Canadian auto industry’s shift to electric: Q&A with expert Greig Mordue

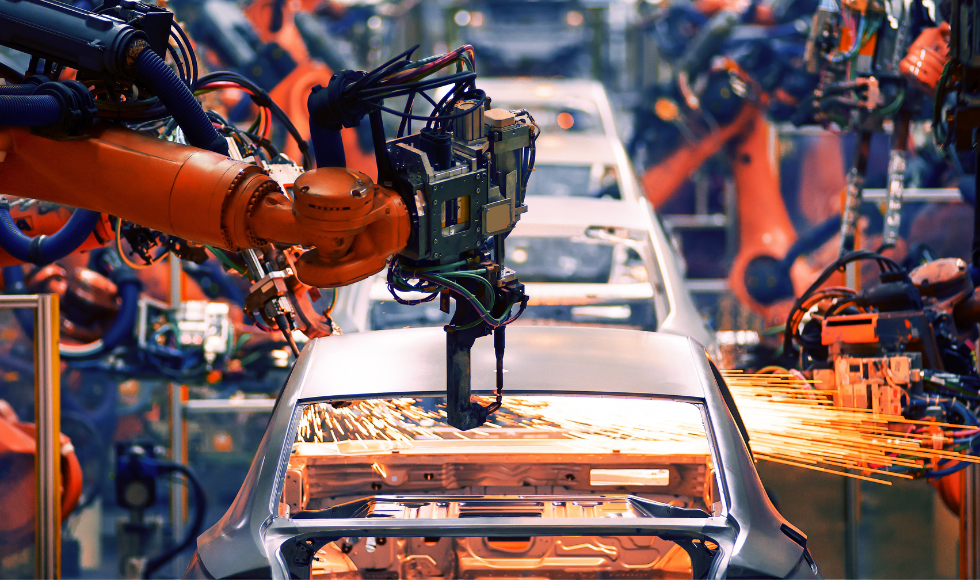

Manufacturing expert Greig Mordue talks about potentially rocky transition that lies ahead for Canada's automotive industry in light of ambitious electrification targets. (Shutterstock image)

January 12, 2023

In December, the first Canadian-made all-electric vehicle rolled off the line at a General Motors plant in Ingersoll, Ont. That plant had produced internal combustion engine vehicles for more than 30 years. The federal government also announced a plan for 20 per cent of all new vehicles in Canada to be electric by 2026. That target increases to 60 per cent by 2030, and all passenger vehicles sold in Canada are to be electric by 2035.

We talked to engineering associate professor Greig Mordue, the ArcelorMittal Chair in Advanced Manufacturing Policy at McMaster’s W Booth School of Engineering Practice and Technology, about the Canadian auto sector and the shift to electric.

How does the state of the Canadian automotive manufacturing industry look to you entering 2023?

I think we’ve had a couple of interesting years and there are some reasons to be relieved. However, I’m not sure that “optimistic” is the right description; perhaps “a little less pessimistic” is more apt.

We should not lose sight of the fact that since 2000, Canada has gone from producing 3 million vehicles per year to about 1.1 million. The investments we have witnessed over the past couple of years have been less about growing the industry and more about maintaining the status quo. That means we are unlikely to see a reversal of the trend we have experienced over the past two decades.

Most of the automaker-related investments that have occurred in Canada in recent years have been for model changes or refreshes.

Model changes happen in five- to seven-year increments. When a model change happens, assembly plants require major reinvestments for retooling, equipment and training, regardless of the underlying powertrain. That’s what we’re seeing now. The only difference is that some of the new models will be powered by batteries, not traditional internal combustion engines (or ICEs).

The federal government set targets for 20 per cent of new vehicles in Canada to be electric by 2026. How ready is Canada’s auto manufacturing industry for electrification?

Setting targets is the easy part. The problem is that those targets exist in an environment of significant fluctuation surrounding the market, technology, and supply chains. For that reason, it is possible that those targets might have to be modified.

