Five years later: The COVID-19 labour shock and its aftermath

The pandemic disrupted workplaces and labour relations and ultimately triggered a wave of strike action that is still gaining speed, Labour expert Stephanie Ross says.

BY Christopher Pickles, Faculty of Social Sciences

March 10, 2025

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted Canadian labour markets on a scale not seen since the Second World War. As businesses were forced to close and we got to grips with new remote-working technology, the relations between employers and workers were irrevocably changed.

Five years after the start of the pandemic, Stephanie Ross, associate professor in the School of Labour Studies, explains how Covid altered labour relations and caused a wave of strike action across Canada.

How big was the impact of Covid on the labour market?

The impact on the workplace and on labour relations has been huge. It was like a meteor that came from outer space that really shook up the normal course of labour relations we had become used to.

Since the late 1990s and early 2000s, the private sector saw a shift away from unionized sectors, like the manufacturing sector, toward sectors like the service industry. These sectors not only had a lower union presence, but also a big supply of available workers. Power over people’s jobs and working conditions became more concentrated in the hands of employers.

At the same time, we became used to governments, especially in Canada, intervening to restrict labour rights for public sector workers.

They put limits on how much workers could increase their wages and how much they could use their right to strike.

This manifested itself in back-to-work legislation and wage restraint legislation such as Bill 124 in Ontario, which capped public sector wage increases to 1 per cent per year for a period of three years.

So we became used to workers, whether unionized or not, having reduced leverage in their employment relationship. The pandemic really blew up that the status quo.

How did lockdown alter the labour landscape?

In the first phase of the pandemic, before we had vaccines, we had massive and sudden unemployment for lots of people as non-essential industries basically shut down.

That exacerbated what was already a difficult situation for labour, as you had lots of unemployed people and far fewer industries that would, or could, hire.

Thousands of workers were suddenly out of a job, and employers had the upper hand and could dictate the terms of employment, often to the detriment of employees.

In the fall of 2020, I researched this with Mohammad Ferdosi, Peter Graefe and Wayne Lewchuk, all from McMaster. A quarter of the 833 respondents we surveyed in Ontario reported some sort of negative change to their working conditions or interactions with their employer during the pandemic. That’s a significant minority and demonstrates the unequal power balance during that early period.

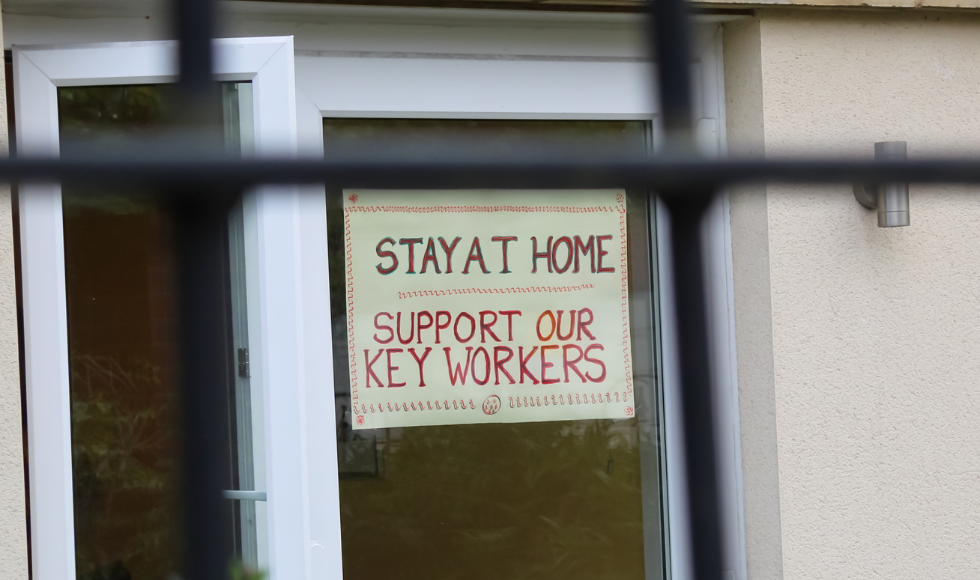

Employers were also able to leverage the public discourse around sacrificing yourself for the public good. They were able to say things along the lines of “you’re lucky to still have a job” and “you need to give a lot more of yourself because we’re in a crisis and we need people to pitch in.”

Not only that, but the new ways of working, with Zoom and other technologies, meant a recalibration of the work-life balance, as remote workers could feasibly open their laptops at home and work around the clock.

Did workers get tired of this unequal relationship?

As the pandemic wore on and society started to reopen, pent-up consumer demand meant record profits for many employers, which did not really trickle down to workers.

Many workers felt they had sacrificed a lot, but were not getting their fair share of the reward for that collective sacrifice. Employees risked their health to go to workplaces, but that did not translate into wage increases or even a healthy work-life balance.

At the same time, as the economy recovered, employers needed workers and started to think about how they could draw workers back into the labour market, and on what terms.

A lot of complex things happened over the course of that year-and-a-half that changed people’s attitudes toward what kinds of jobs they wanted do and what kinds of conditions they were willing to work under. In this phase, we saw workers gaining more individual and collective power.

For instance, people who used to work in the restaurant industry, who had tough jobs with relatively low pay, saw opportunities to work in sectors that had plentiful, remote work. Many service-industry businesses struggled to find workers as the supply of potential workers dried up.

In terms of collective action, we saw more worker militancy, and the emergence of a strike wave in Canada beginning in late 2021. In 2023, the person-days not worked because of strike action reached 6.6 million, around six times higher than it was in 2019, the year before the pandemic.

That militancy was driven by a combination of wages falling behind inflation, coupled with a sense of indignation around the unequal sacrifice and unequal reward in the wake of the pandemic.

How might all of this inform labour relations in the future?

One of the most interesting things for the labour movement is that we now have a generation of workers who, having never been on strike before, are increasingly involved in labour action.

This surge in labour action is driven by growing dissatisfaction with working conditions and the fading memories of the union defeats by neoliberal governments in the 1980s, such as the miners’ strike under British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the air traffic controllers’ strike under U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

Now, because there have been some really important recent victories through strikes, it has created the idea that, yes, this tool is now available to us again.

And frankly, I think a lot of people are thinking, “What else are we going to do?” because it’s a choice between fighting or accepting a situation that is untenable. Many more people are thinking, “What else do I have to lose?”

And that means that we now have, amongst young workers entering the labour market, the most pro-union generation, even if they’re the least likely to be unionized. The conditions are ripe for more labour action, but this generation has to seize the moment.