The moms are not alright: How coronavirus pandemic policies penalize mothers

The coronavirus pandemic has added to the workload and stress of mothers. Photo by Shutterstock

BY Clifton Van Der Linden, Faculty of Social Sciences

September 4, 2020

Following her recent installation as Canada’s first female finance minister, Chrystia Freeland was quick to acknowledge that a promotion such as hers was a rarity for a woman in the era of COVID-19.

“The economic challenge created by the coronavirus is hitting women particularly hard,” said Freeland in a media scrum following her appointment. “It’s hitting mothers particularly hard. We are seeing women’s participation in the workforce falling very sharply.”

Freeland’s comments echo mounting evidence of the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women around the world.

Women pushed out

A recent report from the Royal Bank of Canada found that women’s participation in the Canadian labour force fell by 4.7 per cent between February and May. There are multiple factors that have contributed to what has been dubbed the “shecession,” but childcare obligations are one of the most frequently cited. During the same period, employment among women with toddlers or school-aged children fell by seven per cent, whereas men with children in the same age groups only saw a decline of four per cent.

The evidence indicates that in households with children, the ramifications of shelter-at-home measures — which shuttered schools and child-care centres across the country while at the same time prohibiting families from soliciting support with child care from anyone outside the home — have fallen disproportionately to women.

Widening the gap

In the middle of an economic crisis where all child-care supports are suddenly withdrawn, parents cannot be faulted for reaching the difficult but ostensibly rational conclusion that the higher income earner should remain in the workforce. But the pervasive gender gap in earnings, which sees women make less on average than men, means that a man’s career is generally favoured in this calculus.

In addition, it’s not clear that the difference in earnings between men and women always determines how child-care obligations are allocated. Research has shown that, even in cases where women are the primary breadwinners in a household, they assume more of the household duties.

But employment statistics are just the tip of the iceberg. Not every household with children in Canada had a parent leave the workforce in order to tend to their children during the pandemic. Many Canadian families with young children at home have had to to balance full-time jobs and full-time child care. Parents have had to take on additional homeschooling responsibilities. All Canadian families, regardless of employment, have had to do more with less. But how has that workload been distributed?

In a recent study published in Politics & Gender, my co-authors and I sought to better understand how increased child care obligations during the COVID-19 pandemic were shared between women and men in Canada.

Drawing on findings from the COVID19Monitor.org initiative, an ongoing public opinion research study by Vox Pop Labs on social impacts of the pandemic, we found striking disparities in Canadian households when it came to the self-reported number of hours spent on child care by women and men even before the pandemic. These disparities are significantly exacerbated by government responses to COVID-19.

Vox Pop Labs surveyed 4,070 Canadians over a two-week period in late April and early June regarding the number of hours they spent on various tasks in an average week before the pandemic compared to during the pandemic.

Both men and women in Canadian households with children under 15 reported spending an average of 39 per cent more time on child care during the pandemic. So, at least in terms of the proportional increase in hours spent taking care of the kids, men and women seem to have rolled up their sleeves in equal measure (although men are known to overestimate their respective contributions to child care).

But this measure belies a massively uneven distribution of child care obligations between men and women in Canada prior to the pandemic, which set the conditions for even greater disparity once the pandemic hit.

Tracking child care

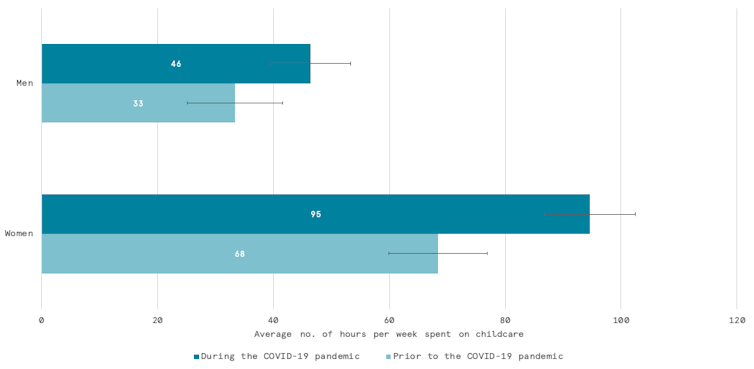

Even before COVID-19 triggered shelter-at-home measures, women with children at home reported spending more than twice as many hours on child care than men. Men reported an average of 33 hours per week spent on child care prior to the pandemic compared to 46 hours during the pandemic. Women reported spending 68 hours on child care on average in a given week before COVID-19 struck, and 95 hours thereafter.

To put things into perspective, these findings suggest that the average Canadian mother spent 13.5 hours per day on child care in late April and early June — roughly equivalent to the average waking hours of young children. While the sample includes stay-at-home-parents, who already spend the majority of their waking hours on child care, it also includes women who report being employed full-time. Working full-time hours coupled with full-time child care would theoretically allow for just 2.5 hours of sleep per night.

Obviously, this is untenable. Something has to give.

Alarming impacts

These findings are some of the most alarming yet when it comes to measuring the impact that the pandemic-related measures have had on mothers in Canada. They show that Canadian women with children at home have taken a hit to their mental health when compared with their male counterparts, which comes as little surprise given the circumstances.

Once the pandemic begins to subside, the focus on economic recovery must take stock of the gendered implications of emergency measures, particularly for women in households with young children. This is essential if we are going to make up for the uneven burden shouldered by Canada’s mothers during this crisis.

Clifton van der Linden, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Director of the Digital Society Lab, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.