How will tariffs affect Canada’s auto sector? Q&A with expert Greig Mordue

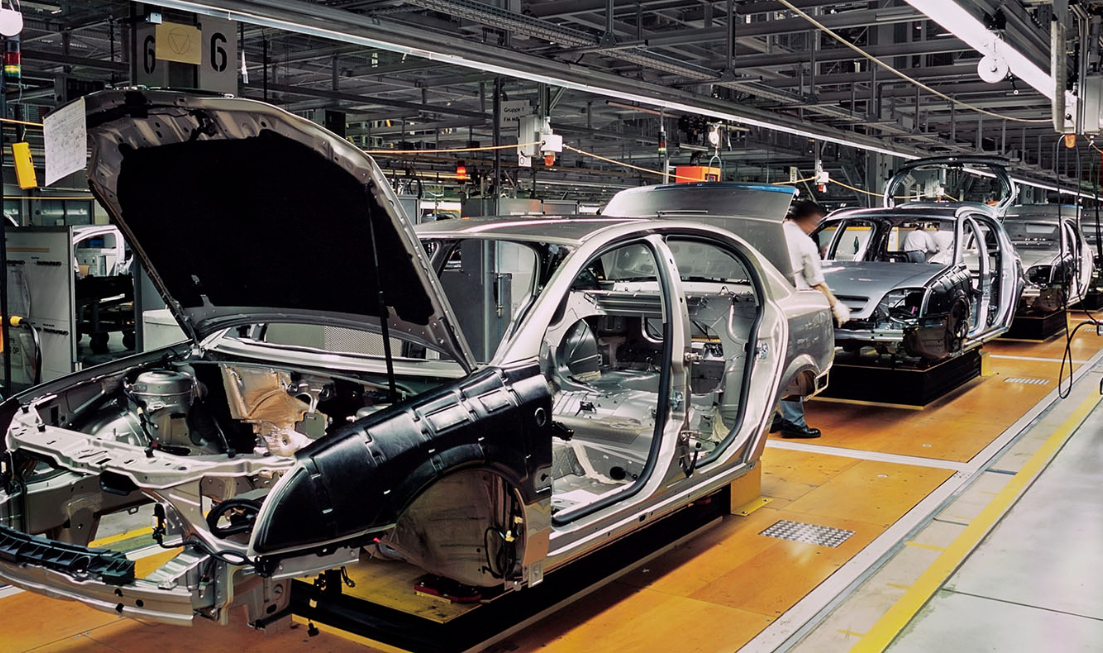

After decades of integrated North American automotive supply chain operation, Canadian auto production —and employment — faces a bleak future, expert Greig Mordue warns. (IStock image)

February 10, 2025

With the looming threat of U.S. tariffs, Canada’s automotive sector — one of its largest manufacturing industries — is particularly vulnerable due to its deep supply-chain integration with the U.S. market.

Greig Mordue, an associate professor at the W Booth School of Engineering Practice and Technology in the Faculty of Engineering, and the ArcelorMittal Dofasco Chair in Advanced Manufacturing Policy, provides his expert insights.

Greig Mordue, an associate professor at the W Booth School of Engineering Practice and Technology in the Faculty of Engineering, and the ArcelorMittal Dofasco Chair in Advanced Manufacturing Policy, provides his expert insights.

What will happen if the temporary reprieve from U.S. tariffs granted to Canada is not extended in March?

No one will be surprised to learn that this process is going to be extremely choppy. Each company, each country and each community will be affected. For example, Toyota is Canada’s top auto producer. It makes more than 500,000 vehicles per year in Cambridge and Woodstock, including the company’s highest selling Lexus models and the top-selling RAV4.

If you make half a million vehicles in Canada and you are confronted with tariffs of 25 per cent, you might expect cost increases of $5 billion or more annually. No automaker can absorb that. If tariffs persist, U.S. consumers will be forced to pay.

What happens over the long term?

Canadian auto production will drop and employment will fall. Absorbing — or deflecting — tariffs in the here and now is only the start. Even if the current flareup settles down and tariffs are not imposed, long-term damage has already been done.

The lingering threat of tariffs has already put — and will continue to put — a serious chill on non-U.S. automotive investment. The decades-long assumption that North American automotive supply chains are integrated has suffered a serious blow.

Whether it was his intention or not, President Trump’s threat of tariffs has already had the long-term effect of nudging investment to the U.S.

Why do automakers find this so difficult to manage?

Designing, producing and selling something as complex as a vehicle — and establishing a supply chain to do so — is incredibly difficult. A key policy underpinning automotive supply chains was established in 1965 when the Canada-U.S. Auto Pact was put in place. The Auto Pact gave us a framework for integrating North American automotive supply chains. It was subsequently affirmed via agreements like the Canada-U.S. FTA (1988), the NAFTA (1994) and the USMCA (2018).

Now, the industry is being asked to abandon a 60-year-old directive and to do it in a matter of weeks. It can’t be done.

Global supply chains exist as they do, and they have evolved as they have for a number of reasons. However, the main reason is this: They work.

A shift to local (i.e. U.S.) sourcing will be costly. If producing everything in the U.S. was cost effective, everything would already be made there.

If costs go up — and they will — those extra costs have to be borne somewhere. That “somewhere” is consumers. And because U.S. consumers buy more vehicles than anyone, U.S. consumers will bear those costs disproportionately; not just the direct cost of the tariffs, but because of the inefficiencies that lack of access to each company’s well-developed global supply chain will entail.

How do you see this shaking out?

We’re very, very early in the life cycle of the new Administration. So far, we have witnessed the president using executive authority — in this case, the U.S. International Emergency Economic Powers Act or IEEPA — to manage issues at that country’s borders.

We should brace ourselves for a whole lot more.

Traditionally, the IEEPA has been used to manage unusual or extraordinary threats to national security or foreign policy. Going forward, you can expect the U.S. president to continue to stretch the boundaries of executive authority.

The IEEPA is a convenient tool, and the president will use it to reposition U.S. relations; not just with Canada and Mexico, but with the EU, Japan, Southeast Asia and others.

Moreover, instead of limiting the IEEPA to traditional threats to national security and foreign policy you can expect that the president will use it to deal with a host of irritants — trade deficits, currency manipulations, taxes deemed discriminatory in nature, other country’s procurement policies, longstanding bilateral and multilateral trade agreements now thought of as unfavourable.

In other words, this approach is likely to grow in terms of the number of countries that are targeted and the stated reasons for targeting them.

What does this mean for the proliferation of new technologies and the competitiveness of the North American auto industry?

On top of the imposition of tariffs, the new administration has indicated that it will suspend mandates, targets and other support measures for the manufacturing and purchase of electric vehicles.

However, the combination of closing the border and discouraging the influx of new technology (including electric vehicles and drivetrains) will not stop the rest of the world’s auto industry from moving forward. However, it will curtail the development — and ultimately the competitiveness — of the North American auto industry.

My research shows that China is now responsible for more than 50 per cent of the world’s automotive patents. The U.S., by contrast, generates just 8 per cent. Canada is responsible for about one-third of 1 per cent.

Erecting a wall around North America and its auto industry — and protecting it from competition — will eventually consign the North American industry to the status of global laggard.