BY Written by Sara Laux. Photos and video by Colin Czerneda.

January 17, 2024

From McMaster to Metaponto: What decades of research has unearthed about ancient Italy

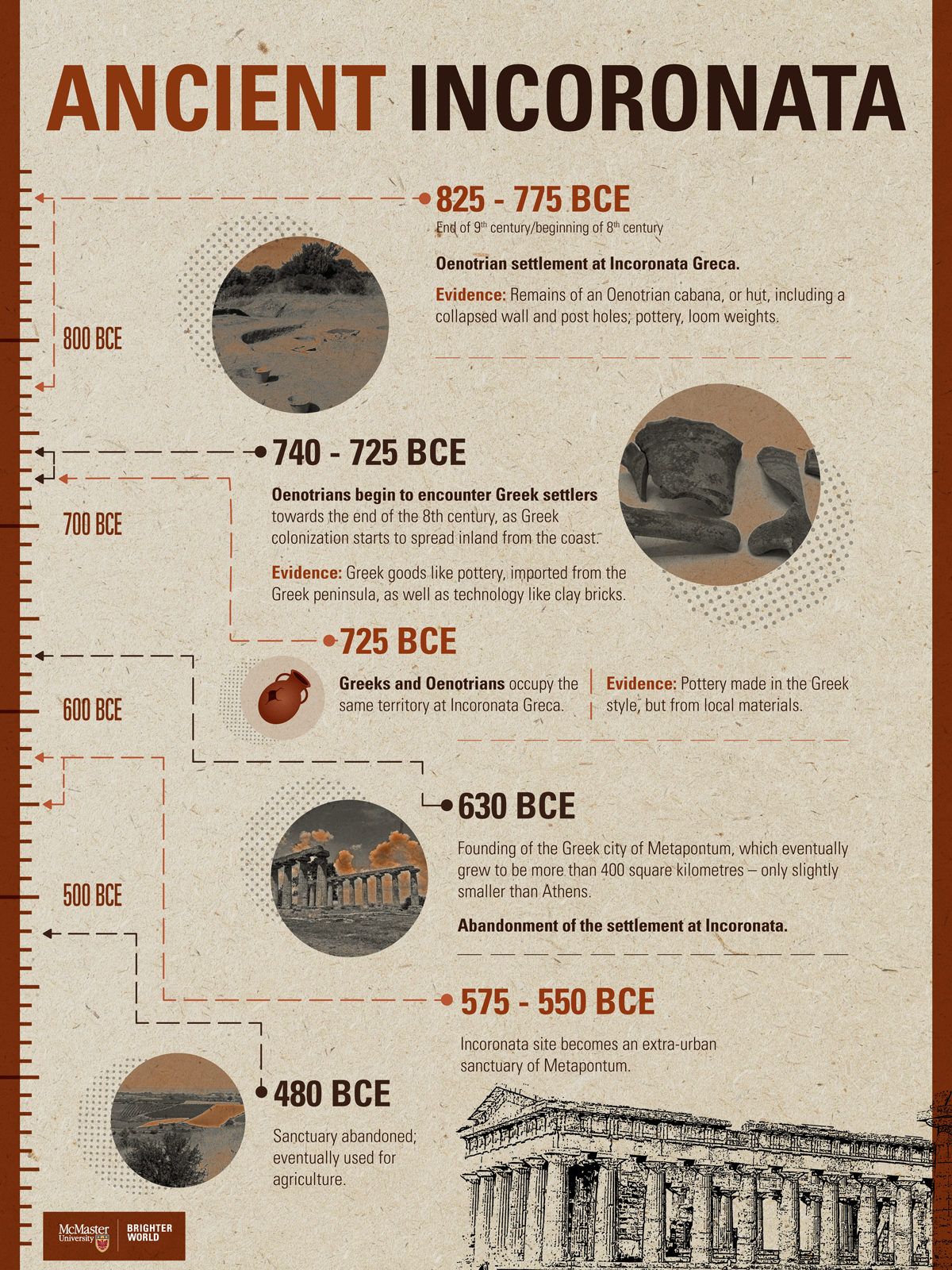

The Metaponto Archaeological Project, an ongoing collaboration between McMaster and St. Mary’s University, is uncovering the early history of interactions between the indigenous people of Italy and the Greek settlers who began to colonize the area almost 3,000 years ago.

The Incoronata Greca archaeological site commands a 360-degree view of farmers’ fields, greenhouses growing high-value fruits like apricots, kiwis and strawberries, and the water towers that serve the towns in the area.

