Using truth to confront atrocity

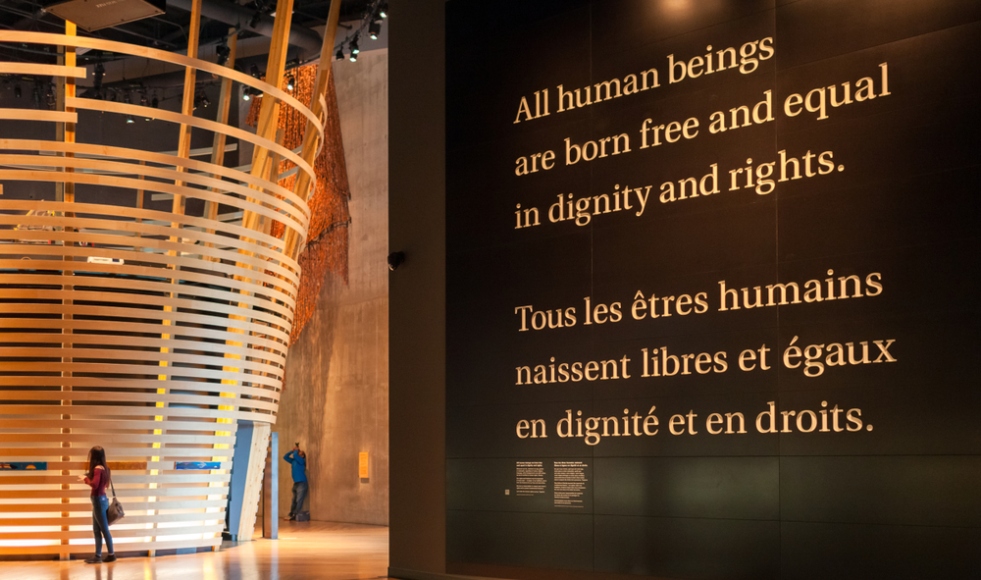

The Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg. Photo by Shutterstock/Salvator Maniquiz

BY Sara Laux

January 22, 2020

“Dad, why do you always talk about bad stuff?”

Bonny Ibhawoh’s 12-year-old son asked him that shortly after a news report on torture, genocide and war crimes. As he’s done with many international human rights issues, Ibhawoh had been providing commentary on these situations for media.

For Ibhawoh, the new Senator William McMaster Chair in Global Human Rights, “bad stuff” is an occupational hazard of working in human rights: he’s built a career on studying societies at their very worst. As an on-the-ground human rights practitioner with the Danish Institute for Human Rights and the Carnegie Council for Ethics and International Affairs, he worked in South Africa, Sudan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Liberia, and Sierra Leone as they recovered from national conflicts.

For Ibhawoh, the new Senator William McMaster Chair in Global Human Rights, “bad stuff” is an occupational hazard of working in human rights: he’s built a career on studying societies at their very worst. As an on-the-ground human rights practitioner with the Danish Institute for Human Rights and the Carnegie Council for Ethics and International Affairs, he worked in South Africa, Sudan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Liberia, and Sierra Leone as they recovered from national conflicts.

Now, as a legal historian, professor and policy advisor, Ibhawoh has published widely, worked with organizations like the UN and the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, and taught at universities in North America, Europe and Africa.

But there’s another side to human rights work – one that, at this point in his career, with his son’s question echoing in his ears, he’s eager to explore: in the aftermath of civil war and human rights abuses, how do societies begin to heal? And what can be learned from the efforts of countries that have tried to guide the healing process?

Restorative justice is a key concept for the next phase of Ibhawoh’s work. Unlike retributive justice – think war crimes tribunals, lawyers, punishment and incarceration – restorative justice seeks to heal both victim and perpetrator, and includes initiatives like truth and reconciliation commissions, memorials and museums, and public apologies.

“The philosophy of restorative justice is that if I dehumanize you, even in punishment, I ultimately dehumanize myself,” explains Ibhawoh. “This approach acknowledges that the only way that society can move forward is if, in bringing justice, the humanity of the perpetrators and the broader needs of the society are considered along with the needs of the victims. The focus is on restoring broken relationships while repairing the harm caused by violations.”

Ibhawoh’s first major project from the perspective from restorative justice is focused on studying truth commissions across the world, analyzing ones that have occurred and interviewing participants to assess, five or 10 years afterwards, whether the commissions have done what they set out to do.

Working with research colleagues and a network of graduate students across the world, Ibhawoh plans to build a database of truth commissions as well as develop a list of best practices for countries thinking of establishing truth commissions in the future.

With more than 67 national truth commissions established worldwide since the 1980s, and a growing global interest in the restorative justice model, Ibhawoh’s findings are going to be key for future peacebuilding.

“Truth commissions come in all shapes and sizes – some emphasize justice, like reparations. Others emphasize memorialization and acknowledgement, like we saw with the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission. No one size fits all,” Ibhawoh says.

“Our goal isn’t to say, ‘This is the best,’ but to think about what has worked. If this is a model that communities and nations are going to adopt, then we need to have an understanding of best practices of all the possibilities.”

Restorative justice isn’t just for nations, Ibhawoh says – it’s a model that’s used in the criminal justice and education systems as well. Ultimately, he’s planning for to expand the scope of his research into restorative justice beyond academia.

“More countries, more communities, and more schools are opting for restorative justice as they begin to recognize the limitations of the classic retributive justice model,” he says. “My hope is to provide a platform not just for expert scholars, but also practitioners, educators, attorneys and community stakeholders to come together and think through these issues.”