Students from McMaster and federal women’s prison to explore Indigenous Studies together

A McMaster Indigenous Studies course that will take place inside the Grand Valley Institution for Women, a federal women’s prison in Kitchener, ON, marks the official launch of a project intended to increase access to post-secondary education for incarcerated Indigenous peoples.

BY Maureen Lawlor

November 1, 2022

A new McMaster Indigenous Studies course taking place in a prison is part of a wider effort to challenge colonial stereotypes by centreing Indigenous teachings on governance, law, philosophy, art and science.

Sara Howdle will tell you that while the deep, complex and harmful relationship between the justice system and Indigenous peoples may make a prison a counterintuitive setting for this learning, it is the opposite. Instructors and students can create a space to explore diverse Indigenous perspectives and foster a learning environment that has the power to produce rich and important results.

Howdle, the assistant director of the McMaster Indigenous Research Insititute (MIRI), along with Savage Bear, MIRI’s director, are launching the course as part of the Prison Education Project, which will work to increase access to post-secondary education for incarcerated Indigenous peoples.

“There are currently a great number of critical thinkers within prison populations who have never had the opportunity to pursue higher education. MIRI is creating space at McMaster for those students because their presence enriches our university community,” says Howdle.

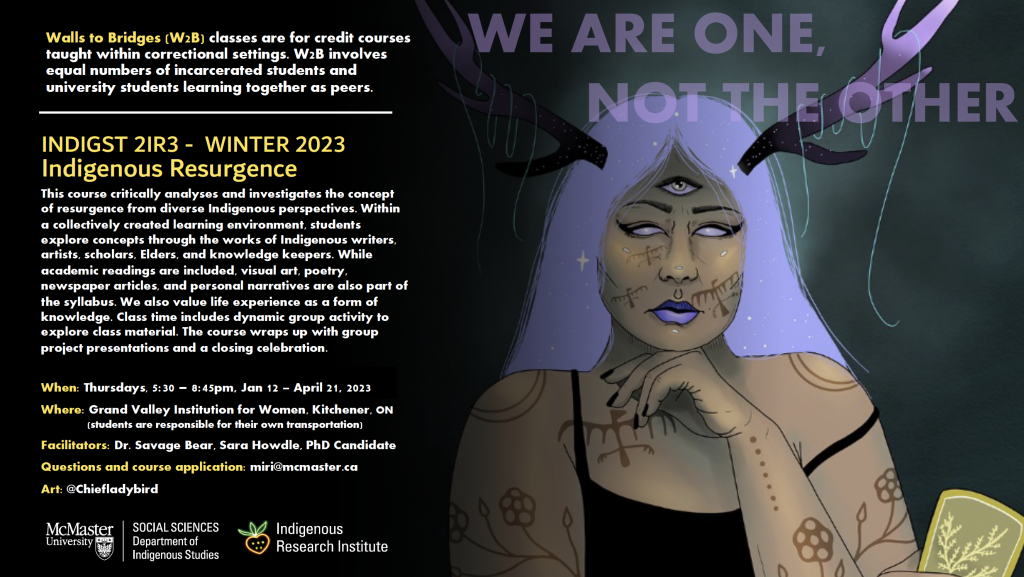

The 12 week-long course, titled Indigenous Resurgence, will take place inside the Grand Valley Institute for Women (a women’s prison in Kitchener) this January.

It will mark the official start, and the first phase, of the Prison Education Project at McMaster. The first phase sees university courses brought into prison settings where equal numbers of incarcerated and university students take courses as peers and earn the same university credit. The tuition of the incarcerated students is sponsored by McMaster.

The second phase of the project will support students in gaining university credits while they live in transition homes (sometimes known as halfway houses) after they leave carceral institutions. The third and final phase is a mentorship program for formerly incarcerated people interested in applying for university as full- or part-time students.

A dynamic and collaborative learning environment

The project is a replica of a model of a prison to post-secondary pathway for Indigenous peoples Howdle and Bear successfully established while working in the Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta, working with the Edmonton Institution for Women and the Buffalo Sage Wellness House.

