Piecing together the rich history of the ancient city of Metaponto

BY Wade Hemsworth

December 13, 2017

One day he’s in jacket and tie, and the next day he’s down in the dirt. Spencer Pope could hardly be happier with his major new project in Italy.

Pope, an archaeologist and professor of Classics at McMaster, is working his way backwards in time from modern Italy through the Roman empire, going back nearly 2,600 years in total, to a period when the city of Metaponto was a major Greek settlement on the Mediterranean.

The area is now home to the modern town of Pisticci.

Pope and his team recently returned from their latest work in Italy, having made good progress after picking up the project from classical archaeologist Joseph Carter of the University of Texas at Austin.

Carter and his team had been working since the 1970s to gather, label and carefully store artifacts, having gathered tens of thousands in all, and now the McMaster team is continuing and expanding the work.

In Italy, Pope and his McMaster-led team split their days between meetings and fieldwork.

Through clues provided by shards of pottery and other remnants that continue to come to the surface, Pope, his colleagues and their predecessors have been developing a record of how people lived in the farming areas surrounding the coastal city, where the heel of Italy’s boot meets the arch.

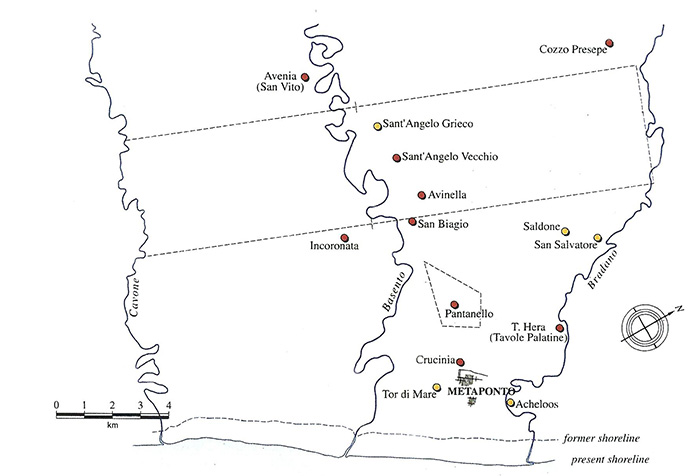

The project takes old Metaponto as its hub and seeks to understand more about 400 square kilometres of surrounding agricultural communities that fed into the city. The same grain fields continue to be farmed today, making it a much easier location to study than other settlements that have since been built over.

In the hands of experts, each found fragment can tell part of a rich story of how and where people lived over time. One shard, for example, was part of a disc that represented a woman’s face, a kind of gargoyle to ward off evil spirits.

Another is made and marked in a way that shows it to be a fragment from an everyday plate from Roman times, and another from the handle of an amphora that wealthy Greeks had used for wine or olive oil, possibly hundreds of years earlier.

Taken together and mapped using GPS, drone and photogrammetry technology, the pieces allow researchers from multiple disciplines to assemble a complex understanding of the evolving lifestyles, living arrangements and even politics of the time.

Still, Pope says, there is nothing as valuable as being there in person.

“Being out under the sun on the hillsides, seeing the relationship between the territory and the water helps you understand what might have attracted someone to a site,” he says. “It’s a skill and a sense that can only be created there.”

Pope is hopeful that in coming years the project will expand to take in McMaster researchers from several disciplines, including Engineering, Geography and Anthropology.

They could use imaging and 3D printing to make perfect replicas of broken shards and even to produce facsimiles of entire pieces, based on fragments.

“I feel very fortunate to be here at McMaster, where we have a broad university with experts in many different fields,” Pope says. “Our core skills here in Classics are Greek, Latin and ancient history, but we shouldn’t think of those as the limitations of the field, but rather the starting points.”

Pope and his team plan to return to walk the fields that extend for kilometres around the hub of Metaponto, to gather more pieces that will show them the best places to dig deeper in the search for the ruins of homes and places of worship, commerce and burial.

But none of it can happen without diplomacy. To be able to do the work requires developing the trust of government officials in Italy, who are naturally concerned about their antiquities, and of the farmers who may be leery of having an important discovery on their farms, a process that can lead to expropriation.

It helps, Pope says, that there is a healthy population of descendants of the modern town of Pisticci now living in Southern Ontario, who are proud to have a McMaster-led project revealing the historical importance of a place they love.

Pope and his colleagues tread as carefully and respectfully through their administrative work as they do through their fieldwork – that’s what the jackets and ties are for – and Pope says the blend is what makes the work so interesting.

“It’s one of the most satisfying things you can do when you’re working in archaeology,” he says. “You’re doing a lot of different things. One day, we’re meeting with the Superintendent of Heritage. The next day we’re in the field in t-shirts.”