‘The momentum has sustained itself’

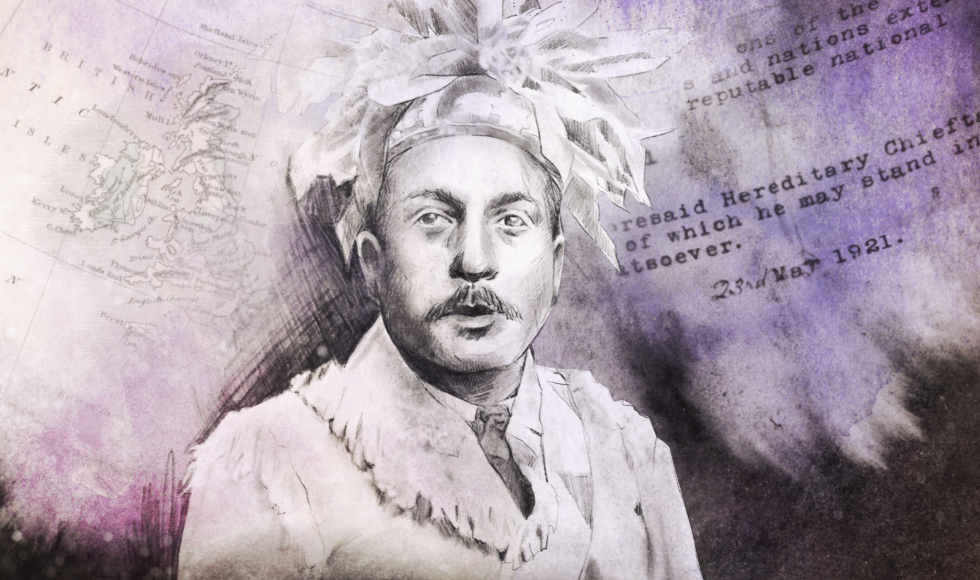

A still from Deskaheh, the Resurgent Histories Lab's most recent short animation, which has won awards at major international film festivals.

BY Sara Laux, Faculty of Humanities

June 26, 2025

Allan Downey has had a busy few months. For one thing, he has a new baby. He’s also writing a book. And his latest short film project, Deskaheh, has been making the rounds of film festivals, conferences and community events, winning awards and sparking important conversations.

Deskaheh tells the story of Deskaheh Levi General who, in the 1920s, travelled from Six Nations of the Grand River to Geneva to advocate for Haudenosaunee sovereignty at the League of Nations (“Deskaheh” is a title given to hereditary chiefs of the Haudenosaunee).

Downey, the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous History, Self-Determination and Nationhood, co-created Deskaheh with three Indigenous McMaster students — co-directors Tekenikhon Doreen and Jersee Hill, and producer Kira Gibson.

Professor Rick Monture, in the Department of English and Cultural Studies, served as a producer and key research consultant to the animation. The film was animated by Vancouver-based artist Saki Murotani, who also animated Downey’s first short film, the award-winning Rotinonshón:ni Ironworkers.

The launch of Deskaheh in November 2024 also marked the official launch of Resurgent Histories: The Indigenous History Lab at McMaster University, a youth mentorship project directed by Downey that aims to make Indigenous histories accessible to a public audience through digital animations.

We caught up with Downey to find out more about Deskaheh and its reception, as well as what’s next for the Resurgent Histories lab.

You’ve been presenting Deskaheh at film festivals and conferences – how’s that going?

When we first screened the film in November of 2024, we expected maybe 50 people to show up and we had more than 300. It’s been like that ever since that day – the momentum has kind of sustained itself.

We’ve already shown it at four international film festivals: the Toronto Short Film Festival, the Toronto Animation Arts Festival International, the BIPOC PoP Animation Festival, which was held at the University of Texas at Austin, and the Quetzalcoatl Indigenous International Film Festival in Oaxaca, Mexico.

We’ve won two major awards so far, which was both unexpected and exciting. At the BIPOC PoP Film Festival we won the Best Animated Documentary award, and at the Quetzalcoatl Indigenous International Film Festival, we won Best Music in a Short Film. We were fortunate to have partnered with the Six Nations Women Singers and singer/songwriter Logan Staats who contributed music for the film, and I’m thrilled that their work was recognized in this way.

