What the connections between Bertrand Russell and J. Robert Oppenheimer can reveal about the uneasy relationship between science and politics

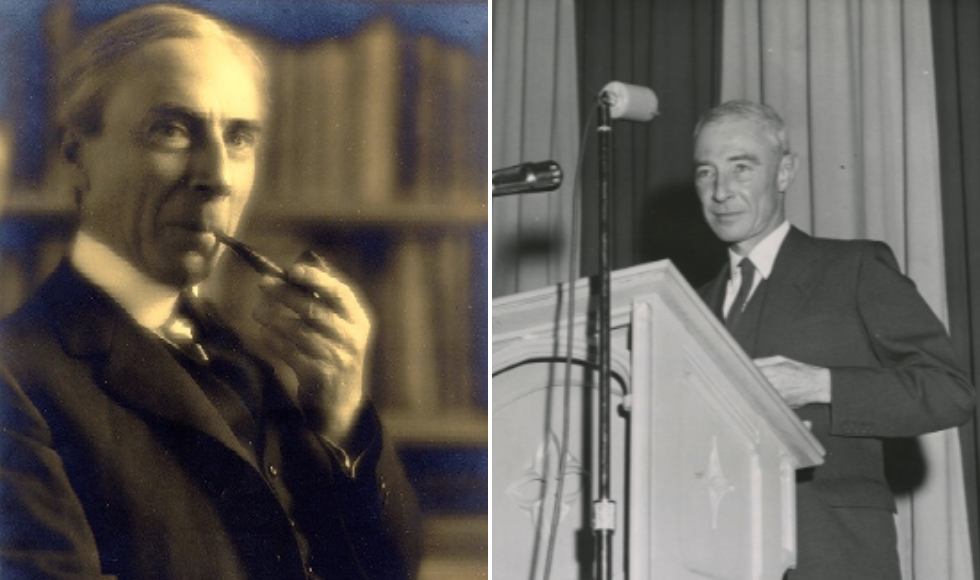

(Left to right) Bertrand Russell. Photo courtesy The Bertrand Russell Research Centre. J. Robert Oppenheimer delivering a lecture at McMaster in 1962. Photo courtesy the McMaster University Library.

BY Sara Laux

October 4, 2023

“I remember how [Alfred North Whitehead] would pause with a smile before a sequence of theorems and say to us, ‘That was a point that Bertie always liked.”

For all the years of my life, I have thought of this phrase whenever some high example of intelligence, some humanity, or some rare courage and nobility has come our way. For those of my generation, our world would have been far emptier of these great qualities without your presence and your work.”

So wrote J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb” and director of the Manhattan Project, to Bertrand Russell, one of the 20th century’s towering intellectuals and a prominent opponent of nuclear proliferation, on the occasion of Russell’s 90th birthday in 1962.

Read about Bertrand Russell’s life and work on the Bertrand Russell Research Centre’s website

A surprising correspondence, perhaps? What could the two possibly have in common?

The release of this summer’s biopic Oppenheimer has had the researchers at McMaster’s Bertrand Russell Research Centre thinking about the connections between Russell and Oppenheimer — and while their direct correspondence is, in fact, limited to a few letters, their intellectual connections and their individual lives provide some interesting insights into the years following the detonation of the first atomic bombs in 1945.

In this Q and A, Kenneth Blackwell, Russell’s original archivist, Andrew Bone, the Russell Centre’s senior research associate, and Nicholas Griffin, the Russell Centre’s Library Scholar in Residence, reflect on the contrasts between the two — and what renewed attention on this part of history can teach us today.

I understand that Russell reached out to Oppenheimer to join an international group of scientists whose goal was to mitigate the ongoing hazards of nuclear weapons – can you tell me about that?

KB: There are two. One was inviting him to come to a conference in India in 1956, which didn’t end up happening [because of the Suez Crisis] and another for him to go to the first Pugwash Conference in Pugwash, Nova Scotia.

AB: Pugwash was a movement that flowed out of what became known as the Russell-Einstein manifesto, which was a declaration by a group of very eminent scientists — most of the Nobel Prize-winners — that spoke of the dangers of nuclear weapons and called for the peaceful resolution of world conflicts.

Russell’s idea was not only that scientists were well equipped to understand the technical aspects of nuclear weapons, but also that a scientific outlook would enable them to consider these issues, despite political disagreements, in some kind of dispassionate way. Due to that capacity, he believed that this would be a way to slowly get to agreement on some of the major issues of the day, like banning nuclear weapons tests.

At this time, both Russell and Oppenheimer were thinking — as they had been for some years — about bolder steps, along the lines of world government — establishing an international body that would have far more authority than the United Nations and a monopoly on nuclear weapons and other weapons of war.

They were, politically, quite close, supporting disarmament talks and negotiations, and world government as the ultimate solution for taming the “two scorpions in the bottle”— Oppenheimer’s analogy for superpower rivalry in a nuclear age.

So what happened?

