‘Everyone is vulnerable to propaganda’

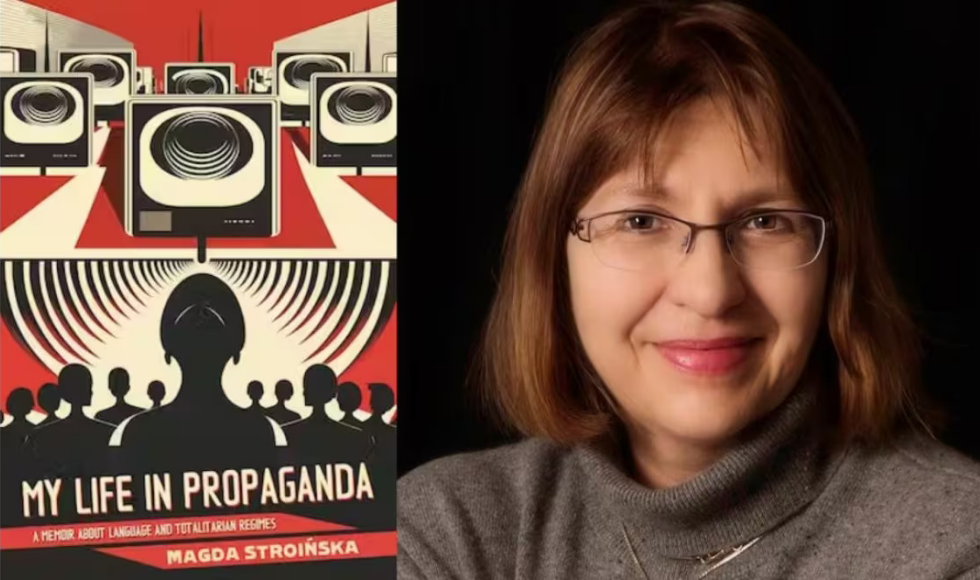

Magda Stroínska’s new book, My Life in Propaganda: A Memoir About Language and Totalitarian Regimes, is part memoir of her childhood in Communist eastern Europe, part academic exploration of how totalitarian regimes use propaganda.

BY Sara Laux, Faculty of Humanities

October 16, 2023

Magda Stroínska’s new book, My Life in Propaganda: A Memoir About Language and Totalitarian Regimes, is part memoir of her childhood in Communist eastern Europe, part academic exploration of how totalitarian regimes use propaganda.

“It seems to me that propaganda and thought manipulation have become some of the most important problems we face today: How do we know what is true and what is ‘fake news,’” Stroínska, a professor in the Linguistics and Languages department in the Faculty of Humanities, writes in the preface to the book.

“As I have been asking myself this question for most of my life, I hope that my own struggle with language and its representation or creation of reality may be of some help to others.”

Here, Stroínska shares some thoughts about the book, which features on CBC’s “46 Works of Canadian Nonfiction to Read in Fall 2023” book list.

Tell me about the genesis of your book, which is partly memoir, and partly academic.

I began this book in 2001 as an academic exploration of totalitarian propaganda – but after 9/11, I found it difficult to criticize the propaganda of those regimes when the language being used by the US and the coalition of countries fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq was so similar.

Examining propaganda through a personal lens became a way to combine my interest in propaganda with the anxiety over what was happening in the West after 9/11 – having grown up in Communist Poland, the events around 9/11 and the time that followed brought up memories that then made me suspicious of what was going on in the world, and I realized that the book needed to be more personal than I’d initially intended.

I was teaching a course in Intercultural Communication in Fall 2001, and September 11 was our first class. 9/11 really shaped how we conducted that class – we spent a lot of time examining ethnic stereotyping and language being used around “the enemy.”

One interesting use of language was the USA PATRIOT Act, which was an acronym for “Using and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism” – the use of the word “patriot” in the act made people feel like it was their patriotic duty to submit to the censorship and surveillance that the act entailed.

Did examining propaganda from a personal perspective change your relationship to it?

You know, I always thought that I was aware of propaganda, but I myself have been shaped by it. I was once interviewed by a history student for a piece on Radio Free Europe, which I listened to when I was growing up – and it didn’t occur to me at the time that Radio Free Europe was also propaganda. I started to realize how I had been biased as well.

Both sides used propaganda – and you start to realize that just because one side is lying doesn’t mean the other side is telling the truth.

No one is immune – everyone is vulnerable to propaganda.

What do you see as the impact of the book?

From a personal perspective, I wrote the book to be light enough for a younger generation – children of parents from eastern Europe, especially – to read and then understand their parents’ generation.

For example, many Polish families who moved to North America wouldn’t allow their children to go out for Halloween, because there was so much trauma in the country’s history that a holiday that made light of death and dead bodies seemed unthinkable. In Poland, every time you dig the foundation for a building you dig up bones from the war.

I hope the book helps shed some light on those experiences and how they shaped the older generations.

At one point, I might have thought the book would only have value to those interested in history, but now – we’ve never been under so much influence from propaganda as we are now, especially on social media, where people tend not to put in the effort to check facts.

Across the world, especially in eastern Europe, we are seeing countries who are historically used to being manipulated by propaganda fall victim to the promises made by those in the growing populist movements – which is, of course, just another kind of propaganda.

I end my courses with a slide that reads, “Question everything.” It’s up to us to be aware, to be critical, and to make the effort to find out what’s true. We need to remember that everything is biased, and we always need to have that filter on our perception.

We’re vulnerable to confirmation bias, where we tend to pay attention to what we already believe. We have to remember, though, that people are trying to manipulate us.

I purposely wrote the book for a non-academic reader, as I believe propaganda and thought manipulation are things many people are blissfully unaware of.

I’m an eternal optimist. I believe that we have enough brains to withstand this kind of manipulation – but I was given pause by a recent student in my intercultural communications class who wrote that she no longer knew what was true.

Join Magda Stroínska and learn more about her memoir at her upcoming book launch on Oct. 17 from 5-7 p.m. in TSH 201.