Besides the film festivals, we’ve been touring the film quite a bit. I went to the University of Northern British Columbia to screen it, it was also shown at the University of Buffalo Storytellers Conference, and at the Woodland Cultural Centre in Brantford as part of a conference and a museum exhibit – it’s really making the rounds.

The international response to the film was something I didn’t expect – I didn’t see the animation going to Mexico for a film festival and I didn’t see us winning an award in Austin, Texas. To have the story shared at so many different international venues and in these prominent ways– especially in the US– has been a nice surprise. We were hoping to take the story beyond borders, and it’s really done that.

What’s the reception for the film been like?

The reception has been terrific. These films were always about public engagement, about reaching out beyond our academic audiences and speak to the public with something accessible.

It’s been uplifting and encouraging to get the story of Deskaheh out there in the public sphere – it’s led to fruitful discussions within Indigenous communities and it’s been an exciting endeavour to engage in conversations around how we remember our histories and interpretations of those histories – what do we do with them? How do we act on them?

The film has been a springboard for conversations about inter-Indigenous politics or Indigenous community relationships, which has been both inspiring and thought-provoking to be a part of. I’ve appreciated the opportunity to engage in and witness those kinds of discussions – they’ve been a lot of fun.

A lot of the public conversation has been along the lines of not knowing this history– often, the comment is ‘why don’t we know this’– but when we show this film in Haudenosaunee communities, it’s been spurring rich conversations, because these community members have the cultural scaffolding to be able to discuss it in detail– they’re the PhDs of this kind of information.

It’s been enlightening to witness the conversations that have resulted from screening the film, conversations that talk about political processes or the continued impact of Deskaheh’s story today – it’s still measurable, the impacts of this story are still able to be seen and witnessed.

There are some nuances to how this particular film has been received, though.

True. In the public sphere, stories that centre Indigenous pain and trauma tend to be popular among audiences, but there are also stories that are told from our truths and our histories that are not part of that kind of voyeurism. It’s not what defines Indigenous history.

We can engage in enlightening discussions about Indigenous politics all we want, but public audiences generally aren’t equipped or interested in those stories. Audiences want to learn about residential schools or violent encounters– which of course, is important– but these layered political discussions and histories about self-determination and sovereignty just aren’t part of the popular interest yet, it’s not how Indigenous history has been framed to audiences in the past.

What is deemed to be not only important, but an acceptable form of entertainment, relates to discussions about how we perceive and engage with Indigenous stories – and often they’re stories of pain and trauma. Part of the goal of this film project is to push back against that.

Students have been an integral part of this project. Can you talk about that experience?

It’s been exciting to see our students, especially Tekenikhon and Jersee, launching into things like filmmaking and the mentorship activities that have occurred since the release of the film, supported by professor Rick Monture and Indigenous Studies– they’ve learned how to give a public talk, how to do media interviews, and how to present to academic audiences.

For undergrads, this isn’t a standard research experience. When Tekenikhon presented the film at the University of Buffalo, the whole crowd gave her a round of applause, which was great to see.

Tekenikhon has since presented the film in her community of Tyendinaga, at academic conferences, and even in front of 200 principals and vice-principals from the Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board. She’s now working in a couple of positions here at Mac, and Jersee, who has also done several academic talks related to the film, is off to do a combined MA/PhD program at York.

It’s my hope that their experience in the lab might contribute, in some small way, to the incredible trajectories they’ve set for themselves as scholars and leaders in their communities and beyond. They are really special and I was so fortunate to work with them.

What’s next?

We’re waiting to hear back from another couple of big film festivals about Deskaheh, but I’m also launching a third film project.

The ironworkers project led to Deskaheh, and now I’m starting a project in British Columbia with my own community. [Downey is Dakelh, from Nak’azdli Whut’en, Lusilyoo clan.] We’ve had several meetings about that project, and we are in the early stages of forming this third project and getting it launched.

We’re leaning toward telling the creation story of our community. The two projects that I’ve done so far have been very recent Indigenous political histories, but this one goes back to the creation of our community, so it’s a much older history that we’re hoping to tell.

You can watch Deskaheh on YouTube. Find out more about the Resurgent Histories lab at their website.