McMaster researchers discover new class of antibiotics

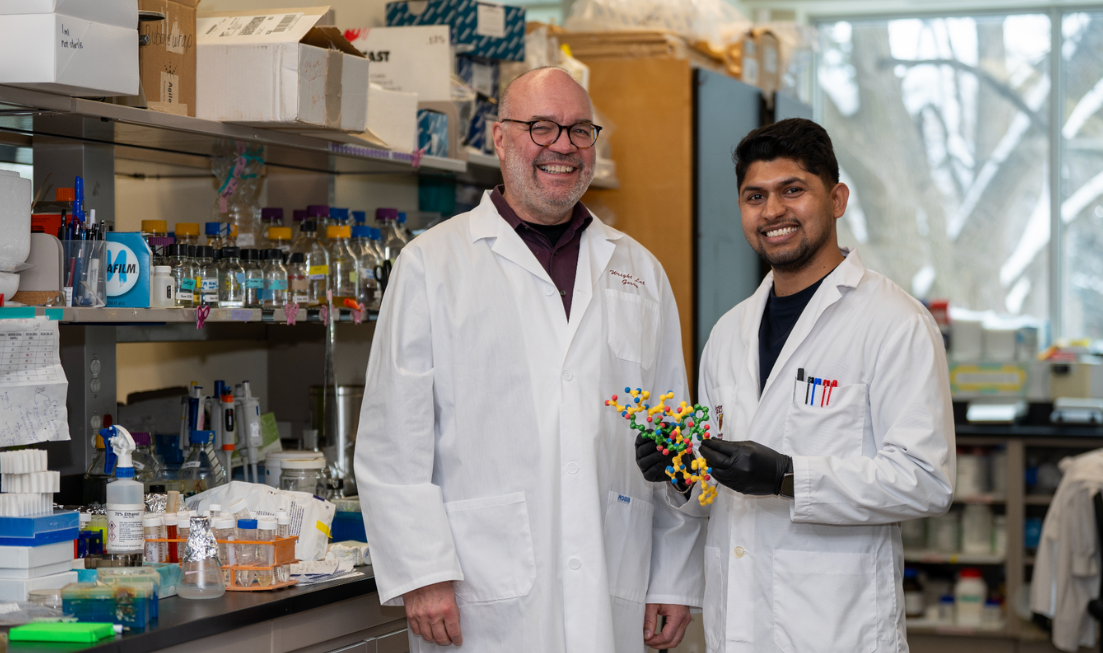

Researcher Gerry Wright, left, and postdoctoral fellow Manoj Jangra, holding a 3D-printed model of lariocidin, the new antibiotic that they discovered together. (Photo by Georgia Kirkos, McMaster University)

BY Blake Dillon

March 26, 2025

Nearly three decades after the last time a new class of antibiotics reached the market, McMaster researchers have made a breakthrough discovery that could hold the key to addressing antimicrobial resistance.

A team led by researcher Gerry Wright has identified a strong candidate to challenge some of the most drug-resistant bacteria on the planet: a new class of antibiotics called lariocidin. The findings were published in the journal Nature on March 26.

The discovery could address a critical need for new antimicrobial medicines, as bacteria and other microorganisms evolve new ways to withstand existing drugs. AMR is one of the top global public health threats, and Wright says discovering new drugs is a key part of the solution.

“Our old drugs are becoming less and less effective as bacteria become more and more resistant to them,” explains Wright, a professor in McMaster’s department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences and a researcher at the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research.

“About 4.5 million people die every year due to antibiotic-resistant infections, and it’s only getting worse.”

The new molecule, a lasso peptide, binds directly to a bacterium’s protein synthesis machinery in a completely new way from other antibiotics, inhibiting its ability to grow and survive, Wright and his team found.

“This is a new molecule with a new mode of action,” Wright says. “It’s a big leap forward for us.”

Lariocidin is produced by a type of bacteria that the researchers retrieved from a soil sample collected from a Hamilton backyard.

The research team allowed the soil bacteria to grow in the lab for approximately a year, which helped reveal even slow-growing species that could have otherwise been missed.

One of these bacteria, Paenibacillus, was producing a new substance that had strong activity against other bacteria, including those typically resistant to antibiotics.

“When we figured out how this new molecule kills other bacteria, it was a breakthrough moment,” says Manoj Jangra, a postdoctoral fellow in Wright’s lab.

In addition to its unique mode of action and its activity against otherwise drug-resistant bacteria, lariocidin checks a lot of the right boxes: It’s not toxic to human cells; it’s not susceptible to existing mechanisms of antibiotic resistance; and it also works well in an animal model of infection.

Wright and his team are now focused on finding ways to modify the molecule and produce it in quantities large enough to allow for clinical development.

Because this new molecule is produced by bacteria — and “bacteria aren’t interested in making new drugs for us” — it will take more time and resources before lariocidin is ready for market, Wright says.

“The initial discovery — the big A-ha! moment — was astounding for us, but now the real hard work begins,” Wright says.

“We’re now working on ripping this molecule apart and putting it back together again to make it a better drug candidate.”