Currently, the North American market is about 5 per cent electric. That means about 95 per cent of the market is for ICEs.

While it is difficult to challenge the net attributes of electrified mobility insofar as the environment is concerned, aggressive mandates for EVs in Canada and the U.S. should be a cause for concern, at least for the manufacturing portion of the industry in those countries.

Canadians in particular prefer lower-priced vehicles. Right now, electric vehicles are more expensive than internal combustion engine-powered vehicles — a lot more expensive. That means if North American manufacturers are unable to drive down the cost of EV production in sync with governments’ heightened EV mandates, the consequences could be severe.

First, automakers may have no choice but to shift production mandates even more rapidly out of high-cost locations like Canada to lower-cost places like Mexico, a process that has been happening since the implementation of NAFTA in 1994.

Second, if EV prices stay persistently high relative to ICEs, consumers may have no choice but to defer new vehicle purchases, further reducing demand and production in Canada’s automotive manufacturing sector.

Third, if policy makers insist on aggressive EV targets that North American manufacturers are unable to support, it is possible that manufacturers headquartered in China will be more than happy to step in. Beyond the availability of low-cost labour, Chinese firms also control most stages of the global battery supply chain.

What impact do you think electrification will have on labour in the auto sector?

It’s going to be a difficult, chaotic transition for both labour and communities.

First, the timing. It’s popular to assume that by gaining mandates to make EVs relatively early in the process, as Canada has done, our country is well-positioned going forward. Maybe. The problem is that some assembly plants might be retooled to build expensive EVs before the market is ready to embrace them.

Perhaps a more comfortable option — if options exist — is to ride the wave of ICE vehicles a bit longer and then transition production when the market is truly ready. Unfortunately, we don’t get to make those choices.

The GM CAMI plant in Ingersoll, Ont., is a good example. It was reopened by the prime minister and premier a few weeks ago. That plant used to have 3,000 people working there making the ICE-powered Chevrolet Equinox. The PM and premier were there to mark the plant’s switch to electric delivery vehicles. The problem is CAMI now has just 400 employees. it’s going to take a while for that plant to get back up to 3,000 workers, and it probably never will

Second, the nature of battery-powered vehicle assembly. Making EVs requires fewer people. An EV drivetrain contains about one-sixth the number of parts as an ICE and its assembly requires about 30 per cent less time. That means our assembly plants will need fewer people.

Third, the parts sector. No question, the transition to EVs is creating new opportunities. The LG battery plant in Windsor is the best example. Meanwhile, though, existing powertrain plants are unlikely to become battery plants. There are 64 such facilities in North America, including many in Ontario.

A Canadian-developed prototype electric vehicle, the EV Project Arrow, was unveiled at CES 2023 in Las Vegas. What’s the benefit of a project like that?

The benefit of the Arrow is its role as a marketing tool. It’s an elaborate calling card for the Canadian automotive parts industry to take around the world and show off their capabilities. The Government of Canada, the Province of Ontario and the Auto Parts Manufacturers Association put $8 million into this project. There were 58 companies involved and lots of them are small names in the automotive space that can use the Arrow to get attention from automakers.

Those involved in the Project Arrow process are unlikely to harbour illusions that their protype will ever reach production. While building a prototype is difficult, launching an auto company is prohibitively complex and expensive. Turkey, for example, has spent what I’d estimate to be more than $4 billion building an electric vehicle company and it’s unlikely many people have even heard about it.

The process of building an assembly plant and training workers, plus developing a supply chain, and a distribution, marketing and service system across dozens of countries is daunting. Then, the process must be repeated for multiple models.

There’s a reason why Canada hasn’t had a homegrown automaker since the McLaughlin Carriage Company was sold to General Motors 105 years ago. It’s hard.

That said, Project Arrow will help a lot of small companies gain access to customers and collaborators that might not have been possible. For $8 million it’s a relative bargain. By comparison, each of the largest automakers spends at least $1 million per hour on R&D 24 hours per day.