Incoronata means “crowned” in Italian, and, high above the Basento River Valley in southern Italy, it’s easy to see where the name comes from.

It’s this spot where the Metaponto Archaeological Project, an ongoing collaboration between McMaster and St. Mary’s University in Halifax, is working to uncover the early history of interactions between the indigenous people of this area, the Oenotrians, and the Greek settlers who began to colonize the area almost 3,000 years ago.

This section of Italy, now in the administrative region of Basilicata and located on the arch of Italy’s boot, was once part of a larger area of Greek colonization that began in the 8th century BCE, encompassing the coastal areas in much of southern Italy and Sicily and which the Romans would eventually call Magna Graecia, or “Greater Greece.”

In the 9th and 8th centuries BCE, though, before Greek settlers arrived, Incoronata itself was populated by the Oenotrians, an indigenous group who lived within Basilicata, surrounded by other ancient tribes, including the Chones and the Brutii.

Judging from Greek material found at the site, like pottery and mud bricks, it seems that the Oenotrians at Incoronata encountered Greek settlers near the end of the 8th century BCE as Greek colonization continued to spread throughout the area. Evidence for Greek settlers becomes even stronger when, shortly after 725 BCE or so, artifacts start showing up made in the Greek style, but using local materials.

“Greek pottery is very fragile, and can be easily broken or lost in transit,” explains Spencer Pope, a professor of Greek and Roman studies at McMaster and co-director of the Metaponto Archeological Project. “That isn’t the case for Greek potters – so rather than try to import their fragile pottery, the potters themselves settled in Incoronata, took the local materials that were available and the Greek style they knew, and crafted goods for the people around them.”

In this area, at least, that points to a relationship not of violent conquest, but of mutually productive commercial exchange – one that continued for at least a century.

And then, around 630 BCE, it all came to a screeching halt.

No one is entirely sure why. There’s speculation that there could have been a violent confrontation or other negative interactions – but those ideas aren’t really confirmed by the evidence at the site.

However, Metapontum, a major Greek settlement just eight kilometres to the south of Incoronata, was founded around the same time. Quickly growing to more than 400 square kilometres, Metapontum, now Metaponto, was just about as big as Syracuse, then a major Greek city in Sicily, and only slightly smaller than Athens.

It’s possible that the residents of Incoronata abandoned their settlement for better opportunities in the big city. There’s also evidence that suggests that the Oenotrians had been pushed further inland by the 6th century BCE, as Greek settlement encroached further and further from the coast.

Whatever the reason for the site’s abandonment, by the second quarter of the 6th century, Incoronata had gone from being a settlement where Oenotrians and Greeks lived side by side, to being an extra-urban sanctuary of Metapontum – an area outside the city centre where Metapontines could come to worship and, Pope theorizes, potentially do business or have political meetings under the watchful eyes of the gods.

It’s also possible that the Greeks made Incoronata a sanctuary specifically because of a lingering memory of a time when the site was, in fact, a settlement.

“The site is beautiful, and it has a commanding view, and it seems very ethereal and close to the gods,” says Pope. “As the dig’s co-director, Sveva Savelli, has pointed out, it may also have been selected because of a vestigial memory of encounters with Oenotrians, who by the 6th century had been pushed further inland. It was a place where the Metapontines had interacted peacefully and productively with the indigenous populations.”

Incoronata Greca had been home for both Oenotrians and Greeks at one time. Pottery sherds and the remains of building materials make that clear. But what did that home look like?

While there are lots of literary and historical sources that describe the spread of Greek settlements throughout southern Italy, they don’t spare much ink writing about the populations who were already there.

History, after all, is written by the winners – and those who could write. And assumptions about whose history is important can persist across centuries.

“Because of the dominance of things like Greek and Roman architectural styles and the dissemination of works by Greek and Roman authors throughout Europe and into North America, it’s easy to get a view that this was the only culture from antiquity, which is completely incorrect,” says Pope.

“In fact, the Mediterranean was a vibrant territory that had many cultures closely interacting, each one learning from the next, exchanging goods, exchanging know-how, and creating a mutually productive economic trade network.”

This isn’t a new idea, and the Metaponto Archaeological Project team is just the latest in a long line of researchers who have been working to bring it to light.

The project builds on several decades of exploration, starting just after World War II, when Italian archaeologists realized that aerial photos taken by the RAF during the war showed possible evidence of human settlement in the countryside around the large Greek urban centres.

