On the 50th anniversary of the War Measures Act, we don’t need a coronavirus sequel

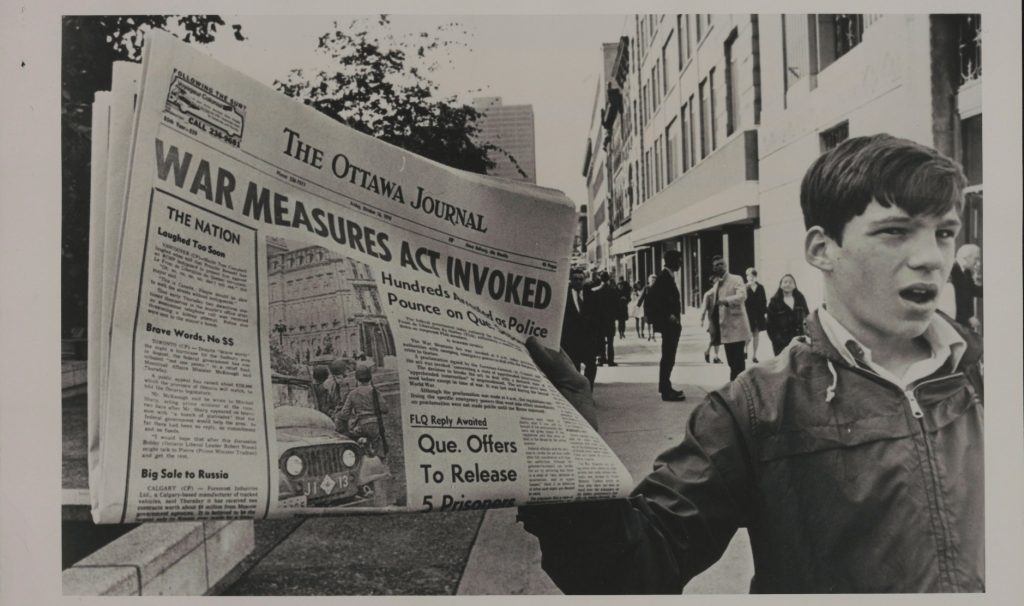

When then prime minister Pierre Trudeau brought in the War Measures Act in 1970, it was the first time the controversial law had been invoked during peace time. (Photo from the Canadian Press)

BY Maxime Dagenais and Ian McKay

May 4, 2020

Maxime Dagenais is the coordinator of the Wilson Institute for Canadian History and an adjunct assistant professor of history at McMaster University. Ian McKay is the Director of the Wilson Institute for Canadian History at McMaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ordinary citizens under siege. An atmosphere of ambient anxiety. A cloud of rumours and conspiracy theories. A Trudeau government at the helm. Sound vaguely familiar?

Welcome to Québec in 1970 — on the eve of the October Crisis. Fifty years ago in Québec might seem to be another world, yet it’s also part of our present coronavirus pandemic world.

Canada’s War Measures Act came into effect just after the start of the First World War. It gave the federal cabinet sweeping powers to censor publications, jail citizens, take over and dispose of private property. Individual lives were negatively affected. More than 8,000 men, women and children — many from the Austro-Hungarian, German and Ottoman Empires — were interned.

Life behind barbed wire was, historian Kassandra Luciuk reveals, a life-threatening ordeal mainly meted out to people judged to be “enemy aliens” because they had the bad luck to be born under the rule of the wrong empire. Historian Mary Chaktsiris further reveals that across Canada, more than 80,000 men identified as enemy aliens were forced to register with authorities, report to them regularly and experienced state control over their movement.

Unions and theatre troupes targeted

Then came Section 98, added to Canada’s Criminal Code in 1919, which made it a criminal offence to belong to any association whose purpose was to bring about “governmental, industrial or economic change in Canada” through the use of advocacy of force or violence. Its terms were so broadly defined that they were applied to trade unions, discussion groups and even theatre troupes and gymnastic clubs.

But Section 98 generated more mayhem and resistance than deference, so Mackenzie King’s Liberals, keen to win support on the left, ended it in 1936. Or did they?

