Prescription drugs in treated wastewater are making fish more vulnerable to predators

BY Michelle Donovan

December 5, 2017

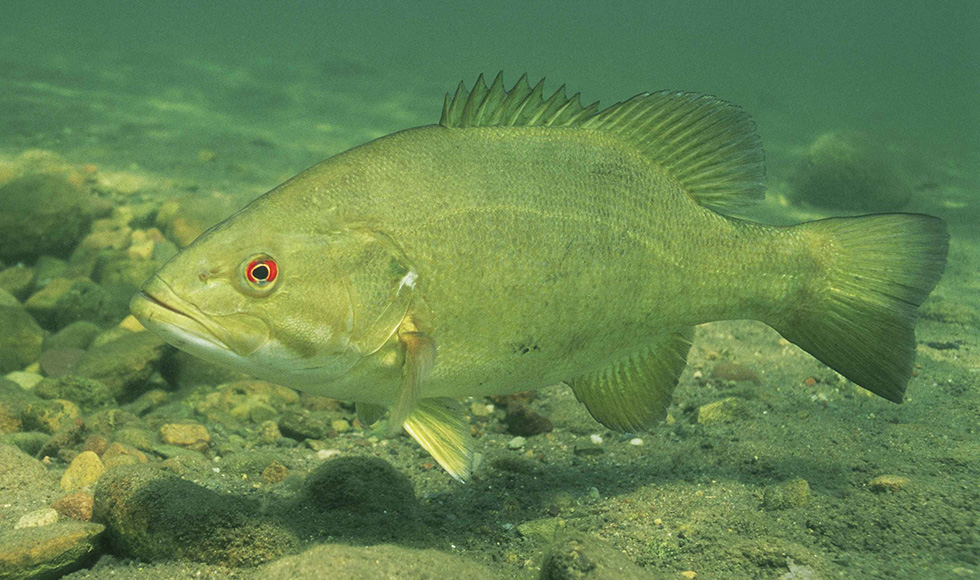

A team of researchers from Environment Canada and Climate Change Canada and McMaster University have found that fish living downstream from a wastewater treatment plant showed changes to their normal behaviour—ones that made them vulnerable to predators—when exposed to elevated levels of antidepressant drugs in the water.

The findings, published as a series of three papers in the journal Scientific Reports, point to the ongoing problem of prescription medications, personal care products and other drugs that end up in the watershed and the impact they have on the natural environment.

“Fish can be seen as the canaries in the coal mine,” says Sigal Balshine, a professor in the Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour at McMaster and one of the authors on the papers. “The fish that make their homes in the receiving waters downstream from wastewater treatment plants absorb these chemicals and therefore can be our water sentinels.”

For their research, the team caged gold fish at various sites in Cootes Paradise watershed—designated as a Great Lakes Area of Concern by an international environmental commission—and at a control site in Jordan Harbour, which is located between Beamsville and St. Catharines on the shores of Lake Ontario.

Their analysis found several commonly prescribed antidepressants, known as serotonin uptake/reuptake inhibitors, in the blood plasma of the fish that were caged in the Cootes Paradise Marsh, downstream from the Dundas Waste Water Treatment Plant.

The drugs, say researchers, increased the levels of serotonin in the fish, which in turn affected their swimming behaviour. In short, the fish caged closest to the source of the drugs were bolder, less anxious, were more willing to explore, and more active overall than the fish caged at Jordan Harbour.

Because the affected fish were less anxious, their altered swimming patterns could make them more susceptible to predators. They began moving again faster following a simulated predator attack.

“Taken together, our results suggest the fish downstream of waste water treatment plants are accumulating pharmaceuticals and personal care products at levels sufficient to alter neurotransmitter concentrations and to also impair ecologically-relevant behaviours,” says Jim Sherry, a research scientist with Environment Canada and lead author of the study.

Researchers also point to other molecular changes in the fish which point to drug induced injury to the liver and compromised lipid metabolism.

Sigal Balshine’s team also studies species diversity in urban water basins, like Hamilton’s Windermere Basin.

With an abundance of rivers, lakes and oceans, researchers suggest that most Canadians don’t appreciate the seriousness and need for safe water reuse.

“Over one billion people on our planet lack access to clean drinking water and a number of serious water borne diseases are caused by improper water treatment,” says Balshine. “Water treatment and reuse must be a top priority for municipalities, regions and countries and so understanding the impacts of water treatment on ecosystem function is necessary first step to ensure that we have a sufficient water supply, maintain our biodiversity and protect the health of our ecosystems.”

The study was funded by the Great Lakes Action Plan (Phase V) and the Build in Canada Innovation Program.