The upcoming course, like the ones Bear and Howdle established at the Edmonton Institute for Women, will use the framework of the Walls to Bridges Program.

Walls to Bridges is an innovative educational program in which university or college-based classes are taught in jails, prisons and community correctional settings. Bear and Howdle both underwent the program’s instructor training and now serve on its Executive Leadership Committee.

“Walls to Bridges is often a more dynamic and collaborative learning environment than the traditional university class. We do a lot of circle work, discussing readings, arts, and film. There are small group activities to get everybody comfortable in participating,” says Howdle. “There’s no real space in Walls to Bridges for wallflowers. To just show up and take your notes, it’s just not possible for this classroom model.”

The courses culminates in a final group project that Howdle says many students have described as a transformational experience. Past classes have produced a range of projects from the forming of a collective, to beading, to singing and the creation of dioramas. Students have to navigate the limitations of the carceral setting they are in, and adapt to the restrictions their incarcerated peers have to operate under.

Untapped potential

Teaching W2B classes has been some of the most powerful and engaged teaching moments Bear says she has ever experienced.

Not only is the Prison Education Project motivated by the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples inside prisons, but MIRI wants to provide educational opportunities to incarcerated people who have been consistently marginalized and forgotten.

Bear recalls, “I remember speaking to one of our inside Indigenous students about our Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and she said, ‘You know what? We may not have been murdered or gone missing, but I think we are the forgotten ones.’ I didn’t know what to say, I had to agree.”

Bear states, “So, I see this as our job to make sure incarcerated Indigenous peoples aren’t forgotten, to open up spaces in education so everyone can benefit from their untapped potential.”

Changing the conversation

The overall project has two main benefits, says Howdle. It addresses the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the prison system, while also providing all students with the critical thinking skills to make positive changes in their own communities.

“We’re trying to address that overincarceration by offering opportunities for folks to learn about colonialism, systemic racism and critical Indigenous Studies from a non-deficit framework,” says Howdle.

“Colonial institutions have narratives about Indigenous peoples that uphold settler dominance. Stereotypes of inherent criminality and deficiency continue to justify Canadian sovereignty over Indigenous self-determination. And this arguably perpetuates systemic racism when it comes to sentencing and parole of Indigenous peoples,” says Howdle.

The Indigenous resurgence course draws on a concept established by Indigenous academics, knowledge holders and elders that centres Indigenous histories told from within the community as powerful tools for self-determination and sovereignty. In the classroom, that entails a focus on Indigenous worldviews, histories, governance systems and languages, rather than colonial policies or violence.

“Indigenous playwriters, filmmakers, authors, artists, philosophers, scientists and comedians have given us so many materials to learn about Indigenous nations and experiences as complex and diverse people,” says Howdle.

“We’re really concerned about what this means for Indigenous communities to have access to critical Indigenous studies, when previously, they may have only encountered colonial narratives imposed by settler narratives,” says the researcher. “We’d argue that more systemic change would happen in our communities when all people can learn from Indigenous knowledges.”

More voices at the table

Howdle says the MIRI team, which also includes Elya Porter and Katelyn Knott, is looking forward to putting tiers two and three of the project into action and that she and Bear are working to build connections with local carceral institutions in the hopes of providing more pathways to post-secondary education for Indigenous peoples in our community.

“This is sort of a wider issue of university infrastructural reform and providing more space for folks at universities,” says Howdle of the project.

“This work isn’t motivated by a sentiment of charity or altruism. There are incredible critical thinkers in there, and our university definitely benefits from their participation and lived experience. So, it’s part of bettering Mac’s community by making sure more voices are at decision making tables. And that starts with students.”

Registration for the INDIGST 2IR3 course is limited and students must submit an application by November 15, 2022. Students are responsible for their own transportation to and from the Grand Valley Institution for Women (GVI).

While GVI is a women’s prison, the course is open to students of all genders. Indigenous student participation is prioritized but all are welcome. Questions? Email Sara Howdle at howdle@mcmaster.ca.