AMR and coronavirus variants: These researchers spot new threats to global health

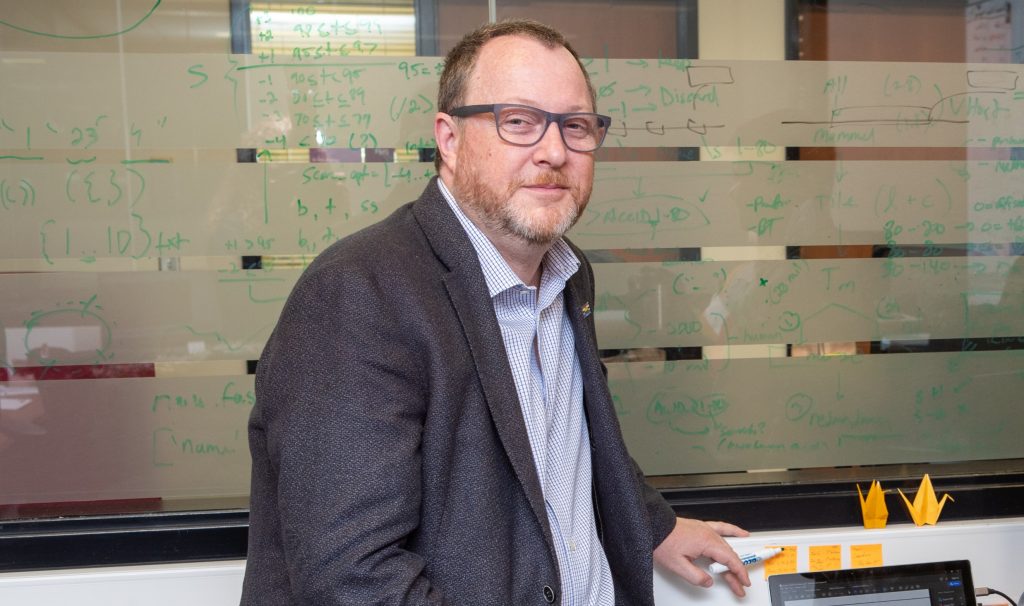

Andrew McArthur, a leading expert on genome sequencing, runs a lab dedicated to genomic surveillance of infectious pathogens. He is on the front lines of variant detection, creating computer models and software to gather data on COVID-19 variants. (Photo by Georgia Kirkos, McMaster University)

BY Michelle Donovan

March 3, 2021

Every four minutes of every day, supercomputers at McMaster collect new data and help public health agencies from all over the world, adding to a repository of information that has become a large global database for genomic mapping of anti-microbial resistance (AMR) and more recently, a crucial resource to identify and track COVID-19 variants.

Andrew McArthur, a leading expert on genome sequencing who runs a lab dedicated to genomic surveillance of infectious pathogens, is on the front lines of variant detection, creating computer models and software to gather data on new and possibly more infectious variants like those from the UK, South Africa and Brazil, and to be alert for those that have yet to emerge, sharing the information with the Public Health Agency of Canada.

“We will see more variants,” says McArthur, an associate professor in the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, a part of Canada’s Global Nexus for Pandemics and Biological Threats.

“We’re in a race. Mass vaccination will work, but between now and that time, we could have a really bad third wave if we’re not careful.”

Since November, when the pandemic’s second wave firmly took hold, McArthur’s lab has been gathering samples and sequencing them in partnership with Dr. Michael Surette of McMaster’s Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute to determine which variants were in circulation.

Together, they co-lead McMaster’s COVID-19 genetic testing and tracking efforts, partnering with many frontline clinical centres, Public Health Ontario, and Ontario’s COVID-19 Genomics Rapid Response Coalition.

Before that, he was part of the team from McMaster, Sunnybrook Hospital and the University of Toronto which sequenced virus samples from the very first patients in Ontario and isolated live SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

McArthur’s threat and surveillance lab’s core mission is to study antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which happens when infections caused by bacteria, parasites, viruses or fungi stop responding to medicines. Researchers at the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research call AMR a slow-moving pandemic which could be far more catastrophic than COVID-19.

“In conversations about coronavirus, we hear a lot of metaphors like we’re at war against coronavirus, and my constant reply is, ‘Welcome to my world,’” says McArthur.

“We work on AMR, which is worse in the long term. This pandemic is horrible, but we’re going to win this one. The mortality rate is horrible, but what concerns me more is AMR and what is going to happen after the pandemic.”

It is difficult science, he says, but by gathering data, creating software, and sequencing an infection to predict how it might behave, researchers can provide information so clinicians, physicians and public health officials can make the best decisions for patient outcomes.

McArthur compares his research work to his grandfather’s work as a code breaker in the Second World War.

“His job was to sit in a hut in the Pacific trying to identify Imperial Japan radio transmissions. If he picked them up, he would decode them and then he had to decide what to do about that information,” he says. “We do the same thing with infectious disease, but instead of a radio, we use genomics.”