In fact, it lived on in spirit and in the Defence of Canada Regulations imposed under the umbrella of War Measures in 1939. This allowed the government to confiscate property, ban publications, intern inconvenient Canadian trade unionists, socialists, minorities and, most famously, more than 22,000 Japanese Canadians.

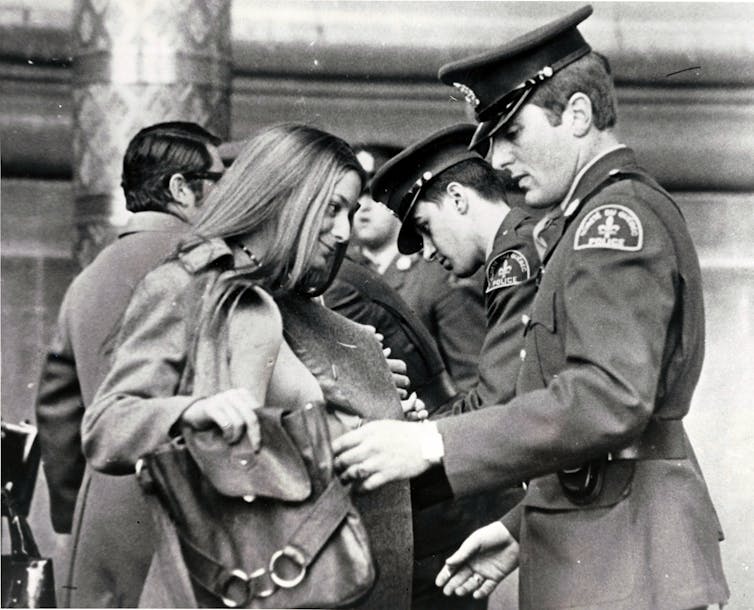

And this brings us back to October 1970. The invocation of the War Measures Act in 1970 was part of a long tradition. Prompted by two high-profile kidnappings and the assassination of Québec’s minister of labour and vice-premier, the government of Pierre Trudeau suspended civil liberties and enhanced police powers of arrest and interrogation.

Hundreds arrested in 1970

Across Canada — but most of all in Québec — hundreds were arrested, denied legal counsel and ultimately released, often without any explanation.

By and large, both in Québec and the rest of Canada, people were convinced then that the state had acted appropriately to quell an insurrection by a radical cell of Québec separatists. Only with time did many question the government’s actions, with some arguing that Ottawa’s case seemed far-fetched and self-interested. To this day, the imposition of War Measures stirs bitter memories in Montréal and Québec.

Emergencies Act replaced War Measures

Such memories led to a widespread move to close the books on War Measures, and in 1988 it was succeeded by the Emergencies Act, its kinder, gentler, Charter of Rights-friendly successor. Yet, as was the case in the 1930s, what seemed the death of the old bill was in many ways resurrected under another name. The Emergencies Act similarly gives cabinet the capacity to govern without almost any parliamentary oversight.

In the peculiar atmosphere of ambient anxiety fuelled by COVID-19, we once more hear the clarion call: an emergency situation demands extraordinary powers.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau mused about using the Emergencies Act for the first time to allow the government to, among other things, have total control over medical supplies. But the country’s premiers have since told Trudeau invoking the controversial law is unnecessary. Still, the Trudeau government has sought the right to impose taxes without prior parliamentary approval.

Thanks to vastly fortified means of surveillance via technology, the ability to regulate the lives of citizens can now be carried out on a microscopic level beyond anything imagined by Mackenzie King or Pierre Trudeau.

The Emergencies Act has a controversial legacy, one that historians have regularly critiqued and pointed out. Whether it’s the War Measures Act or Section 98, Ottawa’s top-down impositions often come at a hefty price. Canadians should remember that before granting their governments sweeping — and not easily revoked — powers.

The Wilson Institute for Canadian History — in partnership with Université Laval, McGill-Queen’s University Press and the Bulletin d’histoire politique — is hosting a conference Oct. 15-16 on the 50th anniversary of the October Crisis.![]()

Maxime Dagenais is the coordinator of the Wilson Institute for Canadian History and an adjunct assistant professor of history at McMaster University. Ian McKay is the Director of the Wilson Institute for Canadian History at McMaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.