As interest in the archaeology of the countryside, or chora, grew – and the threat of contemporary agricultural and other development loomed. Piero Orlandini from the University of Milan and then Dinu Adamsteanu, the region’s first regional superintendent of antiquities, led efforts to preserve, survey and excavate evidence of rural settlement in the chora around Metapontum and elsewhere in Basilicata.

From there, archaeologist Joseph Carter, director of the Institute of Classical Archaeology at the University of Texas at Austin, led a series of excavations at Incoronata and other sites in the area in the early 1970s, continuing well into the 2010s.

Other work by the University of Milan and the University of Rennes 2 is still ongoing on other spurs of the hill.

Taking over from Carter’s work, the McMaster/Saint Mary’s team first began doing field surveys at Incoronata Greca in 2017, literally walking the fields to see what could be found on the surface and cataloguing those finds on a map. A concentration of finds can indicate a settlement – and the types of finds can provide clues to how the land was used. Domestic pottery? Probably a farm, or homestead. Tiles and fineware? Likely a tomb or necropolis, away from a residential area.

The field surveys took two years. In 2019, excavation began.

When the team returned in 2022 after the COVID-19 pandemic halted work, excavation began anew – yielding some exciting new finds.

“We started our work at Incoronata Greca with the idea of understanding the old excavations better,” explains Sveva Savelli, an associate professor of ancient studies and intercultural studies at St. Mary’s University, and the Metaponto Archeological Project’s co-director.

“Our idea was to try and find context to the data that were made available to us at the start of this work. Last year, we were lucky and started to see that some of the evidence discovered in the ’70s were not just occasional finds, but related to an important part of the indigenous settlement – so we decided to expand our research and see if we could find out more about the indigenous Oenotrian settlement.”

And each year, the team assembles more parts of the puzzle, leading to a greater understanding of all the civilizations here – not just the ones who wrote about it.

It’s dusk, and after several days of rain and unsettled weather, the weather has finally been dry enough to eat dinner al fresco on the second-floor terrace of the two-storey building where the project’s graduate students and professional collaborators stay during excavation season.

It’s a little buggy, but everyone’s glad to be outside. Even the resident feral cats have stretched out in the last of the sunset on the ground below, as the sounds of conversation and clinking cutlery drift down from above.

Not every archaeological dig has access to accommodations that have a functioning kitchen, showers and bedrooms – not to mention a terrace with a view of the sunset over the surrounding rooftops.

This building, along with another space used as a library and study hall, is on the expansive grounds of the Azienda Agricola Sperimentale Dimonstrativa at Pantanello, a large agricultural research facility and seed bank operated by Basilicata’s department of agriculture and forestry and directed by Dr. Francesco Cellini .

It’s an arrangement, along with the use of the lab in Metaponto, that’s thanks to the work of Carter and the team from the University of Texas, who completed several major excavations within walking distance, including a sanctuary, a tile-making facility, and a necropolis – in fact, ancient sarcophagi line the streets around the facility. And when McMaster and St. Mary’s took over from the University of Texas team, they continued the tradition of using the Pantanello buildings as a research centre and, just as importantly, a home away from home.

The facility at Pantanello is a perfect illustration of how much international collaboration continues to go into making something like the Metaponto Archaeological Project happen.

Pope and Savelli work under the auspices of the Superintendency of Cultural Resources of Basilicata, the local branch of the Italian Ministry of Culture.

While the Metaponto team are entrusted with excavating, cleaning, cataloguing and storing what they find, everything that’s unearthed remains the property of the Italian government – meaning that unless there’s an arrangement made to borrow artifacts for an exhibit or study, finds stay in the country and can’t be removed.

“I was seven years old when I saw Indiana Jones for the first time,” says Pope. “We may not face bad guys on a regular basis – although we do actually have snakes here – but we do strongly support the idea of preserving artifacts so they can be enjoyed by all. What we uncover here belongs to the Italian people, so maybe we need to amend Indy’s famous phrase: “It belongs in a local museum.”

There’s also regular contact with local government. Last year, the mayor of Pisticci, in whose territory the Incoronata site is located, visited the excavation, welcoming the team back after the COVID-19 hiatus.

