Indigenous communities should be able to choose online voting, especially during COVID-19: Report

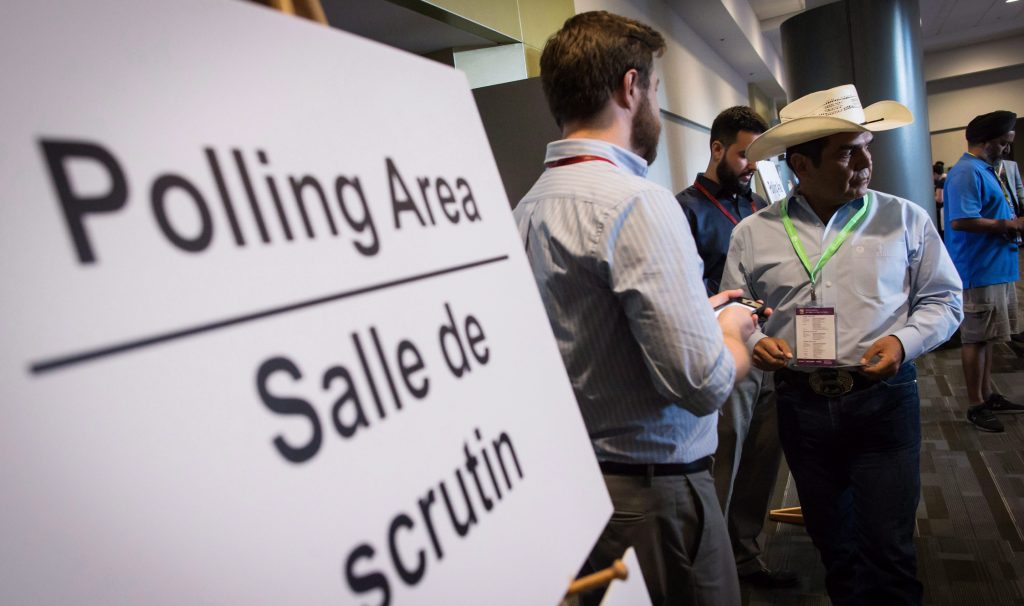

A voter waits to enter a polling area to cast his ballot for Assembly of First Nations National Chief on July 25, 2018. (The Canadian Press/Darryl Dyck)

BY Chelsea Gabel (McMaster University) and Nicole Goodman (Brock University)

May 4, 2021

Indigenous communities should be able to vote using the voting methods they choose, especially during a pandemic. Online voting is a method many Indigenous communities have deployed in recent years and others are looking to use.

While most governments have been able to make their own decisions around postponing their elections and how to conduct them during COVID-19, First Nations have felt the effects of colonial voting regulations that limit their autonomy over their own voting processes.

The Indian Act and First Nations Election Act create governments with elected chiefs and councils and place strict rules on most aspects of First Nations governance, including fixed election terms and the types of ballots that can be used. Neither piece of legislation includes a provision to extend elections or votes in crisis situations.

At the beginning of the pandemic, First Nations whose elections fall under the Indian Act or First Nations Elections Act, were forced to proceed with planned elections despite public health risks. Iskatewizaagegan (Shoal Lake) First Nation was one such community. At that same time, other elections in Canada were being postponed (like New Brunswick’s municipal elections).

The public health risks of running an election during a pandemic are magnified for First Nations. Many communities are rural or remote and may have limited access to hospitals, but are miles away from urban centres. In the past, the government’s response to outbreaks have left communities feeling stigmatized and less valued. During the H1N1 outbreak in 2009, Health Canada sent more than two dozen body bags to a Manitoba First Nation instead of other needed supplies such as masks, respirators and hand sanitizer.

Our report, Indigenous Experiences with Online Voting, provides eight best practices for communities wanting to use online voting as the COVID-19 pandemic lingers. The report also puts forth eight recommendations, which are the result of longstanding research collaborations with Indigenous communities as part of the First Nations Digital Democracy Project.

Online voting and governance of First Nations elections

Online voting has been used by First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities across Canada since 2011. In the context of First Nations, this has mostly been for the passage of ratification and agreement votes. Nipissing First Nation was the first in Ontario to pass their own constitution (Chi-Naaknigewin) and used online voting to do so.

First Nations have also used online voting for chief and council elections. To be able to use non-paper based voting methods for elections or referendums, however, First Nations must have their own election code or self-government agreement because federally derived frameworks do not allow for the use of alternative or digital voting methods.

Our top recommendation in the report is that the federal government amend the necessary regulations of the Indian Act and First Nations Elections Act to allow First Nations to choose and use their own voting methods.

This change would not only support elections and voting in pandemic and post-pandemic times, it would also support First Nations in circumstances where participation thresholds are required for the passage of votes, improve voting accessibility on and off-reserve, enhance vote tabulation efficiency, and allow for the modernization of political institutions and processes.

How online voting can help in times of crisis

Online voting is seen as a means to better connect citizens. This includes individuals living off-reserve who may not be able to make the trip home to cast a ballot, and for people living in the community who may want to vote online because of accessibility or convenience. Online voting has enhanced inclusiveness and representation while helping meet required participation thresholds for some votes.

The work conducted for the report also points to ways in which online voting and other remote ballot types could serve Indigenous communities in times of crisis. These include: maintaining relationships, enhancing community voice and supporting a willingness to innovate.

Maintaining relationships is a key factor for community health and well-being. The deployment of online voting in Whitefish River First Nation empowered the community to pass their own Matrimonial Real Property law. This sparked community dialogue regarding the law and technological adoption, particularly between elders and youth. Elections and voting are one way of nurturing these relations. Even when participation may not be possible in person, maintaining these connections is critical.

Improving participation and enhancing community voice was articulated as being important by communities. Use of online voting can facilitate remote participation and promote inclusiveness without public health risks.

First Nations are not afraid to innovate when faced with challenges. Some communities that were unable to meet required quorums with traditional paper voting were willing to try online or telephone voting to engage more citizens to ensure they could adopt their own legislation.

Enough with the excuses

First Nations across Canada are urging Indigenous Services Canada to be responsive. Our report advances recommendations to support online voting use and development. Some of these are items that the Government of Canada can take immediate action on. As noted above, this includes amending the applicable election and referendum regulations to allow First Nations to use remote voting methods.

A second recommendation for the federal government is to increase earmarked core funding that could be used to support remote voting such as online or mail-in ballots. Communities suggested that this funding should be discretionary, have the ability to be carried over, contain no claw-back option and not require reporting. The funding could also support prioritizing digital literacy, which could further reduce the impact of COVID-19 related challenges.

These proposed changes must be made with First Nations. Acting quickly with a single amendment would provide First Nations the option to continue elections as our country emerges from a third, and potentially not final wave. It would also provide space for much needed conversations about how to move forward with changes to elections.![]()

Chelsea Gabel, Associate professor, Indigenous Studies Program, McMaster University and Nicole Goodman, Associate professor, Political Science, Brock University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.