How Russians have helped fuel the rise of Germany’s far right

In this February 2016 photo, people wave German flags in Erfurt, central Germany, during a demonstration initiated by the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party. File photo by Jens Meyer/AP

BY Petra Rethmann, Director, Institute on Globalization and the Human Condition

November 2, 2018

In October 2017, a man I’ll call Mr. K. told me that he had given his vote to Germany’s far-right Alternative for Germany party (AfD).

Mr. K. is from Karaganda in Kazakhstan, and a member of Germany’s Russian-German community. In the 2017 German elections, the AfD eased into the national parliament with more than 12 per cent of the popular vote. Mr. K., who until recently had voted for Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), said that the AfD was the only party that represented the values of the Russian-German community.

In particular, he said, the fact that the CDU has embraced same-sex marriage, and that in 2015 Merkel had welcomed more than a million Syrian refugees, had been a mistake.

Mr. K. is not alone. Since 2015, the AfD has been actively courting Germany’s Russian community, even setting up a network within the party to specifically address their concerns. The strategy has borne fruit, especially in the state of Baden-Württemberg, where the AfD garnered 42 per cent of the vote in Villingen-Schwenningen, and 52 per cent in Wertheim, both cities that are home to large populations of Russian-Germans.

In these places, there’s a general sense that “our” opinion has always been “swept under the rug.” “The politics of the CDU no longer resonates with us,” Mr. K. explained. “The AfD gives these people a new political home.”

The political power of Germany’s Russian community is significant. Although there are no official statistics, according to a microcensus conducted in 2014, approximately 1.5 million Russian repatriates — ethnic Germans who had lived in the Soviet Union for generations — live in Germany.

Faced discrimination

During and in the wake of the Second World War, these repatriates were heavily discriminated against in the Soviet Union, mainly because they were German.

Called “traitors” and “fascists,” they were treated as if they were enemies of the Soviet people.

After diplomatic negotiations between Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl in the late 1980s, these families migrated to Germany. Until recently, they were perceived as a group that had integrated well, although language issues and the lack of professional skills also made integration difficult.

On Jan. 24, 2016, Russian state Channel 1 reported a story later proven to be false: That a 13-year-old Russian-German girl named Lisa had been yanked off the street in Berlin and taken to a rundown apartment by three Arab-looking men who beat and raped her.

Although it was quickly revealed that the girl had lied, senior Russian diplomats continued to accuse German authorities of staging a cover-up. Referring to the alleged rape victim as “our Lisa,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov told reporters in Moscow that in Germany such cases are “swept under the carpet,” because the country wants to appear “politically correct.”

Although it’s important to note that not all Russian-Germans support the AfD, fake news and statements of support from Moscow have galvanized significant parts of Germany’s Russian community against Merkel, who’s announced she’s stepping down in January.

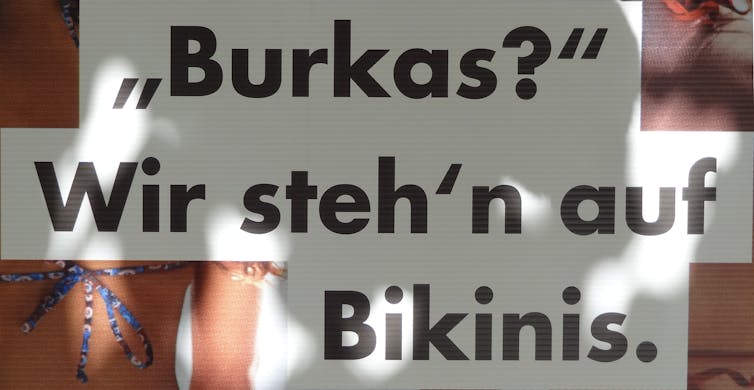

In the wake of Lisa’s story, the AfD staged dozens of protests across the country, including one massive demonstration outside of Merkel’s office in Berlin.

From their perspective, at stake was not only the “false tolerance” that, according to anti-immigrant activists, drives German politics, but also understandings and experiences of Germany history.

Russian influence in Germany

Most significantly, Germany’s acknowledgement of its responsibility for the Holocaust and Second World War is more than problematic for a number of Russian-Germans. And many Russian-Germans see themselves as victims of the war, not as the guilty party.

Russia enjoys a considerable media presence in Germany. Major Russian social media networks like Odnoklassniki (Classmates) and Vkontakte (In Contact) are popular, and satellite TV provides easy access to Russia’s television Channel 1, which is also considered Putin’s “state channel.”

Although German TV channels recognize the presence of a number of linguistic communities in the country, they almost entirely ignore Russophones. There are no Russian moderators or lead actors in serials, and members of the Russian-German community rarely participate in talk shows, where the presence of Turkish-speaking participants is common.

Germany’s Russian community is not the only friend Putin has in the country. In the recent past, leading AfD party officials, including Alexander Gauland, have met with Kremlin-loyal nationalists and Russian Orthodox Church leaders, and accepted invitations to the Yalta International Economic Forum.

The AfD welcomes the Kremlin’s anti-liberal, anti-European and homophobic ideas. While there exists no hard proof that the AfD receives financial support from Moscow, the party has received generous in-kind donations in the form of thousands of election signs and millions of copies of a free campaign newspaper promoting the AfD’s anti-refugee platforms.

Patrons are eager to stay anonymous, but AfD treasurer Klaus Fohrmann has never denied the fact that Russian money has helped the party.

Building the far right

Russia’s politics are still expansionist but it now relies not just on military might but also communications and digital strategies.

What’s more, Russia’s nativist stance against immigration, its national patriotism and its endorsement of Russian Orthodox values also appeal to far-right movements other than the AfD, including Marine Le Pen’s Front National, Austria’s Freedom Party, and Bulgarian President Rumen Radev.

In appealing to xenophobic ideas, it seeks to promote destabilization within a given political entity and country.

This is a Russian political strategy of hollowing democracy from the inside out. As Russia wins support from Europe’s right-wing movements, both European populism and Russia will grow ever stronger.![]()

Petra Rethmann is a professor of anthropology and the director of the Institute on Globalization and the Human Condition at McMaster. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.