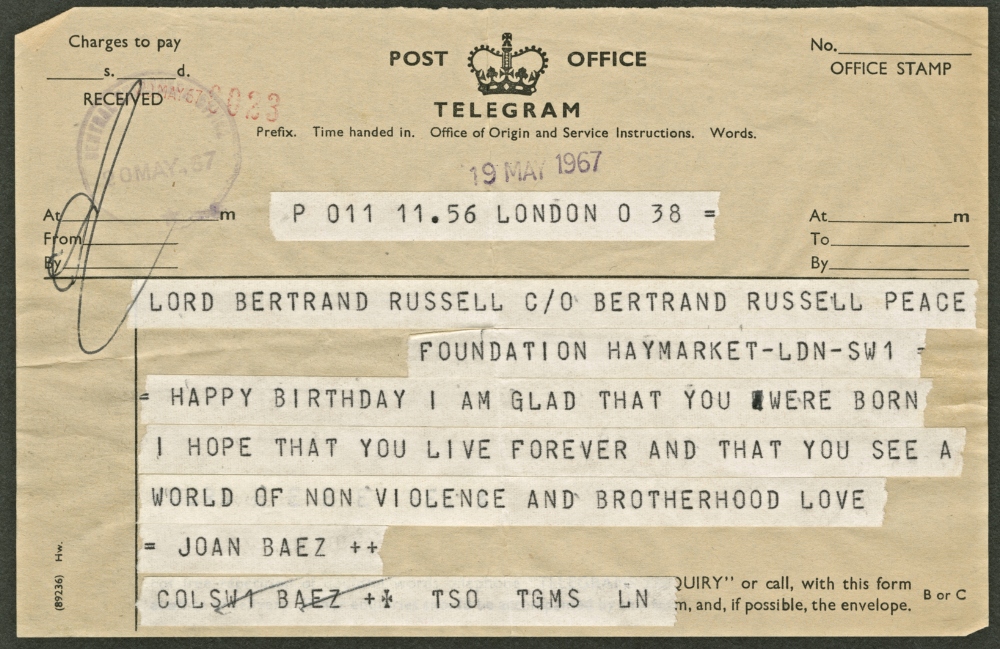

“I hope that you live forever”

Joan Baez to Bertrand Russell, May 19, 1967

American singer-songwriter and activist Joan Baez (b. 1944) was one of hundreds of people who sent good wishes to Russell on the occasion of his 95th birthday in May 1967. In the telegram displayed here, she tells Russell: “I hope that you live forever.” Along with other young musicians of the time, including Paul McCartney, John Lennon, and Yoko Ono, Baez was inspired by Russell’s stand against nuclear weapons and the Vietnam War.

There is no indication in the Russell archives that a reply to Baez’s birthday telegram was ever sent, nor is there any other correspondence between them. Russell died two-and-a-half years later, on February 2, 1970. Baez, in part inspired by Russell, continues her crusade more than fifty years later.

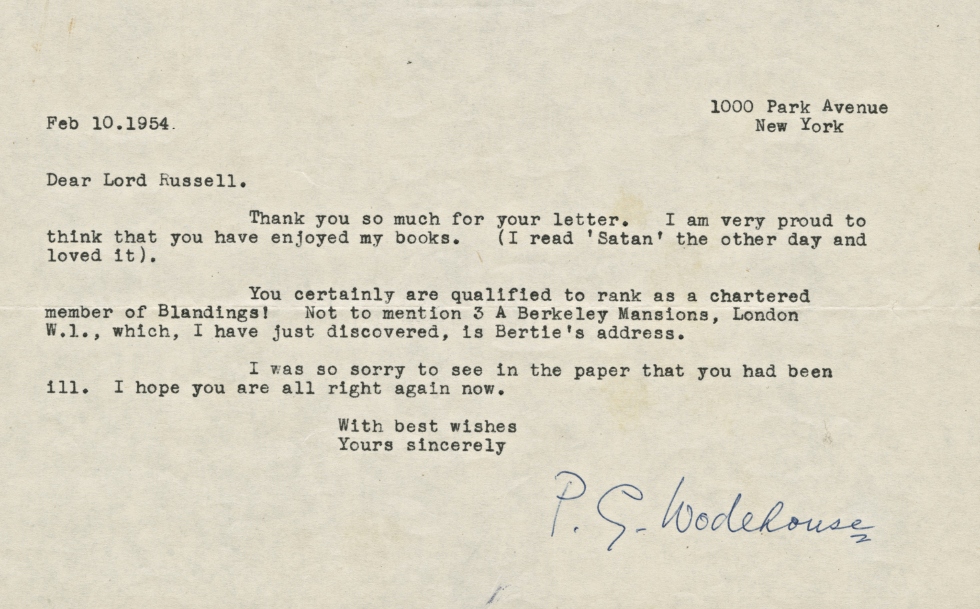

“You certainly are qualified to rank as a qualified member of Blandings!”

P.G. Wodehouse to Bertrand Russell, February 10, 1954

Unbeknownst to many who admired Russell for his great intellect and peace activism, he was a life-long reader of popular fiction. One of his favourite authors was P.G. Wodehouse.

Russell so enjoyed Wodehouse’s work that he wrote him a fan letter in 1954, telling the author: “In common with the rest of mankind, I derive great pleasure from reading your books.” Russell then went on to “far more weighty matters,” outlining his common characteristics with the fictional Bertie Wooster of the Wooster and Jeeves stories, as well as with the fictional residents of Blandings Castle: “My name is Bertie; I had an aunt called Agatha and an uncle called Algernon; I came within an ace of being called Galahad; and my great grandfather put a plaque in his garden to commemorate a victory over his head gardener.”

Wodehouse’s equally entertaining reply is featured here. He tells Russell: “I am very proud to think that you have enjoyed my books.” He then goes on to honour Russell with: “You certainly are qualified to rank as a chartered member of Blandings!” This is the only exchange of letters between them in the Russell Archives.