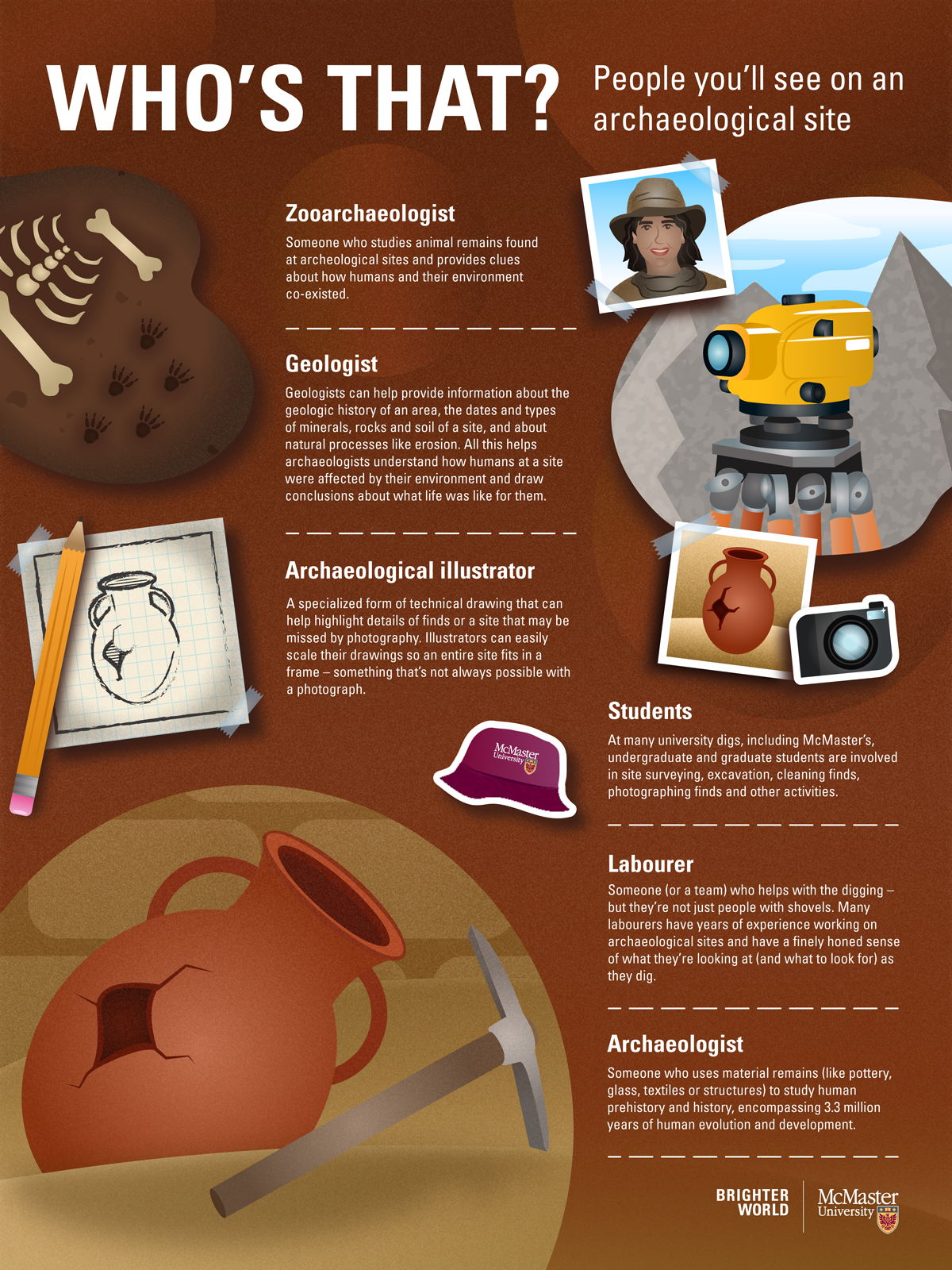

In fact, the team itself is the product of cooperation and partnership. There’s the connection between St. Mary’s and McMaster, of course, but there’s also a group of local laborers who literally help with the heavy lifting that goes along with excavation. The team also works with an international group of professional partners: archaeologists, geologists, archaeological illustrators and zooarchaeologists who, this year, have arrived from all over Europe.

“So many skills are involved in an archaeological excavation,” says Savelli. “Working in teams is standard. It’s the only way to success – a balance of different interests and educations.”

As different as the disciplines can be, they’re united in a love of material culture – and sharing what that reveals about the history of humanity.

“The initial feeling of finding something is invigorating and empowering – we’re the first ones looking at an object that has been buried for 3,000 years,” says Pope. “We’ve been entrusted with this important scientific and humanistic work, and we are so very grateful for the opportunity.”

Want to learn more about the Metaponto Archaeology Project? Click here to explore the history of the project, learn more about the student experience and discover other archaeological initiatives in Italy.