Three strikes: Why today’s labour movements will be studied for years

It’s unusual to see autoworkers' unions Unifor and the UAW negotiating at the same time, says Labour Studies professor Stephanie Ross.

BY Matt Innes-Leroux

September 26, 2023

Labour unrest has been at the forefront of Canadian news through 2023 — federal public servants, port workers, grocery workers, and TVO staff all launched high-profile strikes — and there are no signs of job action stopping, with teachers in Ontario and public sector workers in Quebec holding strike votes this fall.

Unifor workers and Ford Canada reached a tentative agreement Tuesday, Sept. 19, averting a strike by 5,600 workers at the automaker after negotiations went past the deadline. With 54 per cent of Ford workers voting to ratify the agreement over the weekend, Unifor is bargaining with General Motors next.

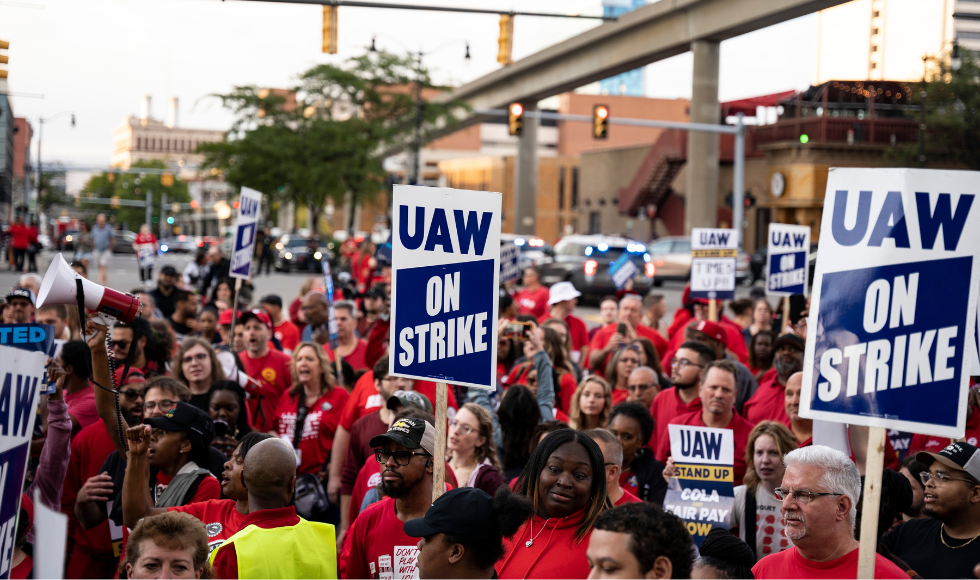

In the U.S., the United Auto Workers union began its first simultaneous strike against General Motors, Ford and Stellantis last week.

We spoke to Stephanie Ross, associate professor in McMaster’s School of Labour Studies, about auto industry negotiations, the state of the labour movement, and what to expect moving forward.

How does the UAW strike in the United States complicate negotiations with the automakers in Canada?

The UAW targeting all three Detroit manufacturers at the same time really introduces a level of uncertainty in these negotiations in Canada because all three of those companies are attending to what’s happening in the United States.

It’s very unusual to have Unifor and the UAW negotiating at the same time. We haven’t seen that for 20 years and that was in the depths of the 2008 recession where both unions made significant concessions to save the auto companies. In the past, the UAW acted as a downward drag on Canadian contracts. But now, if the UAW gets better deals than Unifor, it might cause some significant discontent here. We can see from the very narrow margin with which Ford workers approved the tentative agreement that many Unifor members might think that if they had held out longer they might have gotten more. So the timing of the other union’s settlements can really change the bargaining conditions and the mood of the membership.

But the most unpredictable and interesting element is the UAW’s decision to bargain and strike all three Detroit automakers at the same time. It’s typically been the union’s strategy to try to pick the company where they think they can get the best deal, bargain with them first, and then spread the pattern to the others. If one company made a certain deal, then it was possible for the others to agree to something similar. This time, the UAW is making the companies compete very directly to offer the best deal to the union as soon as possible to avoid more disruption to their operations. It’s a reversal of the race to the bottom.

As an observer, as things play out it seems the automakers might want to settle in Canada before they do in the United States, but that could lead to some discontent here if the U.S. deals look better.

How does the industry’s transition to electric vehicles affect this round of negotiations?

The transition to EVs is something that’s very much on the minds of the negotiators at Unifor. On the one hand, there is excitement about new investments and the prospect of long-term sustainability in the industry, On the other hand, there are concerns about the industry having a smaller footprint in the short run. So that means the union is trying to find ways to transition the most senior employees who won’t play a role in EV production to retirement.

Pensions were a huge issue at Ford Canada negotiations. Unifor’s bargaining team said it was as important to them as wages. That’s partly because they realize they’re going to need good early retirement packages to transition people out if the companies do have a smaller footprint.

There is also a lot of competition from non-union and anti-union players in the EV market, particularly in the United States. Some observers think that if the UAW gets the ambitious collective agreement they’re fighting for, it will make the Detroit Three uncompetitive.

