“I believe that the moment has come to melt down our tin plates and tin spoons and forge them into bullets”

BY Sara Laux

February 1, 2019

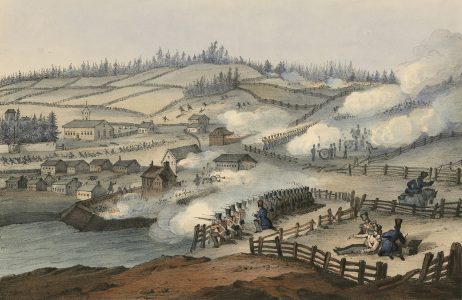

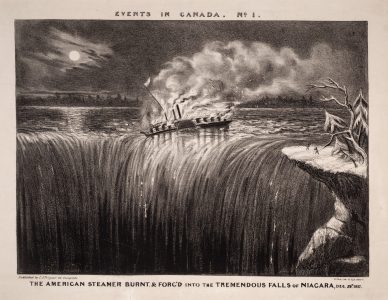

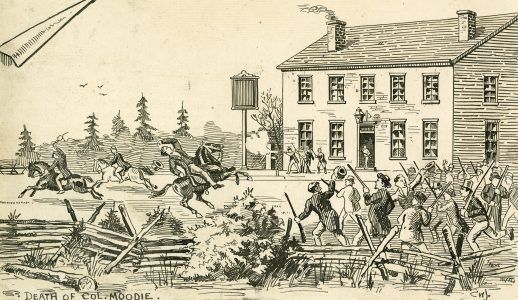

In 1837 and 1838 – 30 years or so before the Dominion of Canada “came noisily into existence” – armed uprisings took place in Lower and Upper Canada, now Quebec and Ontario.

Led by Louis-Joseph Papineau in Lower Canada and William Lyon Mackenzie in Upper Canada, the Canadian Rebellion, as it came to be known, was a reaction to the cronyism and patronage that characterized the colonial governments of the time.

And while both were short – skirmishes in late 1837 and early 1838, and another in November 1838 – they were important: They prompted the writing of the Durham Report, which recommended that the two colonies be united. This led to the creation of the Province of Canada in 1841 and, eventually, to the formation of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867.

An important piece of Canadian history, for sure — but one that’s not very interesting to historians outside Canada.

At least, that’s what Maxime Dagenais thought when he went to do a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania in 2014.

“From a military perspective, in the past historians have characterized the Canadian Rebellion as failed,” says Dagenais, who’s now the co-ordinator of McMaster’s L.R. Wilson Institute for Canadian History. “There were so many other things going on in the U.S. at that time – the market revolution, the panic of 1837, issues with slavery – that I assumed no one would be interested in my rebellion.”

He soon discovered he was wrong.

In fact, American scholars were very much interested in the Canadian Rebellion. Dagenais realized that, far from being small-scale, localized events, the rebellion as a whole had an impact felt throughout the fledgling United States, on issues from economic reform and slavery to the defeat of Martin Van Buren in the presidential election of 1840.

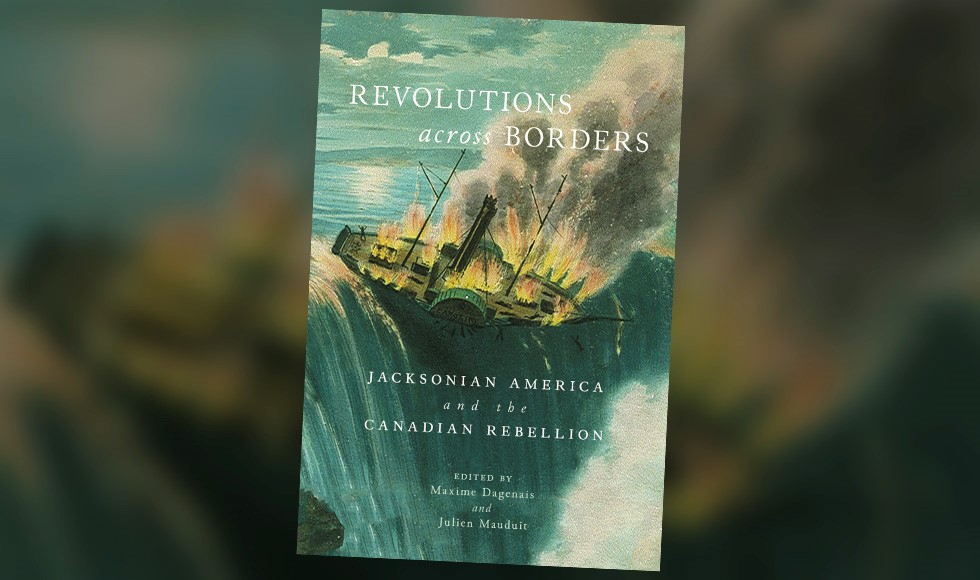

That perspective has now led to the publication of a book, Revolutions across Borders: Jacksonian America and the Canadian Rebellion. Co-edited by Dagenais and Wilson Institute assistant professor Julien Mauduit, the book examines the Canadian Rebellion from a transnational perspective – a way of looking at it that really hasn’t been done before.

“Traditionally, it’s been interpreted from a very local perspective – Ontario and Quebec, separately,” explains Mauduit. “We’re looking at it as a pan-Canadian event, but we’re going even further and crossing the U.S. border. Fifty per cent of the scholars in the book come from Canada, and the other half from the U.S. We have French Canadians, Anglo Canadians – the idea was to have a new look.”

Mac students are also going to get the chance to study the Canadian Rebellion this term, albeit in a slightly different way.

That’s because the rebellion is this year’s topic for History 2V03 – Remaking History, an annual experiential class that asks, “Why take history when you can make history?”

Aimed at history majors and non-history students alike, the class involves a lot of participation, but no heavy essays. Each year, the course focuses on a different moment in Canadian history, then divides students into groups to represent the different sides of the relevant issue. At the end of the term, students will have created an independent project to reflect their position, as well as participated in a class-wide debate.

“The pitch is that we’re going to bring the students to November 1837 and ask the question: will you take up arms to fight against British rule, or will you fight on the side of those rules,” says Mauduit. “When we lecture, students could become very passive. In this class, students are active every single week. It’s unique – I tell my students they won’t have this kind of opportunity anywhere else.”