NG: Oppenheimer refused to go. He wrote to Russell, “I am somewhat troubled when I look at the proposed agenda … above all, I think with the terms of reference ‘the hazards arising from the continuous development of nuclear weapons’ prejudges where the greatest hazards lie.”

To which Russell, somewhat nonplussed, replies, “I can’t think that you would deny that there are hazards associated with the continued development of nuclear weapons.”

AB: There was a lot of reticence about joining this international movement of scientists — it was one of the first tentative measures to try and get détente through the back door, involving contact between the scientists of East and West. While Oppenheimer’s politics made him an obvious candidate to be approached by Russell, he’d been tarred and feathered with the “Communist” brush already and had lost his security clearance as a result. There were compelling reasons, perhaps, for him to be wary. Nevertheless, there were definite points of intersection between him and what became known as the Pugwash movement — after the site of the first meeting, in Canada — so Russell’s confusion is not surprising.

NG: Charitably, I think Oppenheimer faced, perhaps more acutely than anyone in the history of the world, the standard dilemma of whether, if you want change, you work within the system and try and reform it from there, or whether you wash your hands of it, let things go to hell and oppose it from the outside. This is the dilemma as the insider — he couldn’t be as independent, even in thought, as Russell could be.

That seems to be a fundamental difference between them.

AB: They were both public figures, but they were quite different. Russell liked to influence from the outside, and Oppenheimer, in some ways, became the consummate insider.

Oppenheimer was an institution builder — of the theoretical physics lab at Berkeley, for example, and most famously of the Manhattan Project. Russell, on the other hand, was an influencer — he influenced a school of philosophy, after all, among so many other things. But the way he exercised that influence was much more informal. Russell voluntarily gave up the life of a traditional don at Cambridge, whereas most of Oppenheimer’s career was spent in the academy and as a government scientist.

For much of his life, Russell was a dissenter, and when he wasn’t, he appeared rather uncomfortable with his “Establishment” associations. Also, the public aspect of his life wasn’t closely related to the primary area of his intellectual expertise, which were mathematical logic and philosophy. The political commitments happened after establishing that formidable intellectual reputation. With Oppenheimer, though, most of what he did seems to stem from his training as a physicist and scientist.

And yet Russell is sympathetic to him, and to other scientists. He seems to understand the dilemma of the insider, but also the tug-of-war between scientific exploration and political necessity.

AB: They were both grappling with ideas concerning the philosophy of science – is the disinterested pursuit of science and scientific knowledge always good, for example?

Russell captures this in a review for Brighter Than a Thousand Suns The Moral and Political History of the Atomic Scientists, written in 1958 by Robert Jungk.

Russell writes: “They had all adopted, unquestioningly, the scientific faith that knowledge is good and should be pursued without regard to practical consequences. Rather suddenly, their theoretical work was found to be of profound importance in the game of power politics for which nothing in their previous thinking or study had fitted them.

Temptations, some morally respectable and others not, assailed them. Some had to choose between serving their country and serving mankind. Others saw before them a career of influence and public applause if they served masters who did not understand what was at issue, but obloquy and disgrace if they remembered what politicians wished forgotten.

What happened was reminiscent of Faust, but on a global scale. Mephistopheles, often in the guise of an angel, led the scientists on, step by step, until their discoveries brought mankind to the brink of extinction.”

This is the dilemma that Oppenheimer, amongst others, found himself in, and that dilemma became increasingly tragic. At a time when the choice seemed to be an Allied bomb or a Nazi bomb, it was not such a difficult choice to make, but in the post-war world, the dilemma became more acute.

Joseph Rotblat, for many years Secretary-General of the Pugwash, personally resolved this dilemma, even before the first atomic bomb test at Los Alamos, by resigning from the Manhattan Project in 1944 after it became clear that Germany was not going to develop an atomic bomb. Rotblat was serving mankind. Oppenheimer was serving his country.

Are there any lessons from this period in history that are relevant to today?

KB: This nuclear nightmare recurs constantly – there may have been some periods when we’ve been able to relax from it, but it comes back. Almost every day now, there’s some statement from a Russian official saying, “Well, we could go nuclear…”

I lived in a nuclear-free world for two years, but it won’t be long before nobody will be able to say that.

A video just came to light a few days ago that illustrates why Russell was so impelled to fight the threat of nuclear war. In it, he says, “I can’t bear the thought of many hundreds of millions of people dying in agony only and solely because the rulers of the world are stupid and wicked. I can’t bear it.” And thus he took action. He was an atheist, and he didn’t believe in objective morality, but he was driven to action.

AB: Publicity about Oppenheimer and the early history of the atomic bomb is always salutary. Until now, when the issue is suddenly back on the agenda as a result of the conflict in Ukraine, there’s a sense that the large numbers of nuclear weapons all over the world, principally belonging to old superpowers, have been forgotten.

Whether by reading Russell — including some of his more apocalyptic statements about the existential threats to humanity — or examining the life of Robert Oppenheimer and the history of the Manhattan Project, anything that provides a reminder of the awesome and terrible power of these weapons is useful.