Protein shakeup: McMaster researchers’ discovery may unlock age-related illnesses

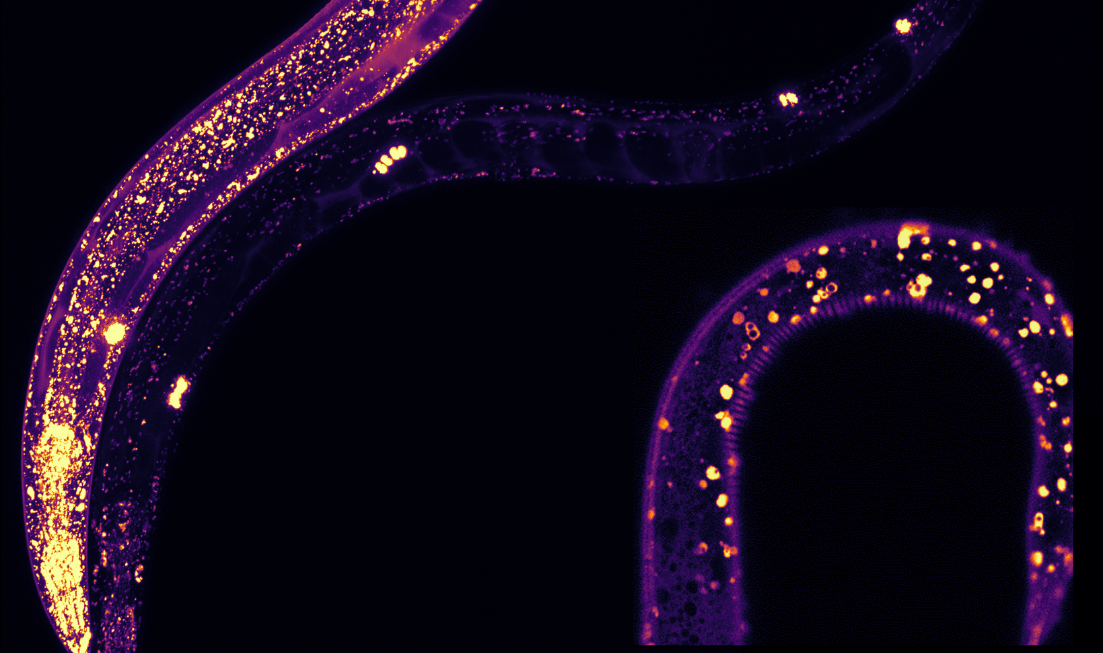

McMaster researchers studied how certain protective proteins, highlighted in this illustration by the purple and yellow dots, expressed in translucent C. elegans worms. They found it present in structures associated with lifespan, showing that these proteins keep cells healthier so they can function better for longer.

BY Andrea Lawson

October 18, 2024

McMaster University researchers have discovered a previously unknown cell-protecting function of a protein, which could open new avenues for treating age-related diseases and lead to overall healthier aging.

A class of protective proteins known as MANF plays a role in the process that keep cells efficient and working well, the research team found.

Their findings were published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Our cells make proteins and discard them after they perform their jobs. This efficient, continuous maintenance process is known as cellular homeostasis.

But as we age, our cells’ ability to keep up declines: Cells can create proteins incorrectly, and the cleanup process can become faulty or overwhelmed. As a result, proteins can clump together, leading to a harmful buildup that has been linked to such diseases as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

“If the cells are experiencing stress because this protein aggregation has started, the endoplasmic reticulum, which is where proteins are made and then released, gets the signal to stop making these proteins,” explains McMaster biology professor Bhagwati Gupta, who supervised the research.

“If it can’t correct the problem, the cell will die, which ultimately leads to degeneration of the neurons and then neurodegenerative diseases that we see.”

Previous studies, including one from McMaster, had shown that MANF protects against increased cellular stress. The team set out to understand how this happens by studying microscopic worms known as C. elegans. They created a system to manipulate the amount of MANF in C. elegans.

“We could literally see where MANF was expressed in the worms because they are translucent,” said Shane Taylor, who worked on the project for his PhD while at McMaster, and is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of British Columbia.

“We could see it in all different tissues. Within these tissues, MANF was present in structures known as lysosomes which are associated with lifespan and protein aggregation.”

The team discovered that MANF plays a key role in the cell’s disposal process by helping to break down the accumulated proteins, keeping cells healthier and clutter-free.

Increasing MANF levels also activates a natural cleanup system within cells, helping them function better for longer.

“Although our research focused on worms, the findings uncover universal processes,” Taylor said.

“MANF is present in all animals, including humans. We are learning fundamental and mechanistic details that could then be tested in higher systems.”

To develop MANF as a potential therapy, researchers want to understand what other players MANF interacts with.

“Discovering MANF’s role in cellular homeostasis suggests that it could be used to develop treatments for diseases that affect the brain and other parts of the body by targeting cellular processes, clearing out these toxic clumps in cells and maintaining their health,” said Gupta.

“The central idea of aging research is basically can we make the processes better and more efficient.”

“By understanding how MANF works and targeting its function, we could develop new treatments for age-related diseases. We want to live longer and healthier. These kinds of players could help that.”