Re-examining histories of Black and queer protest

Humanities Prof. Ronald Cummings, editor of a new book of Lillian Allen's poetry, talks about literary decolonization, queer Caribbean writing and the legacies and lessons of past Black protest.

BY Sara Laux, Faculty of Humanities

February 15, 2022

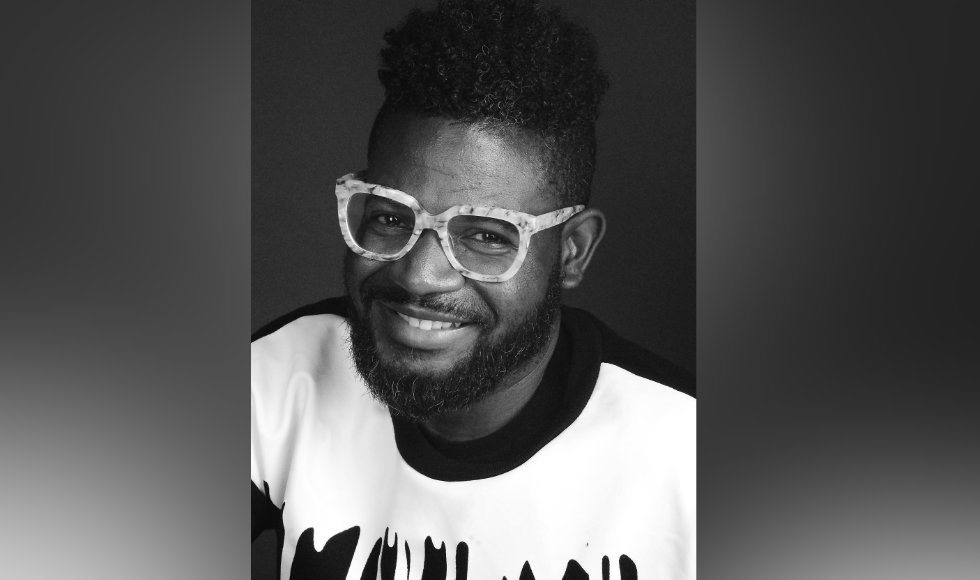

Ronald Cummings, associate professor in the Faculty of Humanities’ Department of English and Cultural Studies, came to McMaster in September 2021 from Brock University.

His work focuses on Caribbean literature and Black diaspora studies. He is the co-editor of The Fire that Time: Transnational Black Radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation (with Nalini Mohabir) and Caribbean Literature in Transition, 1970-2020 (with Alison Donnell). He is also the editor of Make the World New: The Poetry of Lillian Allen.

Here, he explains the focus of his research, his most recent work, and his “nerdy” love of working with archives and archival materials.

Could you tell me a little about your current research?

My research might be understood through three points of focus. All three of these might be traced, in some way, back to the transformative period of the 1960s, which was a time of important social change and social movements.

The first is literary decolonization. I have been thinking about shifts and transformations in the field of literary studies in the wake of political independence in different parts of the globe, including the Caribbean region, which has been central to my work. My recent co-edited book Caribbean Literature in Transition 1970-2020 is one historiographical study that has sought to grapple with that question, which is not a foreclosed one. I see decolonization as necessarily an ongoing, present question.

The second aspect of my work focuses on questions of sexual citizenship. My PhD work was on queer Caribbean writing, and that’s an area in which I continue to write and research.

Most recently, I’ve co-edited a special issue of the journal sx salon focused on “The Queer Caribbean” and last year I also co-edited an issue of the Journal of Canadian Studies focused on “Queer Canada” with Sharlee Cranston-Reimer – who is a graduate from English and Cultural Studies at McMaster.

The third strand of my research has been thinking about histories of Black protest. I have been researching the radical 1960s. Some of that is linked to my ongoing critical work on questions of queerness. 1969 was the Stonewall uprising. This is a narrative that we all think we know. I’ve been asking: How might we re-narrate that history with a focus on the intersections of blackness and queerness, and how might we also attend to queer historical narratives beyond the U.S. context?