But that outcome depends on labour market conditions where there’s a lot more unemployment and people feel vulnerable in their jobs. If we don’t have a big return to unemployment, if we still have a labour shortage, then the UAW’s agreements could start to put upward pressure on Tesla and the other lower cost, non-union automakers. If those companies want to retain scarce workers or prevent unionization, they’re going to need to match union contracts.

A recent Gallup poll found 75 per cent of Americans were siding with the UAW. Why is support so high for unions right now?

The UAW is getting support from the broader public in a way that I think no one could have predicted. Fully 75 per cent of Americans side with the UAW and just 19 per cent with the auto companies – that’s unheard of. One aspect of this is auto workers aren’t so much better off than other working-class Americans – that’s how degraded their jobs have become. So it’s easier to side with them now than resent them.

But the other aspect is that the UAW has captured the mood of working people in the United States. They’re trying to articulate a vision for an economy that rethinks the role of working people and what they are owed for their labour.

The UAW is explicitly framing their bargaining as in the public interest and calling on other workers to be confident and ambitious. It’s not just about their contract or their members. It’s very different, exciting and unlike anything we’ve seen from the UAW since at least the 1970s.

There’s so much economic uncertainty right now – food prices, inflation, housing costs – is economic instability something that emboldens the labour movement and drives action or does it make workers more cautious and hesitant?

That depends on the kind of instability. Rising unemployment will probably reduce the kind of labour militancy we’re seeing to some extent. But the instability driving militancy right now is inflation, and that is going to continue driving workers because they feel they’re falling behind. Real wages have been falling for decades and until recently, workers haven’t had an economic environment where they had the leverage to push back.

Workers are going to fight while the getting is good. I think that’s why we’ve seen this real intense upsurge, because people know this moment may not last. They are going to try to extract as many improvements as they can while the conditions are good for doing it. You just have to look at the slim margin in the Ford vote to see how much workers’ expectations have increased – this is the best agreement we’ve seen in the sector for many rounds of bargaining, and in this moment it was not seen as enough by 46 per cent of the members.

How long these conditions will last is an open question. There’s little doubt that corporate leaders and policymakers are trying to deflate the economy and return to a situation with higher levels of unemployment. Most people won’t say this out loud, but they are doing that because they know that unemployment will discipline workers’ expectations and make them feel more fear.

But labour shortages aren’t just going to evaporate with higher interest rates. Because we also have demographic changes happening around us. The baby boomers are in their retirement years, Generation X and the generations that followed are smaller. The labour supply is not going to come back to what it was in the post-war years.

How did the pandemic help reinvigorate the labour movement?

The experience of the pandemic has made people really rethink how much they’re willing to sacrifice for jobs and their employers. Workers are much less likely to put up with bad working conditions, and there’s a generational component to that as well. Generation Z are much less tolerant of working conditions they consider to be unfulfilling, and that generation is heavily involved in this new militant labour movement. They are leading the organizing drives at Starbucks in the United States, for instance.

When the pandemic first began, I thought it could wake up the labour movement. The health and safety dimensions of this crisis were so clear, and workers who refused to work in unsafe conditions – which is their legal right – were not supported by government inspectors. I thought that failure to protect workers’ health could be a moment for union mobilization, but it wasn’t. But it just took time. The pushback didn’t happen right away, but the last two years have really delivered.

Right now, it’s like being a labour studies scholar in the 1940s. Everyone’s just come home from the war and is fighting to establish a new labour movement and new regime of labour rights.

The labour movement is leading conversations about what kind of society we want to have in a very public way, not just in negotiating rooms where nobody can see.

I think we can point to three major recent strikes — the UAW, the Hollywood strike by the Writers’ Guild and SAG-AFTRA, and CUPE’s Ontario education workers in Fall 2022 — that all speak to these issues in a way that is clearly resonating with the public.

As an academic studying the labour movement, how exciting has this period been for labour studies as a field?

There’s no question that this is a moment where working people and workers’ movements are making waves. I haven’t seen this level of mobilization, mood of determination, and willingness to push the boundaries of what is considered “normal” labour relations since the 1990s.

That was the decade that fuelled my academic interest in the labour movement, because I was also a participant in the labour movement. My own personal formation as a union activist was organizing walkouts for the Ontario Days of Action against the Harris government. That was an unprecedented three years of political strikes against the provincial government and its implementation of neoliberal policies, cuts, attacks on workers and on other social sectors. But then things went quiet for a long time and the labour movement really struggled over the next twenty years.

This period is going to be looked at for a long time to try and unlock the strategic thinking behind how people have been organizing and the reasons why these demands, in this moment, are resonating so much with the public.

How can the labour movement keep building on this momentum?

How does this labour movement upsurge translate into other kinds of change, like political change? We don’t know. Because when we turn to politics we’re going to bring some clouds into the story.

We see remarkable unity around union action and economic struggles, especially in the United States where the UAW and Hollywood creative workers have off-the-charts levels of support. Support for strikers has strong in Canada but it’s more modest, which points to more division here over the role of unions.

But there’s a level of political polarization that remains. There are working-class people who align themselves politically with parties that are not historically or presently advancing very pro-worker agendas, despite what rhetoric they may use. Workers are embracing their right to strike but also embracing politicians who would restrict that right.

There’s a disjuncture there and it’s going to puzzle people for some time.