Analysis: Controlling monkeypox: The time for Canada to act is now

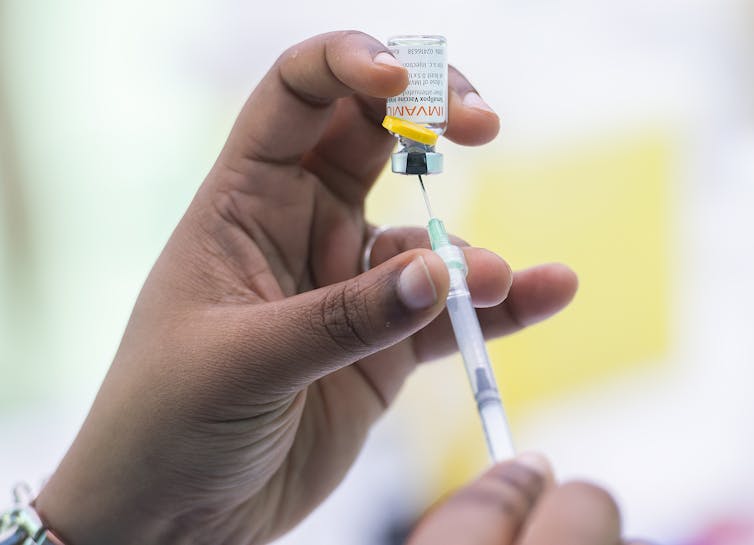

A health-care provider administers monkeypox vaccine at an outdoor walk-in clinic in Montréal, on July 23, 2022. It is crucial that people who have been exposed to monkeypox get vaccinated if they do not yet have symptoms, or isolate if they do have symptoms. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graham Hughes

BY Kevin Woodward

July 25, 2022

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared monkeypox a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. It’s likely that until about two months ago, many Canadians had not even heard of this disease.

Since May, monkeypox has been in the news everywhere, including Canada, where the number of infections has reached 681 as of July 22. It has started spreading from major cities such as Toronto and Montréal into regional centres such as Hamilton, where the first case was publicly reported July 4.

The good news is this: monkeypox is still quite isolated relative to the total population. There is still time to knock it back, and there is already an effective vaccine available, though supplies are limited.

The bad news is that the window is short — a matter of weeks, not months — to vaccinate the most susceptible and to encourage and support self-isolation for those who have symptoms. After that, monkeypox may expand beyond our capacity to control it with the vaccine supply we now have available.

Spurring individuals and governments to act may be challenging, though, given the degree of COVID-19 fatigue that has set in and the erosion of trust in public health measures, including vaccines, due to misinformation.

Monkeypox

Monkeypox, a close relative of smallpox, first jumped to humans in 1958. It has become endemic to a group of countries in Central and West Africa, but had been of little interest in other places until it also became a threat in North America and Europe.

What we’re seeing right now in Canada is that monkeypox is primarily affecting men who have sex with men. It’s not yet time to advise everyone to rush out and get a vaccine, but it is certainly time to make sure that those who are in the most affected communities understand the risk of infection, recognize the symptoms and take steps to protect themselves and others.

Despite having so far affected mainly men in the 2SLGBTQ+ community, it is important to emphasize that monkeypox is not at all a “gay disease.” It is spread simply though close personal contact, which may or may not involve sexual contact.

Given its current pattern of emergence in the 2SLGBTQ+ community, we must use the hard-earned lessons from the appearance of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s not to repeat the stigmatizing errors of that time, which were not only shameful in a social sense, but also detrimental to public health.

Lessons from HIV

In the 1980s and ‘90s, many people were afraid to get tested because of the stigma attached to HIV, even within the health-care system itself. The world has progressed considerably since then, both in its attitude towards 2SLGBTQ+ people and in the broader understanding of infection.

Back then though, many people did not want to know their HIV status because of the stigma. We can’t let that happen with monkeypox, as 2SLGBTQ+ advocates have noted.

Monkeypox is not as easy to transmit as COVID-19, but the fact is that all of us are equally susceptible, and all of us need to be aware and to prioritize measures that will extinguish this threat before it grows. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has proven the value of vaccination and the need for infected people to self-isolate to prevent spread, and we can apply those lessons to the monkeypox outbreaks.

Monkeypox symptoms are very rarely life-threatening, and include fever, chills, fatigue and muscle pain, followed by a distinctive rash. They typically take about 10 days to emerge after exposure, but can happen anytime between five and 21 days. Infectiousness usually takes two to three weeks to subside after that. Infectiousness ends around the time the hallmark lesions of monkeypox finally scab over and recede.

During the window between exposure and the appearance of symptoms, there is a golden opportunity to stave off individual illness and halt the spread of infection overall by vaccinating exposed people as quickly as possible. In this way, we can build a wall around the outbreak.

Mobilizing resources

The HIV epidemic, tragic though it was, served to mobilize health resources for and by 2SLGBTQ+ communities, and today those existing networks are being activated to educate and assist those who are most at risk during this stage of the monkeypox outbreak.

The Gay Men’s Sexual Health Alliance, for example, is proving to be a valuable hub for current and helpful information about monkeypox prevention, detection and vaccination, including information about vaccine clinics.

It is vitally important that anyone who has had close contact with someone who has monkeypox come forward to be vaccinated if symptoms have not appeared, and to isolate if they do have symptoms.

Isolating oneself, as we learned from COVID-19, is neither easy nor practical for a great many people. It is important that governments in Canada expedite financial supports that allow people with monkeypox to stay home and limit the spread of infection.

We have seen in both HIV and COVID-19 what happens when we don’t act in time. We know how to limit and end this outbreak, and we must take action now.![]()

Kevin Woodward, Infectious Diseases Physician, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.