I’ve also been working on another co-edited project with my colleague Nalini Mohabir, who is at Concordia. We’ve just edited a book called The Fire That Time: Transnational Black Radicalism and the Sir George Williams Occupation.

It seeks to recuperate the history of a 1969 two-week protest by Black students and their allies at Sir George Williams University, which is now Concordia University. We ask about the lessons and legacies of that history, particularly in another moment where we’re thinking in vital ways about the relationship between Blackness, Black Studies and the university.

What are some of the lessons we can learn from that history?

For one thing, I don’t necessarily see it as past history. During the 1960s there were similar protests and student occupations at Cornell, Brandeis, Michigan, Kent State and a number of other American universities, but this particular moment in the context of the Canadian academy has been marginalized and largely forgotten.

The Black students in Montreal were calling for fair grading—a call for inclusion, and for Black Studies to be part of the curriculum. Even today, not many universities in Canada have Black Studies programs. The questions those protesters were raising are still relevant.

Recently, a number of universities have started to announce Black Studies and Africana Studies minors, and have been focusing on recruitment of Black faculty – but presence doesn’t always mean welcome, as the story of 1969 teaches us. We need to be constantly vigilant about that, and to think about creating not just spaces with representative numbers, but also welcoming and decolonial spaces.

Part of my own welcome at McMaster has been through the work that is being done by the African and Caribbean Faculty Association of McMaster (ACFAM) — meeting a community of scholars, who have been telling new arrivals like me what to look out for, some of the resources that are available, and some of the spaces in which our work might help to effect change within the institution.

You’ve mentioned that part of that welcome is being in a place that is preserving Black archives.

McMaster has been doing the work of curating Black archives, like the Miss Lou archive, the Austin Clarke papers, the Tony Macfarlane collection — for me, as a researcher who does work on the Caribbean, it’s a generative space. It feels like it’s a space in which there are resources that can inform my work.

I’ve always been interested in questions of literary historiography, and some of that has just been the nerdy work of going to the archives, sitting with the archives, encountering things in the archives that I’ve then gone back and pursued.

Can you tell me a little about the book of Lillian Allen poetry that just came out?

Lillian Allen is overdue a collection of this sort!

It was great sitting with these poems and thinking about them and about the tremendous trajectory of Lillian’s work, and also having the opportunity to talk with her about the context of her work across the decades.

One of the things that was important to me was positioning Lilian Allen as a poet of transnational significance. She talks about the ways in which she’s often considered foreign, both in relationship to Canada, but also in a Jamaican literary context as well.

Her poems have been important for writing the landscape of a city like Toronto, but she’s also writing about the US, and about South Africa, particularly in the context of apartheid, like so many other poets of the Black diaspora. She’s writing about Nicaragua, she’s writing about Britain and empire. She is writing about Jamaica– I think these transnational questions are important in thinking about her poems and this work as a collection.

Has it been well received?

It has! It was on the CBC list of best poetry books of last year, which was a wonderful surprise.

It’s also been well received by my students. I had the pleasure of teaching it last term as part of a first-year course called The Written World.

Lillian Allen is consciously challenging us to think about the relationship between the world and the word — the ways in which the writer is reflecting on the world and reimagining the world through writing.

At the same time, she’s pushing against an understanding of her work solely in relation to a tradition of writing — she asks us to think about her poetry in the context of community in embodied and social ways.

What’s next?

I proposed a course which will be running in the fall called “Windrush Writing/Writing Windrush.”

Windrush was the ship that went from the Caribbean to London, bringing a whole generation, including writers, who remade Black cultural life in Britain.

Because I’ve been working with this archive, I’ll think with my students about the writing that emerged from the period of the Windrush migration to Britain, as well as more recent writings from the early 2000s that have been re-narrating those journeys.

We’re thinking through those histories, but also thinking through the resonances with the present.