Plague trackers: Researchers cover thousands of years to understand the elusive origins of the Black Death

Researchers at McMaster's Ancient DNA Centre studied more than 600 genome sequences of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague. (Image courtesy of the Museum of London Archaeology)

BY Michelle Donovan

January 19, 2023

Seeking to better understand more about the origins and movement of bubonic plague in ancient and contemporary times, researchers at McMaster University, the University of Sydney and the University of Melbourne have completed a painstaking granular examination of hundreds of modern and ancient genome sequences, creating the largest analysis of its kind.

Despite massive advances in DNA technology and analysis, the origin, evolution and dissemination of the plague remain notoriously difficult to pinpoint.

The plague is responsible for the two largest and most deadly pandemics in human history. However, the ebb and flow of these, why some die out and others persist for years has confounded scientists.

In a paper published Thursday in the journal Communications Biology, McMaster researchers use comprehensive data and analysis to chart what they can about the highly complex history of Y. pestis, the bacterium that causes plague.

The work was meticulously conducted by graduate student Katherine Eaton over the course of several years.

Millennia of genomes

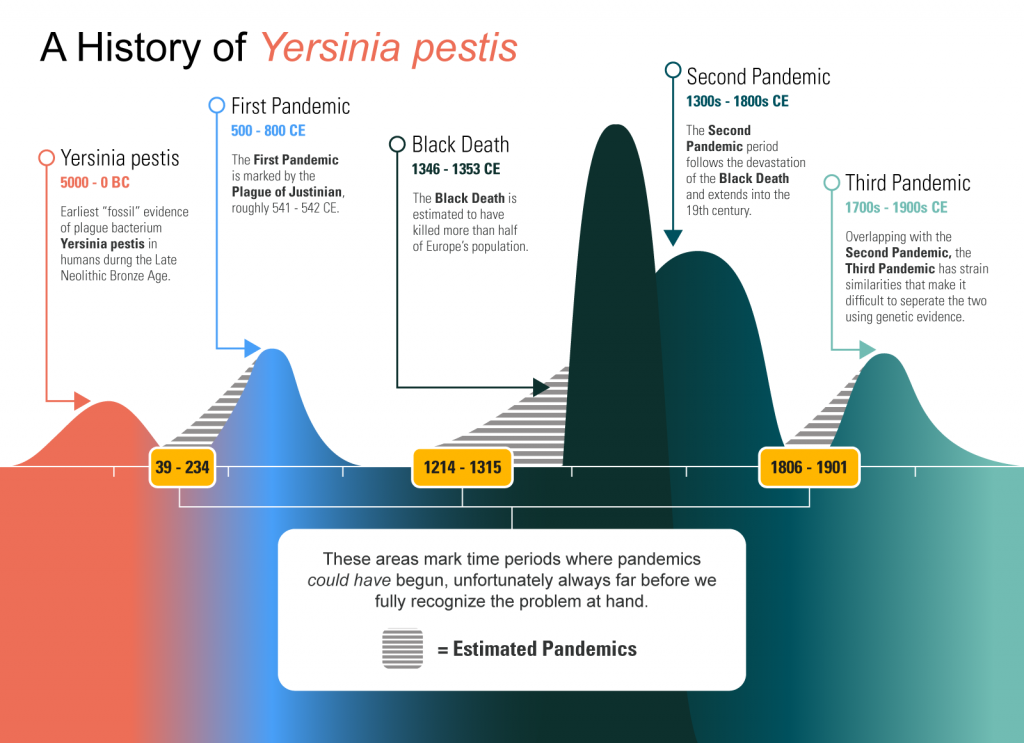

The research features an analysis of more than 600 genome sequences from around the globe, spanning the plague’s first emergence in humans 5,000 years ago, the plague of Justinian, the medieval Black Death and the current (or third) pandemic, which began in the early 20th century.

“The plague was the largest pandemic and biggest mortality event in human history. When it emerged and from what host may shed light on where it came from, why it continually erupted over hundreds of years and died out in some locales but persisted in others,” explains evolutionary geneticist Hendrik Poinar, director of McMaster’s Ancient DNA Centre. “And ultimately, why it killed so many people.”

Poinar is a principal investigator with the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research and Canada’s Global Nexus for Pandemics & Biological Threats at McMaster.

On the trail of Y. pestis

The team studied genomes from strains with a worldwide distribution and of different ages and determined that Y. pestis has an unstable molecular clock. This makes it particularly difficult to measure the rate at which mutations accumulate in its genome over time, which are then used to calculate dates of emergence.

Because Y. pestis evolves at a very slow pace, it is almost impossible to determine exactly where it originated.

Humans and rodents have carried the pathogen around the globe through travel and trade, allowing it to spread faster than its genome evolved. Genomic sequences found in Russia, Spain, England, Italy and Turkey, despite being separated by years are all identical, for example, creating enormous challenges to determining the route of transmission.

To address the problem, researchers developed a new method for distinguishing specific populations of Y. pestis, enabling them to identify and date five populations throughout history, including the most famous ancient pandemic lineages which they now estimate had emerged decades or even centuries before the pandemic was historically documented in Europe.

“You can’t think of the plague as just a single bacterium,” explains Poinar. “Context is hugely important, which is shown by our data and analysis.”

To properly reconstruct pandemics of our past, present, and future, historical, ecological, environmental, social and cultural contexts are equally significant.

He explains that genetic evidence alone is not enough to reconstruct the timing and spread of short-term plague pandemics, which has implications for future research related to past pandemics and the progression of ongoing outbreaks such as COVID-1