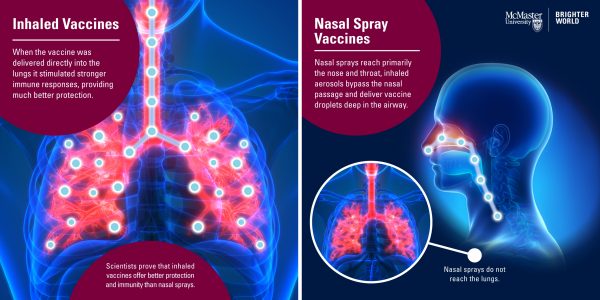

Going all the way: Scientists prove inhaled vaccines offer better protection than nasal sprays

New research comparing respiratory vaccine delivery systems in animals confirms that inhaled aerosol vaccines provide far better protection and stronger immunity than nasal sprays.

BY Michelle Donovan

June 10, 2022

Inhaled aerosol vaccines provide far better protection and stronger immunity than nasal sprays, McMaster scientists who compared respiratory vaccine-delivery systems have confirmed.

While nasal sprays reach primarily the nose and throat, inhaled aerosols bypass the nasal passage and deliver vaccine droplets deep in the airway, where they can induce a broad protective immune response, the researchers report.

For the study, published online in the journal Frontiers in Immunology, the researchers used a tuberculosis vaccine to compare delivery methods by measuring the distribution of droplets, immune responses and potency in animals.When the vaccine was delivered directly into the lungs it stimulated stronger immune responses, providing much better protection from TB.

“Infections in the upper respiratory tract tend to be non-severe. In the context of infections caused by viruses like influenza or SARS-CoV-2, it tends to be when the virus gets deep into the lung that it makes you really sick,” explains Matthew Miller, a co-author of the study who holds the Canada Research Chair in Viral Pandemics at McMaster University.

“The immune response you generate when you deliver the vaccine deep into the lung is much stronger than when you only deposit that material in the nose and throat because of the anatomy and nature of the tissue and the immune cells that are available to respond are very different,” says Miller.

“This study for the first time provides strong preclinical evidence to support the development of inhaled aerosol delivery over nasal spray for human vaccination against respiratory infections including TB, COVID-19 and influenza,” says Zhou Xing, co-investigator of the study and a professor at the McMaster Immunology Research Centre and Department of Medicine.

More than 6.3 million have people died during the COVID-19 pandemic, and respiratory infections remain a significant cause of illness and death throughout the world, driving an urgent and renewed worldwide effort to develop vaccines that can be delivered directly to the mucous lining of the respiratory tract.

Scientists at McMaster, who have developed a unique inhaled form of COVID vaccine, believe this deep-delivery method offers the best defence against the current and future pandemics.

A Phase 1 clinical trial is currently under way to evaluate the inhaled aerosol vaccine in healthy adults who had previously received two or three doses of an injected COVID mRNA vaccine.

Nasal mist flu vaccines have been shown to be highly effective in children, but much less effective in adults, leaving injectable flu vaccines as the most popular choice for seasonal flu vaccinations.

Previous research by the McMaster team has shown that in addition to being needle-free and painless, an inhaled vaccine is so efficient at targeting the lungs and upper airways that it can achieve maximum protection with a much smaller dose than injected vaccines.

The research is part of Canada’s Global Nexus for Pandemics and Biological Threats at McMaster, which brings together an international network of researchers, government, industry, health care and other partners with the goal of finding solutions to the current pandemic, while preparing for future global health threats such as antimicrobial resistance.