Why some Vietnamese Americans support Donald Trump

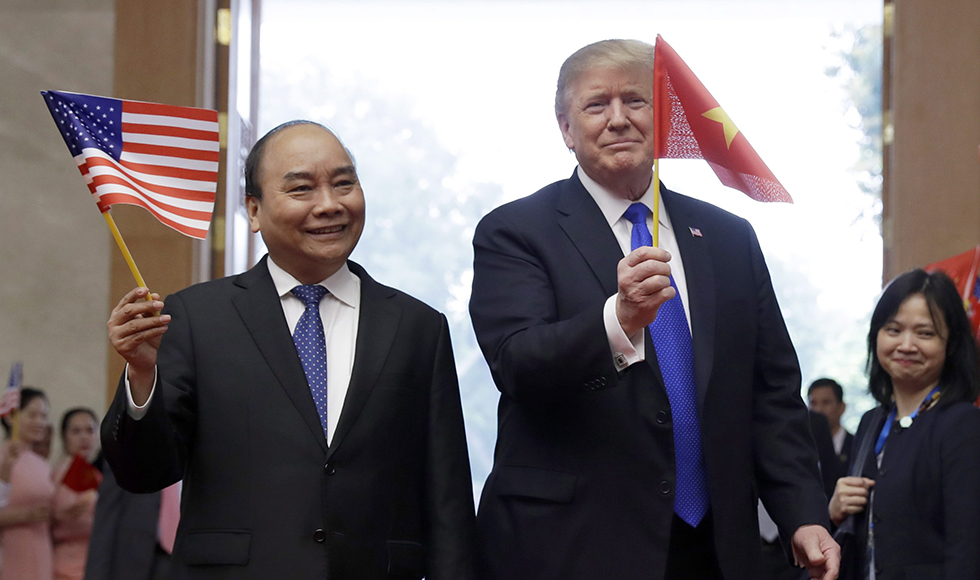

U.S. President Donald Trump waves a Vietnam flag as he meets with Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc, waving an American flag, in Hanoi in February 2019. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

BY Vic Satzewich, Professor of Sociology

August 20, 2020

Issues of race and racism are prominent in the United States as Americans prepare to vote in November.

Yet despite the racial unrest that has rocked the country for the past three months, U.S. President Donald Trump finds support among some racialized communities, including Vietnamese Americans.

In a recent informal poll carried out by a journalist of Vietnamese origin on Facebook, 94 per cent of her respondents said they’d vote for Trump in November.

And a recent video shows Vietnamese Americans on their way to the White House to announce their support for Trump.

Why?

Are these Vietnamese Americans planning to vote on the basis of domestic issues related to their multi-faceted experiences in the United States, on issues related to their homeland or what some have called “diaspora politics?”

As academics who study diasporas, my co-author and I believe we need to take a brief look at history to understand these issues.

History of colonization

Vietnam has a history of colonization and domination at the hands of the Chinese, the French and the Americans. They have met these efforts to usurp their independence with forbearance and resistance, but the path has often been difficult.

This is especially so in 2020, when Vietnam is facing an existential threat as a result of China’s effort to assert its dominance over the region, including in Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Read more:

How the push to unite South-East Asia against Chinese expansionism could backfire

In the West, the Vietnam War is well-known and has been widely documented. But among many Vietnamese, the term Vietnam War is a something of a misnomer; they see the war as something that was brought to them by the Americans.

But long before the American occupation and earlier French colonialism, Vietnam was under Chinese rule for over 1,000 years, from 111 BCE to 938.

The country became reunified in 1975 after North Vietnamese Communist forces drove out the Americans. There was a brief but bloody border war with China in 1979 when it attempted to invade and control Vietnam.

(AP Photo/Hau Dinh)

Vietnam has been able to reconcile itself with America and France, but when it comes to China there is a deep sense of distrust. This feeling has been exacerbated in recent years by China’s ongoing attempt to gain control of portions of the South China Sea.

These territorial and maritime claims are significant not only for their natural resources, but they also provide China with secure passage for trade and the movement of its naval forces. For the past several years, both Vietnamese inside the country and those living abroad have been protesting against the Vietnamese government’s Special Economic Zones law, which is seen as a vehicle for China to exert further influence in the country.

Exodus of Vietnamese

After the war ended in 1975, a mass exodus of Vietnamese escaped Communist Vietnam by boats in search of freedom. Between 1975 and 1997, more than 1.6 million Vietnamese resettled abroad, with the U.S. accepting the largest number of refugees during this wave.

(AP Photo/Peter O’Loughlin)

Today the total population of the Vietnamese global diaspora is estimated to be around 4.5 million.

Out of that number, about 1.3 million Vietnamese live in the U.S. The actual number, however, might be around two million when accounting for people who identify themselves as mixed race.

Even though Trump has often sung the praises of Chinese President Xi Jinping, the relationship between the White House and China has been anything but friendly.

The Trump administration renegotiated trade agreements and placed tariffs on Chinese imports. Other penalties and sanctions have also been levied after China passed a new security law on Hong Kong.

Last month, the U.S also strongly denounced China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea and argued such claims were unlawful. And now, Trump has signed an executive order that gives Chinese social media app TikTok until the middle of September to find an American buyer, or be banned from the country.

Read more:

Trump’s attempts to ban TikTok and other Chinese tech undermine global democracy

No fans of communism

Like Ukrainians and other Eastern Europeans who left their homelands during the Second World War and built lives elsewhere, the Vietnamese diaspora is no fan of communism.

As such, they have an ambivalent relationship with the current Communist government of Vietnam. They love their homeland, but not necessarily its government.

For those who are part of the Vietnamese diaspora in the United States, support for Trump is driven not just by his anti-socialist rhetoric, but also by the hope and perception that he will continue to stand up to China, and that this will indirectly protect Vietnam.

In the larger national context, the voting preferences of the Vietnamese might not seem very consequential, but if we consider that some live in battleground states, their votes could make a difference.

The Vietnamese diaspora, particularly those who were part of the first wave of immigration to the United States, may believe that Trump’s China policies serve their interests in the homeland. But focusing on this issue alone means they ignore other troubling aspects of the president’s domestic and foreign policy agendas.

Anna Vu, an independent scholar in Montréal, co-authored this article.![]()

Vic Satzewich, Professor of Sociology, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.