Human case of H5N8 bird flu underscores the need for a universal influenza vaccine

Infectious disease expert Matthew Miller is working with scientists in Canada and the U.S. to develop a universal vaccine that would offer protection against influenza viruses and is designed to be effective when the virus mutates.

BY Michelle Donovan

February 26, 2021

Revelations this week that the H5N8 strain of avian flu has been detected in humans working at a poultry plant highlight the urgent need to develop a universal influenza vaccine, says a leading infectious disease researcher at McMaster University who is working toward that goal.

“We need to stay on high alert and conduct a great deal of surveillance to detect viruses that could lead to another pandemic,” says Matthew Miller, an associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences and principal researcher at the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research.

“This case underscores the importance of developing a universal influenza virus vaccine that could provide people with protection against influenza viruses that have the potential to develop into an epidemic or pandemic.”

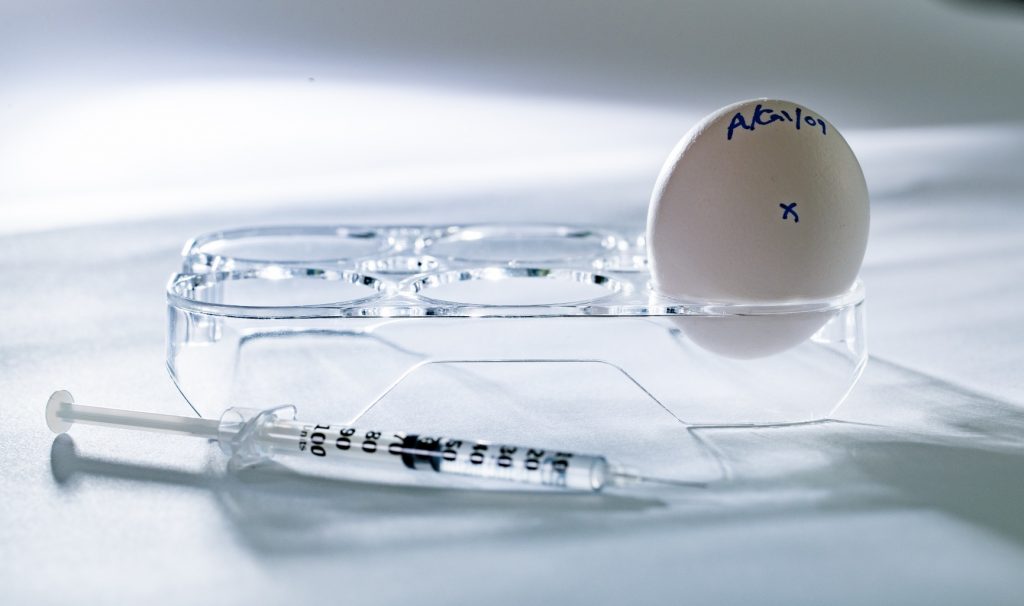

Miller’s team, which is part of Canada’s Global Nexus for Pandemics and Biological Threats, an international network based at McMaster, is working with scientists in Canada and the U.S. to develop a universal vaccine that would offer protection against influenza viruses and is designed to be effective when the virus mutates.

A universal vaccine would take the guesswork out of planning annual vaccines, which are produced to target the individual strains experts predict will dominate each flu season and would protect against all flu strains and the occurrence of flu pandemics.

Influenza has a high mutation rate

Since 1918, influenza virus has caused five global pandemics. According to the World Health Organization, seasonal flu causes severe illness in as many as three to five million people each year with approximately 300,000 to 600,000 deaths worldwide.

“Influenza viruses have a relatively high mutation rate and can share genetic material with other strains, enabling them to evolve to infect and transmit in other animal species or humans,” Miller says.

Researchers are also developing antibody-based drugs that could provide universal protection, which could be administered to patients to provide short-term protection before a vaccine is available.

Several workers at a poultry plant in Russia were infected with the H5N8 strain in an outbreak which occurred in December. While highly pathogenic strains of avian influenza viruses have caused human outbreaks and serious illness, there were no signs of transmission between workers in this case.

Generally, these types of avian influenza viruses tend to spread directly from birds to people, but have not evolved to spread efficiently from person to person, says Miller, which likely explains why they have not yet caused pandemics.

The first known H5N8 influenza virus was detected in Ireland in the early 1980s. In 2014, more than 12 million birds were culled when it emerged in South Korea. Since then, there have been outbreaks in Europe, Asia, North American and Africa.